A while back I posted a poll on whether there'd be another global war. The top result was that there wouldn't be, but that there'd be smaller, regional wars between the great powers. With that said, what are some great power wars that you guys would find plausible over the latter half of the 20th Century? No global wars, but something more along the scale and duration of the Franco-Prussian or Crimean wars.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

English Canada/French Carolina: A Timeline

- Thread starter Gabingston

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 192 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 150: The World As Of 1970 World Map As Of 1970 Part 151: America Revisited - The Thirteen Colonies Part 152: America Revisited - The Great Lakes Part 152: America Revisited - The Great Plains Part 154: America Revisited - The West Coast Resource Guide: Commonwealth Of America Locations As Of Part 154 Russian Retcon Ideas (Could Be Contentious)

If I Ever Get Banned

I know I've stated this before, but I'm restating it so it can be threadmarked. If I am ever banned from this website, I will be continuing both this and my other TL on alternate-timelines.com. It is the only AH.com alternative that I am aware of, and I'm confident that I wouldn't be the only AH.com refugee on the website. I will copy/paste this into my other TL's thread.

Why would you get banned ?I know I've stated this before, but I'm restating it so it can be threadmarked. If I am ever banned from this website, I will be continuing both this and my other TL on alternate-timelines.com. It is the only AH.com alternative that I am aware of, and I'm confident that I wouldn't be the only AH.com refugee on the website. I will copy/paste this into my other TL's thread.

Stretch

Donor

There's also Sea Lion Press' forum, if you're interested.I know I've stated this before, but I'm restating it so it can be threadmarked. If I am ever banned from this website, I will be continuing both this and my other TL on alternate-timelines.com. It is the only AH.com alternative that I am aware of, and I'm confident that I wouldn't be the only AH.com refugee on the website. I will copy/paste this into my other TL's thread.

You know how my recent Italy update became the longest in the series at 2,700 words? Well, that record is going to be absolutely smashed by the Mitteleuropa update I'm working on, which has reached that amount of words and still has a ways to go. It'll likely be my first to pass the 3,000 word threshold. Expect it sometime next week (it'd usually be sooner than that, but I'm going on vacation this weekend and thus won't be working on the TL for a couple of days).

Part 145: Mitteleuropa 2.0

Part 145: Mitteleuropa 2.0

In June of 2020 I posted an update on Mitteleuropa, the German economic and political bloc that formed after the Second Global War. Soon after that update, though, I decided that I’d made it a bit too OP, and while I didn’t touch it for a while, I eventually retconned it. Well, now I am going to touch on the German bloc in Central Europe once again. Through their military and industrial might, the Germans had managed to beat both the French and Russians to become the dominant power(s) in continental Europe. I’ve done Mid 20th Century updates on the French, Russians and the Anglo-Americans, so it’s about time I do an update on Germany (Neuseeland notwithstanding).To start this, I’ll talk about the three smallest of the German states, those being Alsace-Lorraine, Rhineland and Switzerland. The first two of these states owed their existence to the Global Wars, while the last of them had been an independent country all along. Rhineland was split off from Bavaria after the first war., while A-L was split off from France after the first. Both of these states occupied the left bank of the Rhine, as did their capitals, Straßburg and Mainz respectively. Apart from the capitals, there were other major cities in each country like Mülhausen, Metz and Diedenhofen in A-L and Koblenz, Luxemburg, Trier and Ludwigshafen in Rhineland. Alsace-Lorraine and Rhineland were both majority Catholic with large Protestant minorities, though religious tensions were kept low by both states having freedom of religion.

The bigger issue for A-L was the sizable French minority that had developed during the time it’d been part of that country. Many Francophones moved across the border into France after the war, and those that stayed behind feared reprisals from the German majority. Said reprisals did indeed come, an example being the government forbidding French from being the primary language for education, even in majority Francophone locales. This led to a mixture of further emigration to France and majority Francophone border towns demanding to rejoin France, demands that were denied. The Rhineland didn’t have those same linguistic issues, with nearly their entire population either speaking Standard German or various Germanic dialects that weren’t too dissimilar from the standard.

Economically speaking, both A-L and Rhineland were more industrially powerful than you’d think for countries of their size. For example, the Mosel River basin, which stretched through both countries, had sizable mineral deposits, notably of coal. Combine that with the industrious culture of the Germanic countries and you got a highly industrialized and productive economy. I’ll get more into German industrial might later on, but for now it’s time to head south along the Rhine into Europe’s mountainous haven of neutrality, that being Switzerland.

Switzerland originated in the Middle Ages as the Swiss Confederacy, a decentralized organization of small Cantons. While the country had expanded and evolved over time, it’d kept its loose structure up until the present. It was probably needed to keep the country together, as despite its small size, Switzerland was a multiethnic country. While most of the country was German, the western cantons were majority French, while the canton of Ticino was majority Italian. In addition, there were also the Romansh of the high Alps, meaning there were four main ethnic groups within the country. In an era of nationalism, which was often based on ethnicity and language, keeping this pluralistic hodgepodge of a country together would usually be a tall order, and, yet, they were able to do it. Not only that, but Switzerland would go on to become an incredibly prosperous country, with Switzerland placing within the top five globally in terms of standard of living. Diplomatically, Switzerland practiced armed neutrality, not taking sides in conflicts but still maintaining a strong military in case someone did attack them. The Swiss stayed neutral in both global wars, avoiding the devastation that they wrought in the rest of the continent. After the war, the Swiss joined neither Mitteleuropa nor the Latin Bloc, so if there were a third war, they’d remain an island of peace in a sea of chaos.

Next, I’m going to talk about the non-German members of Mitteleuropa. Mitteleuropa, the economic and diplomatic bloc formed by the twin German powers of Prussia and Austro-Bavaria, comprised a large portion of Central Europe, uniting the core of the continent into a single market. This could be a mutually beneficial arrangement for both the two German powers, who’d gain political control over their surroundings and shield themselves from the Russians, and for the member states, who’d get German investment and the ability to move to the German states for education and/or employment. With the German states’ population growth slowing down as the demographic transition proceeded, they’d begin to draw upon their member states for labor, as they were earlier into said transition than the Germans were. By 1970 several million migrants (most of them being Slavic) resided in the German states, with Poles (whether from Poland proper or Polish Carpathia) alone comprising two million, in addition to the sizable Polish population born within the country (who were a majority in some border regions). In the member states, investment from the Germans flowed in, and while there was obviously already industry in these countries, industrialization took an extra leap forward as German companies opened new facilities in the east. Manufacturing was noticeably cheaper in Debrecen than in Düsseldorf or Białystok than in Bonn. With this influx of investment, living standards in East-Central Europe rose markedly between 1950 and 1970, and while it still lagged behind Western Europe, that gap was becoming narrower and narrower. Many non-German Mitteleuropans spoke German as a second language, and that number was even higher among the young, for whom German was a required subject in school to at least some extent. While they weren’t in the tier of London, Paris or Berlin, cities like Budapest, Prague and Warsaw became sizable tourist destinations, as they were every bit as beautiful and historic as their more famous counterparts. Outside of the big cities, the Carpathians grew in popularity as a destination for skiing and recreation, whether for locals or for skiers looking for something more off the beaten path than the establish resorts in the Alps, Pyrenees or Scandes. The cities of Krakow and Lemberg even began discussing possible Winter Olympic bids in the future.

Now that I’ve talked a good deal about the non-German member states, I think now’s an ideal time to get onto the big boys of the union, those being Prussia and Austro-Bavaria. I’ll start with the junior partner of the two, that being Austro-Bavaria, before moving north to Prussia.

Austro-Bavaria or Austria-Bavaria, officially the United Kingdoms of Austria and Bavaria, was formed after the First Global War as a way to strengthen each of their kingdoms against a possible Prussian threat. However, the policy of the Prussians was instead to reconcile with the newly formed state and invite them to join an economic and political union, even offering to put the union’s seat in the Bavarian city of Regensburg, the former capital of the Holy Roman Empire, as the founders of Mitteleuropa viewed their new union as a successor to the HRE. While Austria and especially Bavaria were still salty over the defeat in the war and the loss of regions like the Rhineland and Franconia (something I’m very strongly considering tweaking in a future Maps & Graphics adaptation, BTW), this did sound like a good enough deal, so they accepted the olive branch and joined into the new Prussian-led union of Mitteleuropa. Austria and Bavaria combined, however, were strong enough to effectively become the Cal Naughton Jr. to Prussia’s Ricky Bobby (please comment if you got the reference). This was only solidified by the joint effort between Prussia and Austro-Bavaria in the Second Global War, which put any remaining resentment Austro-Bavarians had towards Prussia firmly in the past.

As for some of Austro-Bavaria’s domestic politics, the new state would have an interesting structure. You see, the monarchs of Austria and Bavaria would remain as monarchs of their respective constituent countries, but neither would be the head of state of the country on whole. That would instead be the Chancellor of the new united Austro-Bavarian parliament, which would be based in Salzburg as a geographic and political compromise between Vienna and Munich (closer in distance to Munich but located in Austria, albeit along the Bavarian border). Below the two constituent states of Austria and Bavaria would be the provinces, which would act as administrative divisions both within the two states and at a national level. Under that would be smaller divisions like counties and towns/villages. In addition, Austro-Bavaria also possessed a colony in Northwest Africa, though I went over that in Part 123, so go there for more information.

Economically, Austro-Bavaria was a strong power in Central Europe. The western part of the country along or near the Rhine was the most industrialized part of the country, with cities like Stuttgart, Mannheim, Karlsruhe and Darmstadt being major industrial centers. With that said, pretty much every Austro-Bavarian city had some sort of industry. Many Austro-Bavarian cities became known for some sort of specialty that set them apart from the others. Salzburg was the political center, Vienna the cultural capital, Innsbruck the ski resort city, Triest the coastal resort city, Munich the place you’d go to get drunk in October, etc. While the living standard may not have been quite as high as in neighboring Switzerland, Austro-Bavaria was still by and large a pleasant place to live.

When it comes to demographics, Austro-Bavaria had a sizable non-German population, most notably in the south of the country. There resided the Slovenes, who made up the majority in the region of Carniola and a sizable minority in neighboring Carinthia. The Austro-Bavarian government had pursued a policy of Germanization towards the Slovenes, varying in intensity depending on who was administering it but always pushing for their assimilation. This had been an ongoing process in Carinthia for centuries, as Slovene had slowly but surely lost ground to German, and with official state backing of the latter, this process accelerated in that region. In Carinola, though, Slovene was more entrenched, as the whole region aside from some pockets of German was majority Slovene. Even here, Germanization proceeded throughout the 20th Century, particularly in urban areas like Laibach and Marburg. With German being a required subject in school (if not the official language of schooling), pretty much every Slovene who’d received formal education (I.E. pretty much anyone except for the elderly) spoke at least some German, though most still spoke Slovene at home. In addition, a sizable number of ethnic Germans had moved into Carinola, further Germanizing the region. With the majority of the Slovene population being bilingual, the Austro-Bavarian government figured that they’d done enough to Germanize the region, and with Slovene nationalism becoming more and more common, the province of Carinola decided to make Slovene a co-official language with German.

Outside of the Slovenes, the Austrian Littoral also had large populations of Italians (speaking various Italian dialects, most notably Friulian) and Illyrian Slavs (mainly Croats). Triest in particular was a multiethnic city, with Italians, Slavs and Germans all living in close proximity to one another. Triest, though, along with other Adriatic cities like Pola and Pflaum were favorite destinations for Germans looking to enjoy the warm and sunny (by Central European standards) climate, along with the beautiful Mediterranean scenery. As a result, the amount of Germanophones surged in the Littoral over the course of the 20th Century, both from migration and language shift among the locals. The Austrian Riviera became one of the most famous and luxurious tourist regions in all of Europe, particularly in the German-speaking countries.

Overall, Austro-Bavaria made an outsized impression on the world stage. Things like lederhosen, schnitzels and beautiful alpine scenery became popular images and stereotypes not just of Austro-Bavaria, but of the German states in general. However, in spite of this update now being over 2,000 words, we’re not quite done yet, as we’ve still got the big daddy of the German states left to cover, that being Prussia.

We’ve finally arrived at the last part of this update, and while I can’t say that it’ll be the best, it could very well wind up being the biggest (or at least the size of the Austro-Bavarian segment). Having been divided into small states for ages, the Kingdom of Prussia gradually unified the northern half of Germany over the 18th and 19th centuries. This was in large part due to the immense military prowess of the Prussians, who became known for having an incredibly effective army, to the point where the country became known as “An Army With A State”. While they initially had competition with the Austrians, the First Global War secured Prussia’s status as the masters of Germany, as well as one of the great powers. Not only that, but the Prussians expanded overseas, becoming a sizable colonial power in spite of their late start, particularly in the South Pacific, though they handed over the administration of the South Pacific colonies to the now independent Neuseeland. Meanwhile, at home, Prussia was possibly Europe’s most powerful country, with the French and Russians having been defeated and the British more focused on other matters than the continent. As the leaders of Mitteleuropa, Prussia got the benefit of control of land stretching from frozen Tallinn to balmy Triest. With such a vast swath of land, and their resources, under their control, Prussia’s economy thrived during the mid 20th Century. With the exception of the economic crisis of the late 1920s and early 1930s, Prussia’s economy experienced consistent growth, with only a few small recessions sprinkled throughout. The Rhine-Ruhr region was one of the largest and most productive industrial regions in the world, the only real competitors being North-Central England and the American Great Lakes. From Bonn in the south to Dortmund in the north, the boomerang-shaped corridor housed countless factories churning out massive amounts of industrial products. When combined with other industrial regions of Prussia like Silesia and Upper Saxony, Prussia was one of the largest industrial powers in the world. It wasn’t just in the quantity of industrial output that Prussia succeeded, though, as their culture of efficiency that came from their prestigious military bled over into their industrial sector as well. Prussian industrial products became known internationally for their quality, with Prussian industrial companies expanding globally. Much of this expansion, as talked about earlier, was within Mitteleuropa, which saw a boom of industrialization during the middle of the 20th Century. Industry already existed in the non-German Mitteleuropa states, an example being the mines and mills around the Carpathian capital of Ostrava, but with the common market industry exploded in East-Central Europe. The huge diaspora of Poles, Hungarians and other nationalities in the German States only helped this process, as workers who’d moved to the German states to work in the industrial sector could now move back home and aid in their own country’s industrialization. This process would continue beyond the scope of this update, which goes up to 1970, but by that year industry in the east was booming.

Speaking of diaspora, let’s talk about Prussia’s demographics, shall we?

Prussia’s population in 1970 numbered 80 million, one of the most populous countries in Europe. The largest city in the country was Berlin, the nation’s capital. One of Europe’s largest and most famous cities, nearly 10% of the country’s population lived in the Berlin metropolitan area, with the previously separate cities and towns of Potsdam, Oranienburg and Bernau now functioning as suburbs of the capital, connected via the vast public transit network and by high-capacity roads for carriages. Berlin Berlin was not the largest metro area in Prussia, though, as the previously talked about Rhine-Ruhr metroplex had a population of nearly 10 million, spread out between the seven or so major cities of the region plus the suburbs filling in the space between the city centers. Apart from Berlin and the Rhine-Ruhr, other major Prussian cities included the financial center of Frankfurt, the port cities of Hamburg and Danzig, the industrial cities of Leipzig and Dresden and the old Prussian capital of Königsberg, among others that I don’t have the time to mention.

With such a wide array of major cities, the Prussians would need fast and effective ways to connect them all. Enter two radical infrastructure projects that Prussia would pursue during the mid 20th Century. First was a series of high-capacity, high-speed intercity roads. With the rapid increase in the number of autocarriages (reminder: TTL's name for automobiles) after the Second Global War, the existing paved roads no longer sufficed for intercity auto travel. Thus, the Schnellbahn was born. These roads could carry multiple lanes of traffic in each direction without stopping, with ramps and bridges used to connect to the normal road network. The first segment was completed in 1929, connecting Potsdam to the western Berlin neighborhood of Charlottenburg (they'd originally planned to go right to the center of the city, but the citizens of the city didn't take kindly to it, so that plan was scrapped). Over the following years more segments were built around the Berlin area, and by 1940 a high-speed ring road around the city had been completed.

It wasn’t just in Berlin that Schnellbahn roads were being constructed, though, as roads to and within different cities were also being built. For example, the Rhine-Ruhr Schnellbahn was constructed during the 1930s, connecting all seven of the major cities. The Schnellbahn in the Rhine-Ruhr and in Berlin were also connected to each other by the mid 1940s, cutting travel times between Prussia’s two largest metro areas significantly. Soon the Schnellbahn system was being expanded to connect other Prussian cities, and by the middle of the 1960s Schnellbahn highways criss-crossed the entire country. Other countries would soon follow in building high-speed road networks (some of them having been thought up independently of Prussia), including the other Mitteleuropa states, whose networks were connected to that of Prussia, furthering the integration of the region.

It wasn’t just automotive transport in which the Prussians excelled, though, as the Prussians would enact innovative upgrades to their rail network. For decades tests had been conducted by countries ranging from the Commonwealth of America to France to Japan to create as fast of a train as possible. However, it would be the Prussians that would take the leap in creating an actual, operational high-speed rail line open to passenger traffic. In 1966, the Prussian government announced that they would upgrade the rail line between Berlin and the Rhine-Ruhr, the country’s busiest, into a high-speed line, with trains traveling at speeds up to 250km/h (155mph). Construction began the following year, and in 1971, the Berlin-Dortmund High Speed Rail Line officially opened, with stops in Hamm, Bielefeld, Hanover, Brunswick, Magdeburg and Potsdam. More lines would be built in both Prussia and the rest of Mitteleuropa over the following years, and other countries would soon develop high-speed rail lines of their own, but between the Schnellbahn and high-speed rail, Prussia would become known for having some of the world’s best transportation.

50 years after its foundation in the wake of the Second Global War, Mitteleuropa had become possibly the world’s most well-integrated and cohesive geopolitical blocs, and has inspired both the French and the Russians to found their own blocs. So far things were looking good in the heart of Europe, but a storm was brewing on the horizon. Would the so far 50 year peace in (most of) Europe be maintained, or would things go south as we headed into the latter part of the 20th Century? Only time will tell.

Member States of Mitteleuropa

- Prussia (Capital: Berlin)

- Austro-Bavaria (Capital: Salzburg)

- Rhineland (Capital: Mainz)

- Alsace-Lorraine (Capital: Straßburg)

- Hungary (Capital: Budapest)

- Carpathia (Capital: Ostrava)

- Ruthenia (Capital: Lemberg)

- Poland (Capital: Warsaw)

- Baltia (Capital: Riga)

- Estonia (Capital: Tallinn)

My next update will be on La Floride. Note that I will be retconning some previously stated things about the country, such as in the demographics (less full Afro-Floridians and more mixed) and possibly the political structre (Anglo-style provinces replaced with something similar to OTL's French Departments), though it won't be primarily political in nature. Just thought I should let you guys know, I know that I've been retconning a lot of stuff lately.

EDIT: I've decided to split the update in two due to its large size, which could've easily surpassed the giant German update. Demographics will come first, followed by culture.

EDIT: I've decided to split the update in two due to its large size, which could've easily surpassed the giant German update. Demographics will come first, followed by culture.

Last edited:

Part 146: Floridian Demographics in the Mid 20th Century

Part 146: Floridian Demographics in the Mid 20th Century

The French colony turned country in Southeastern North America, La Floride, has been a main focus of this series in its nearly five year (dang does time fly) runtime (I mean, it is the “French Carolina” part of the title). I have done numerous updates on this country over the years, whether it be the growing French colony in the earlier days or the independent country later on. However, these updates have been mainly political in nature, as I don’t recall making an update focused on the culture of this interesting melting pot of a nation. That changes today, as in this update, I will cover the demographics of La Floride through the middle of the 20th Century. What better place to start an update about Floridian demographics and than with the language the people there speak? With it having been over 300 years since the French began settling in the region, Floridian French had plenty of time to both diverge from the standard back home and preserve older features that were lost in the motherland. Most of the French settlers to La Floride came from the Atlantic-facing regions of the country from Picardy in the north to Gascony in the south, so while later immigrants from France came from all regions of the country, Floridian French drew its primary influences from dialects spoken in the north and west. Floridian French was also influenced to a lesser degree by non-French immigrants and settlers, particularly from Italy (especially in major cities like Richelieu, which had a very large Italian population). As mentioned a few sentences ago, Floridian French held onto some older features of French that had disappeared in the standard European variety. For example, the rolled R sound found in Spanish and Italian was also originally found in French, but shifted in Parisian French into a guttural, throaty R sound beginning in the 18th Century. While the guttural R became the standard in European French (though many in France, particularly native Occitan speakers, still used the rolled R), the rolled R retained its use in Floridian French, though some in the upper class, particularly in Richelieu, adopted a guttural R to sound more European (think some alternate Francophone version of the Transatlantic Accent). Another older feature of French that was lost in Europe but retained in North America was the pronunciation of the “oi” sound in words like “moi” and “toi”. While in France these had shifted towards “mwa” and “twa”, Floridian French kept the older pronunciation of “mway” and “tway”. Floridian dialects also varied by region, class and ethnicity as well. For example, the accents of the Atlantic coast and Gulf coast were noticeably different due to being separate settlements during the colonial era, along with urban dialects specific to Richelieu and New Orleans. Afro-Floridians also possessed their own patterns of speech separate from their White counterparts, ranging from standard French with an accent on one end to the creole language of Floridian Patois (think OTL’s Louisiana Creole) on the other, with several varieties in between. There’s obviously a lot more to Floridian French than just this, but I’ll leave it here, as I am neither a linguist nor am I fluent in French (or any foreign language, for that matter, I’m your typical monolingual Anglo).

Now that I’ve talked about the language, I supposed I should talk about the people who speak it. Floridians came from a variety of backgrounds, from the descendents of the early French settlers to more recent immigrants to Afro-Floridians descended from those who’d been brought over against their will to the Amerindians whose ancestors had been there all along. The majority of Floridians, about 65% to be exact, were White Floridians of full or mainly European descent. Being the primary ethnic group in the country, White Floridians were found pretty much everywhere, with their population ranging from a large, dominant minority in some areas to almost 100% of the population in others. The largest chunk of European ancestry in La Floride unsurprisingly came from France, as almost all White Floridians had some degree of French heritage, most of them a strong majority. Even in the Mid 20th Century hundreds of thousands of French immigrants lived in La Floride, and many more had French parents and/or grandparents. While many more groups would add their own flavors to Floridian culture, the base would remain undeniably Gallic in nature. After that were the Italians. While Italians had been present in La Floride since the early colonial era, Italian settlement really only took off after the First Global War, with the peak of Italian immigration occurring between 1880 and 1910, as well a secondary peak in the 1920s. After the 1920s Italian immigration tapered off, and the second and third generation rapidly assimilated into Floridian culture, intermarrying with the native-born population at extremely high rates while leaving their impact on Floridian culture, particularly in cuisine (more on that in the next update). After the Italians it was a sizable drop to smaller White immigrant groups, as over 80% of European immigrants to La Floride through 1950 had been French or Italian. This 15-20% of immigrants were mainly from other parts of Catholic Europe like Poland, Germany, Ireland and Spain, as well as Catholic Arabs. There were also a small number of non-Catholic European immigrants, whether they be Protestant, Eastern Orthodox or Jewish (Floridian Jews numbered about 100,000 in 1970, 40% of them in Richelieu). The overall White Floridian population grew from 27.67 million in 1950 to 31.98 million in 1960 and 36.18 million in 1970, still growing steadily but with the year-to-year rate on a slow decline.

After that came Afro-Floridians, the descendants of those taken in chains to the Floridian colony. In spite of La Floride representing a small fraction of the total Atlantic Slave Trade, the lower mortality rate among Floridian slaves when compared with their Caribbean counterparts led to La Floride having one of the largest Black populations in the Americas. Afro-Floridians made up about 20% of the total population, or about 12 million people. The concentration of Afro-Floridians varied widely depending on what part of the country you were in. While some areas like the Appalachians and West were under 5% Black, others like the Îles du Mer (well, those that weren’t being swallowed up by the burgeoning Richelieu metroplex) and Mississippi Bottomlands were majority Afro-Floridian. Having been brought to the country in captivity to grow cash crops, Afro-Floridians were for a long time a mostly rural population, with urban areas being more associated with European immigrants. This was beginning to change, as with the mechanization of agriculture Afro-Floridians began to look for jobs in urban areas. Afro-Floridians, being poor and looked down upon by most Whites (and also many mixed-race Creoles, more on them later), were often concentrated in the least desirable areas of major cities, often poorly and shoddily built shantytowns. Correspondingly, Afro-Floridians often had the worst jobs, such as low-end service work. It’s worth mentioning, though, that not all Afro-Floridians were poor and marginalized, as some had become quite well-off and respected in spite of their skin color and cultural differences. The status of Afro-Floridians was beginning to become a hotly debated topic within Floridian society, and is definitely a subject for another time, so I’ll get back to that some time in the future.

While 20% of the population was Black, about 30% of the population had some sort of visible African origins. The other 10% of that equation (about 5.5 million people) were the Floridian Creoles, a mixed-race ethnic group of African, European and occasionally Amerindian origin. Emerging out of the plaçage system of colonial times, less pleasant means from the colonial era or more recent interracial marriages between Whites and Blacks (legal but often taboo), Floridian Creoles served as a middle caste between the White elite and Afro-Floridians. Creoles often owned land or businesses, and could sometimes become as or more successful than the common Petit Blanc White Floridian, which became a source of tension between the two populations. Even then, marriages between Creoles and Whites did occur (and were less taboo than White-Black marriages), and many Creoles emphasized the European aspect of their heritage over their African one, though this was by no means universal. Past marriages between Whites and Creoles meant that a good number of White Floridians had some small degree of African admixture, not enough to be outwardly noticeable but enough to become family lore and later appear in DNA studies once those become a thing further down the line.

The final 5% of the population, or about 2.75 million people, were of a variety of different origins. The largest were Florida’s indigenous population, whether in the form of tribal populations like the Mascoqui, Salagui, Tchactas and Chicachas or the Métis, which technically referred to those of mixed European and Amerindian ancestry but had also become a cultural label for Amerindians who’d assimilated into mainstream Floridian culture, regardless of their admixture. Between the tribes and the Métis, the Indigenous population in La Floride numbered about 1.75 million in 1970, not as large as in countries like Mexico or Peru but still a noticeable minority. In addition, due to the high rate of intermarriage with and assimilation into the general Floridian population (especially for the Métis and for those who lived outside of the reservations), many Floridians who weren’t identified as Indigenous or Métis nonetheless had small amounts of Amerindian ancestry, though not large enough to be visible.

The next largest share of this last 5% were the other type of Indians, those from the Subcontinent, specifically the former French colony in Southern India. After the abolition of slavery in the late 19th Century, some Floridian planters seeked to replace Afro-Floridian slavery with Indian indentured servitude, as had been done in the Caribbean by both the British and French. While this plan didn’t ever come to full fruition, it did lead to the establishment of a surprisingly large Indo-Floridian population. Most of the Indo-Floridians were Catholics, as Catholics were favored by the authorities, but a sizable minority were Hindu, making Hinduism the third largest religion in La Floride (just a tad smaller than Judaism in second). A second wave of Indians came to La Floride after the independence of the Deccan, mainly Catholics and Franco-Indians fearing reprisals from the Hindu majority. Between the earlier arrivals and the newcomers, the total Indo-Floridian population in 1970 numbered around 400,000, with 70% being Christian, 20% Hindu and 10% belonging to other faiths, mainly Islam and Sikhism. Richelieu was home to the largest Indian population in the country, with the Petite-Inde neighborhood being home to 60,000 Indo-Floridians, or 1/5th of their population.

Due to the long border and economic ties between La Floride and Hispanic America (mainly Mexico), a good sized Hispanic population had developed in La Floride, primarily along the Mexican border. While many of these blended into the general White Floridian population, about 300,000 Hispanics didn’t fit into any preexisting subgroup in the country. These were mainly Mestizos or Amerindians who nonetheless weren’t identified with the native Indigenous or Métis populations. Still, due to the common Latin Catholic roots of both nations, assimilating Hispanic immigrants wasn’t generally a huge problem for La Floride (nor was it for Mexico assimilating the smaller but still present Floridian population on their side of the border). The Chinese numbered about 100,000 in La Floride, making them the largest East Asian population in the country. While some had been brought over as fieldhands for a similar reason to the aforementioned Indians (particularly for rice cultivation), many Chinese wound up settling in major cities. For example, the Quartier Chinois in Richelieu had a population of 35,000, or over one third of the total Sino-Floridian population, complete with all the sights and attractions you’d expect from a Chinatown neighborhood. They’d mainly come from the south of the country, leaving from the port of Guangzhouwan, which had been a French trading port before the Second Global War. The remaining 250,000 people came from populations ranging from Muslim Arabs to non-Chinese East Asians, but they’re not large enough of a demographic to be worth discussing in detail.

Between all the different ethnic groups I’ve discussed, the overall population of La Floride in 1970 was 56.25 million, growing from 42.56 million twenty years prior. This made it one of the most populous countries in the Americas, behind the Commonwealth and Brazil and roughly equal with Mexico. Richelieu, the country’s once political and still cultural and economic capital remained the largest city, growing to a population of a tad under five million people by 1970, continuing to grow outwards into the woodlands, swamps and islands surrounding the city. Obcau, for example, had been mostly rural fifty years prior, but now was a densely populated urban area with roughly half a million residents, and this was a process repeated elsewhere throughout the urban area. The political capital of Villeroyale had overtaken New Orleans to become the second largest city in the country, growing to a population of 2.3 Million by 1970. The capital had grown to the point where it and the nearby city of Fort Toulouse had begun to merge, a process that would continue throughout the remainder of the 20th Century. Combine that with the relatively close city of Bienville, and a greater urban area was beginning to form along the central part of the Alibamons River, though once again that’d be a long-term process. New Orleans hung on in third place at 1.8 million, with its growth hampered by both a lack of adequate buildable land and a severe hurricane in the late 1960s (as IOTL). Three more Floridian cities had joined the one million club since 1950, those being Saint-Hyacinthe at 1.3 million, Ville-Marie at 1.1 million and Jolliet at 1.025 million, with several others coming close. 75% of the population lived east of the Mississippi River, due to its earlier settlement and greater utility for agriculture, though the area west of the Mississippi was now growing at a greater rate due to migration both internally and from neighboring Mexico. In addition, the Great Floridian Peninsula (or La Grande Péninsule in French) began to attract retirees from the Commonwealth, who came during the winter months to escape the cold. Tourists from the Commonwealth could stay for up to three months at a time, so it’d be common for retirees to leave at or just after Christmas and return just before Easter, missing the coldest months of the year. Speaking of that, I think now is the perfect time to talk about something I haven’t with regards to La Floride, that being emigration.

While Florida had always been a net immigration recipient, there were also a good number of Floridians who’d emigrated for better opportunities elsewhere. By far the largest emigration destination for Floridians was the giant to the north, the Commonwealth of America. Having a much higher standard of living than their own country, Floridians had been moving up north for decades, seeking better paying work and a brighter future. In 1970 about 1.25 million Floridian immigrants lived in the Commonwealth of America, largely in regions closer to the border and with a milder climate than, say, Laurentia. Floridian neighborhoods popped up in Commonwealth cities like Baltimore, Norfolk, Philadelphia, St. Louis, Losantiville (which I’m considering renaming), Rapidston (which I’m also considering renaming) and, of course, New York. The Little Florida neighborhood in Queens was the largest concentration of Floridians in the Commonwealth, with nearly 100,000 Floridians living in that one area. In addition, the border regions, especially those that had been annexed by the Commonwealth after the First Global War, had sizable Francophone populations, with the Acansa province being 15% French-speaking, largely descended from settlers who’d arrived before the annexation by the Commonwealth.

The second largest destination for Floridian emigrés was, to no one’s surprise, France. Wealthy Floridians had long traveled to France for education and to make connections with the European elite. With France’s economic golden age during the mid 20th Century, though, migration from Florida to France began to become more and more common among the general population, though many of them were French emigrants returning to their homeland. The number of native-born Floridians in France in 1970 was 150,000, of which 1/3rd lived in Paris and another 1/4 in the French Riviera, the warmest and sunniest part of France that felt a little bit like home for Floridian emigrants. 100,000 Floridians lived across the border in Mexico, which while less than the amount of Mexicans in Florida did prove that migration between the two countries was a two way street.

One more thing worth touching on here is religion. As with the rest of Latin America (which I’m counting Florida as part of), the country was mostly Catholic, with 88% of Floridians identifying as Catholics as of 1970, 45% of those being weekly or more mass attendees. Six percent of Floridians were Protestant, most of them being converts to American-style low churches, while one percent were members of other Christian sects (mainly Eastern Orthodox), adding up to a 95% Christian population in 1970. Four percent of the population were secularists who didn’t identify with any religion, with their beliefs ranging from a vague deism to full-on atheism (insert comment about fedoras here). Finally, one percent of the population followed non-Christian religions, which I talked about earlier and thus don’t feel a need to repeat.

Alright, I think that just about wraps this update up. I was originally going to do one update that covered both the demographics and culture of La Floride, but as it got long and longer I figured that splitting it up was a necessity. Meanwhile, this update passes the 3,000 word milestone on the number 3,000, which was something I couldn’t pass up. My updates are getting longer and longer, and while I’m not sure whether it’s due to me becoming a better writer or merely becoming better at using more words to say the same amount, it’ll sure help me if I ever have to write a college essay. The next update will primarily cover Floridian culture, as well as some other things that tie into it. That should be done by the end of the month, after which I’ll move onto other things both here and possibly in UOTTC. Until then, though, I must bid you guys adieu.

definitely this would be the culturally richest country in the world.

I imagine that from the 1970s there would be a large flow of Muslim immigrants from North Africa and the Near East, just as it was in France in our timeline, possibly by 2023 they would be more than 5% of the population.

I imagine that from the 1970s there would be a large flow of Muslim immigrants from North Africa and the Near East, just as it was in France in our timeline, possibly by 2023 they would be more than 5% of the population.

Well, the title for the world's culturally richest country certainly isn't uncontested, but La Floride would certainly hold its own in that regard.definitely this would be the culturally richest country in the world.

I imagine that from the 1970s there would be a large flow of Muslim immigrants from North Africa and the Near East, just as it was in France in our timeline, possibly by 2023 they would be more than 5% of the population.

As for Islamic immigration, one thing to consider is that the Scramble For Africa doesn't happen to nearly the same extent as IOTL. France only held the coastal parts of Algeria ITTL, and lost it after the Second Global War save for a few port cities. Thus, North Africa has much less French influence than IOTL. Combine that with the general attitude in Western Europe likely being more opposed to non-western immigration than IOTL (remember, there are no Nazis or Nazi equivalents ITTL), and I doubt that France would have that large of a Muslim population ITTL. This goes even more so for La Floride, as they are isolated from North Africa by a whole ocean rather than a mere sea.

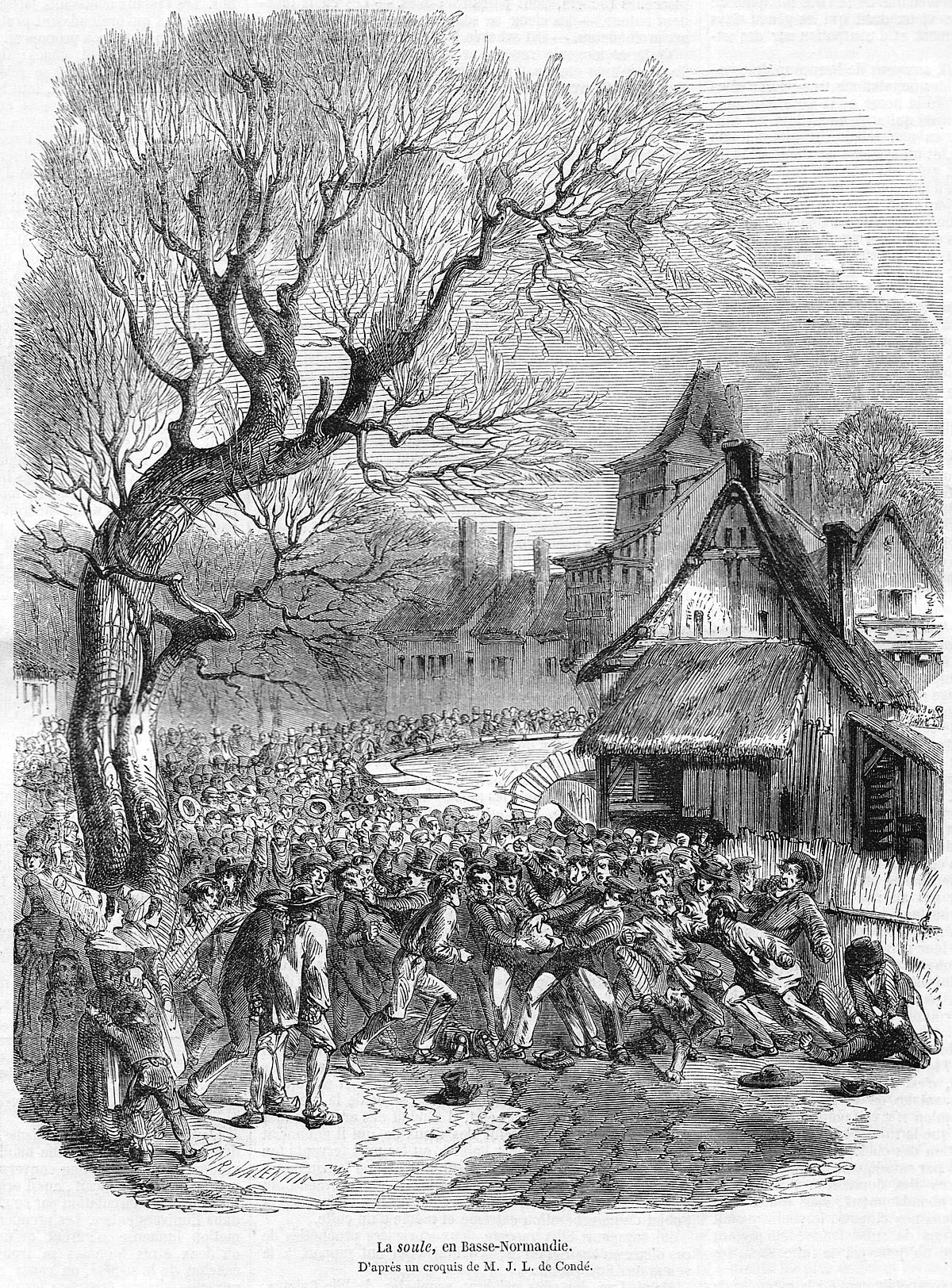

I know this is from two and a half years ago, but I'm writing an update on Floridian culture that involves sports. This would be a really interesting idea for a sport popular in La Floride (and in France itself). It'd be pretty plausible, too, considering the Norman and Picard origins of many of the Floridian colonists. I'd have to think about how the game could/would evolve if it went from a folk game to a standardized, codified sport. Judging from the Wikipedia page you could move the ball with your hands, feet or a stick, so it could end up having elements of football, rugby, lacrosse, field hockey and hurling among other things. We could do a private convo if you'd like.Perhaps the French in Florida would see the development of their own national sports as well. Perhaps a version of La Soule?

La soule - Wikipedia

en.wikipedia.org

Sure man, hit me up!I know this is from two and a half years ago, but I'm writing an update on Floridian culture that involves sports. This would be a really interesting idea for a sport popular in La Floride (and in France itself). It'd be pretty plausible, too, considering the Norman and Picard origins of many of the Floridian colonists. I'd have to think about how the game could/would evolve if it went from a folk game to a standardized, codified sport. Judging from the Wikipedia page you could move the ball with your hands, feet or a stick, so it could end up having elements of football, rugby, lacrosse, field hockey and hurling among other things. We could do a private convo if you'd like.

I agree that this would easily be one of the culturally richest countries in the world, hands down. Of course that might not directly translate into being politically rich, especially if only whites (and mixed-races people) and/or Catholics can vote in Florida.

Part 147: Floridian Culture Through the Mid 20th Century

Part 147: Floridian Culture Through the Mid 20th Century

For the second half of the Floridian update, I’ll now talk about the culture of the country up through 1970. I’ll have to get moving on into the latter part of the 20th Century at some point, but I just wanna get everything caught up first. While it wasn’t by any means the premier cultural power in the world, La Floride did pack a good punch in terms of cultural influence. From its French base, Floridian culture came to include non-French European (particularly Italian), African, Amerindian and even Asian influences. I feel like it’s about time to get into the nitty gritty of one of the most interesting countries in the Americas, so let’s start with something that a French-descended country would inevitably be known for, food.With its mother country being a culinary juggernaut, La Floride already had a head start in becoming a cuisine powerhouse on its own. The French colonists in colonial-era Florida brought their own culinary traditions from their particular regions, which would mix and merge into the basis for Petit Blanc cuisine. The cuisine of La Floride would receive a massive amount of African influence due to the presence of the Atlantic Slave Trade in the colonial era, with the African captives bringing over their own culinary practices. Africans, even when in chains, would make a remarkable contribution towards the development of Floridian cuisine. Add in the influence of Indigenous food practices, and you get the formation of Floridian cuisine. The mixed-race Floridian Creoles in particular became famous for their cuisine, as their blend of cultural backgrounds showed through their food. This cultural blend was shown off famously through La Floride's soups and stews, which became some of the country's most famous culinary offerings. Gumbo, Jambalaya and Étouffée (all OTL Louisiana dishes, I know) were not only common dishes domestically, but also spread internationally via the Floridian emigrés from the last update. These dishes notably all contained bell peppers, celery and onions, which were a very popular combination among Floridian cooks and chefs, to the point where they got the nickname of the Holy Trinity.

Outside of soups and stews, there were still a variety of Floridian foods to talk about. One of these examples was the variety of pork products consumed in the country. With the woodlands that covered the eastern 2/3rds of the country being ideal conditions to raise pigs (in addition to a large feral pig population), pork was the most popular meat in the country. For example, Sausage, while most associated with Central Europe, was also a common offering in France, and that carried over to La Floride. Sausage varieties like boudin and andouille were widespread in La Floride, as they were in France, and other, more local sausages were also produced. Pork also served as the centerpiece of boucheries, where entire extended families would gather and eat a whole pig (sometimes a young piglet), along with other foods.

Other common ingredients in Floridian cuisine were various grains (particularly corn and rice), seafood (fish and crustaceans), other types of meat (beef and chicken especially), fruits (notably citrus), vegetables and a wide variety of cheeses (no s**t, Sherlock, of course a French-descended country loves cheese). Immigrants of course made a huge impact on Floridian cuisine too. The mass wave of Italian immigration led to various Italian foods becoming commonplace in Floridian cuisine, with Italian restaurants and groceries being commonplace across the country. The same was true for other immigrant groups, as Hispanic, Arab, German, Polish and Indian cuisine all had a decent presence in La Floride, moreso in the areas where those groups settled. With all of this added up, La Floride was one of the most culinarily rich countries in the world, and foodie tourists would unsurprisingly flock to the country in droves.

Since I’ve covered the eating part of Floridian cuisine, I might as well get to the other side of the coin and talk about their drinks. I’ll start off with the obvious beverage of choice for a Francophone country, that being wine. With the French being notorious for their love of Le Vin, it was no wonder that the first vines were planted soon after the colony was founded. However, the hot and humid climate was not conducive to the growing of old world Vinifera grapes, as diseases were commonplace and harvests were subpar. Not to worry, though, as La Floride had a variety of indigenous grape species, some of which were already being consumed by the natives. Early on the French began to experiment with using these species for wine, and it didn’t take all that long for the colony to begin producing its own wine with native grape species, with the Petit-Blancs in particular consuming a lot of homegrown wine (the Grand-Blancs preferred French imports). Floridian viticulturalists also began to experiment with hybridizing old and new world grape species, and while it took a good deal of trial and error, hybrid grapes eventually became commonplace in La Floride (and even in Europe once new world grape diseases crossed the pond).

In the mid 20th Century La Floride was one of the 10 largest wine producing countries, the majority of their production being of hybrids. Though production took place nationwide, regions like the Piedmont and Caquinampo Valley became known for their viticulture, as the milder climate made it easier for hybrids or even straight-ahead Vinifera to grow, and also made the landscape in these areas all the more pretty. Floridian hybrids also became utilized for viticulture in other parts of the world with similar climates, particularly Brazil. While wine critics may have favored more prestigious winemaking regions in the old world, Floridians were proud of their own viticultural tradition, and continued to consume their homegrown wines in large quantities.

However, that was not the only drink consumed by Floridians, as plenty of other beverages were commonplace. With a subtropical climate (full-on tropical in the far south) suitable for the growing of citrus (particularly along the gulf coast), citrus-based drinks were a common beverage in Florida, particularly in seaside resort towns. Another tropical drink common in La Floride was rum, as the country was a sizable sugar producer. While not super popular, Florida did produce beer, much of it linked to historical German, Irish and Polish immigration, all countries heavily associated with said drink (though Germany does produce a fair deal of wine as well). Floridian drinks were not just limited to alcoholic ones, as non-alcoholic beverages were also consumed to a large degree. Coffee and tea were the two most popular non-alcoholic beverages, with coffee being easily imported from the Caribbean and tea having been grown in La Floride since colonial times. Cafés and teahouses (oftentimes the same establishment) were widespread across the country, found in pretty much every Floridian town larger than a thousand people (and some that were smaller). Regular, unfermented fruit juice was commonly consumed as well, particularly by children or by members of Protestant sects that opposed alcohol consumption (though the latter often drank the aforementioned coffee and tea as well). Sweetened carbonated drinks, popular in the Commonwealth of America, had also begun to percolate down south, whether in the form of American businesses expanding or Floridians starting their own beverages.

Between food and drink, Floridian cuisine was world famous, and definitely one of the most notable parts of the country’s culture. However, that’s far from where it ends, as other aspects of Floridian culture were also worth talking about. For example, La Floride was also incredibly interesting artistically, particularly when it came to music. The same blend of European (primarily French), African and Amerindian influences that made Floridian cuisine so interesting also held true when it came to Floridian music. Richelieu and New Orleans were the major centers of Floridian music, with numerous cabarets, theaters and public spaces hosting musical performances, with smaller Floridian cities also playing host to music as well. European instrumentation mixed with African rhythm to create an entirely new sound that would come to be emblematic of the country (probably something similar to OTL’s Jazz). Other forms of music were also prevalent in La Floride, from the French-derived folk music of the Petit-Blancs to the African sounds of more isolated Afro-Floridian populations (in the Îles du Mer for example). As with the cuisine I talked about earlier, Floridian music gained an international audience, as Floridian musicians performed in and emigrated to France and the Commonwealth. While music was La Floride’s most notable artistic field, the country also had a notable presence in other areas. As an example, while France was easily the biggest player in the Francophone film industry, La Floride also had a sizable presence in film, between homegrown productions and French films being produced there. The far southern locations of Biscaine and Île Osseuse in particular became popular filming locations due to their tropical climate and scenery. The tropical scenery also became a popular location for painters, who you could see painting the sights and scenery in any number of Floridian coastal towns, as well as in the big cities. The center of the Floridian painting world was the Institut Floridien des Beaux-Arts, which among other things operated the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Richelieu, one of the largest art museums in the Americas and one of the top tourist attractions in the country.

Speaking of institutions of higher culture, let’s talk about that, shall we? It didn’t take too long for the first university in the Floridian colony to be established, that being the Seminaire de Richelieu in 1668, later renamed to the Université de Richelieu (or UdR for short). UdR, due to its early establishment and importance, also held the status as the most prestigious university in the country, becoming the Floridian equivalent to the Sorbonne (which had been the institution where Cardinal Richelieu taught). UdR was not the only prestigious university in La Floride, though, as the Université Royal in Beinville, despite being two centuries younger, was not too far behind in its importance. Most major Floridian cities had some sort of university or college, mostly operated by the government or the Catholic Church, though the vast majority of Floridians didn’t attend university at this point. Speaking of the Catholic Church, they were probably the most powerful cultural institution in the country. As mentioned in the previous update, nearly 90% of Floridians were Catholics, and the Church ran many institutions like schools and hospitals. Churches were often the centerpieces of their respective towns, and cathedrals were among the most iconic landmarks in the country (particularly Notre-Dame de Richelieu, due to it being in the largest city and being the seat of the Archbishop of Richelieu, the most influential clergyman in the country). Catholicism also shaped the culture of the country in other ways. For example, the Floridian Carnival, where Catholics would feast and party in the few days before Ash Wednesday (particularly on Mardi Gras, the final day of celebration), from where they’d have to give up meat and something else of importance until Holy Thursday a month and a half later. This had become a major public spectacle, with parades and celebrations being major annual events in major Floridian cities. The largest was unsurprisingly in Richelieu, where the Carnival would draw over a million attendees per year by 1970, both locals and tourists.

On the topic of activities, how about we get to the athletic scene in La Floride? Sports, as in any other country, were a very popular form of entertainment in La Floride, both in person and through viewing and listening. For example the Stade H.P. LeGrand in Villeroyale had a seating capacity of 80,000 spectators, one of the largest stadiums in the Western Hemisphere, and the Colisée Cardinal in Richelieu (specifically the suburb of Point Cardinal) wasn’t far behind at 75,000. Whenever La Floride would compete in international sporting competitions, millions would tune in on radio or the rapidly growing visual media (whatever TV would be called ITTL). Many different sports had some sort of audience in La Floride, both foreign and homegrown, and top athletes were among the most famous people in the country.

As in many other countries, the most popular sport was Association Football, or Piedballe as it was translated into French (I know the French call it football or Le Foot IOTL, but this is my TL and I can do what I want. TBH I’m kinda surprised the French didn’t translate the name IOTL, considering the French tendency towards linguistic purism). As with many regions, France had its own traditional games involving kicking a ball with one’s feet, and those traditions were carried over to their colony in North America. Meanwhile, the English codification of Football made it over to France soon after its creation, followed by the French taking it over to La Floride, where it soon became very popular. The Floridian Ligue de Pied was the most popular sports league in the country, with the championship match being listened to or viewed by millions each year. The Floridian national team wasn’t so bad either, with them making it as far as the quarterfinals in the Prix du Monde (in 1962 specifically). Batonball made its way south into La Floride from the Commonwealth of America, as American troops introduced it during the Global Wars. The first Floridian player in the American Batonball League (or ABL for short), Georges Gagnon, debuted in 1937 and played in America for 12 years, and more would soon follow. The most successful Floridian ABL player, Richard Duval, became known as “The Floridian Phantom” for his incredible speed and seemingly impossible plays in the field. La Floride also had its own Batonball league, the Ligue Baton de La Floride, but the ultimate goal of Floridian batonball players was to play in the Commonwealth. Rugball also made it to La Floride, both of the British and American varieties. Rugball teams often shared venues with football teams, due to the similar footprint of the two sports’ fields, and as with batonball, top Floridian rugball players often went to play in other, more prestigious leagues abroad. Individual sports like tennis, golf and boxing were also popular in La Floride, with tennis player Marcel Dupuis coming in second place at the 1952 Olympics in Madrid. Even sports you wouldn’t expect like skiing had an audience in La Floride, with La Floride having a dozen ski areas in 1970 in both the Appalachians and their small slice of the Rockies. Some of the notable ones included Mont des Hêtres and Val des Élans in the Appalachians and Feu des Anges and Pic de L’est outside of the town of La Veine in the Rockies. Moving away from physical sports for now, Auto Racing was also becoming popular in La Floride, with the top racing series in the world which I have yet to name (TTL’s F1 equivalent) hosting three races in the country between 1966 and 1968. More regional series like the North American Auto Tour (or NATT for short) also hosted races in La Floride on a more regular basis, though their main market was the Commonwealth of America. Local race tracks and leagues also operated their own races, drawing aspiring racers seeking to make it big.

You know I mentioned homegrown Floridian sports earlier on in the update? Well, I feel as though I should get to it now. In Northern and Western France, they had their own traditional sport known as La Soule (or La Choule depending on the dialect), in which teams would compete to get a ball to the other team’s goal, often a church, using their hands, feet or sticks. The French colonists, who were mostly from the North and West of France, brought over their athletic tradition to the colony. Upon arrival, they found that the natives to this land had their own ball games, using sticks to move the ball and attempt to score on the opposing team. The French colonists would incorporate influences from the Amerindian games into their own, creating an all new sport native to La Floride. Known as the Jeu de Poteau (or Post Game), or Le Poteau for short, this Floridian sport would be centered around two teams using sticks to hit a leather ball onto the opposing team’s goal post, scoring more points the higher on said post it was hit. The game had mostly been a folk game, sidelined in favor of more established sports from abroad, but over time it became more organized and codified. Teams and leagues began to pop up around the country, and finally, in 1968, the Ligue National du Poteau, or LNP was formed. There were of course other sports played in La Floride as well, but this update is running long, so I’m gonna call it here.

La Floride was by this point one of the most culturally vibrant and rich countries on the planet, with their food, art and customs becoming known worldwide. I might take a bit of time away from the website, as I think I’ve been spending too much time online and need to touch some grass. I will keep working on this and my other TL, though, so stay tuned. For now though, have a happy June.

I'm thinking of doing an update on the Philippines either for the next one or one of the ones after that. However, I doubt the British would've kept a name that originated with a Spanish monarch, so I'm trying to come up with alternate names for the archipelago. I generally have a butterfly net outside of The Americas until the French Revolution, which includes monarchs, so they could name it after King George III, who'd be the monarch when they acquire the islands from the Spanish (The Georgine Islands? Georgin(i)a? Georgia?), or they could give it some generic name like the British East Indies. If the alt-Philippines want a new name after independence, names I've thought of include Austronesia, Luzon(ia) , Insulindia and Nusantara or names from OTL like Indonesia or Malaysia (or Malaya). I'd like to hear from you guys if you have any ideas, though.

For me, position of Korean Empire in this Japanese-led alliance is interesting. How independent Korea is? Does the allianche even has a name? Are Japanese forces stationed in Korea? Probably Japanese and Korean ( not so happy about that? ) forces are stationed in Manchuria?

For the Philippines, I would go with either the British East Indies if the British are occupying more of the Southeast Asia region adjacent to the Philippines, or the Georgian Islands for the monarch who acquired the islands from Spain.

I'll be honest, I don't think Korea and Japan being allies was very well thought out, considering that tensions between the two nations goes back even further than the POD of this timeline. Asia in general may need a bit of a redo once I do the Maps & Graphics sequel.For me, position of Korean Empire in this Japanese-led alliance is interesting. How independent Korea is? Does the allianche even has a name? Are Japanese forces stationed in Korea? Probably Japanese and Korean ( not so happy about that? ) forces are stationed in Manchuria?

I'm almost done with the Philippine update, and spoiler alert, it's gonna be one of those two names.For the Philippines, I would go with either the British East Indies if the British are occupying more of the Southeast Asia region adjacent to the Philippines, or the Georgian Islands for the monarch who acquired the islands from Spain.

IMO, it isn't impossible, Japan just needs to avoid turning Korea into a colony. Establishing protectorate and later, after enough reforms and finding a suitable ruler for Korea (that will not work against Japan), they might give her "independence" again.

For the Philippines, I would go with either the British East Indies if the British are occupying more of the Southeast Asia region adjacent to the Philippines, or the Georgian Islands for the monarch who acquired the islands from Spain.

Yeah, Georgian Islands seems interesting.

Threadmarks

View all 192 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 150: The World As Of 1970 World Map As Of 1970 Part 151: America Revisited - The Thirteen Colonies Part 152: America Revisited - The Great Lakes Part 152: America Revisited - The Great Plains Part 154: America Revisited - The West Coast Resource Guide: Commonwealth Of America Locations As Of Part 154 Russian Retcon Ideas (Could Be Contentious)

Share: