Chapter 85: Luzon War Part II - Tomoyoshi Triumphs Again

Throughout September, reinforcements from Bireitō and Kyushu landed in Luson province. First to arrive were 5,000 from Bireitō commanded by Wakamatsu Hisahide (若松尚秀), the eldest son of Wakamatsu Tomohide. Following them was the Iriebashi squadron of the Azuchi navy as well as Tagawa Seikou’s private fleet of Chinese junks. From Kyushu, a vanguard army of 10,000 commanded by Tachibana Tanenaga would arrive at the end of the month, with more men in the process of getting mobilized by Shimazu Norihisa. A further 8,000 men would arrive in Awari in October from the Mōri domain in the home islands in addition to those levied from Mōri possessions in Luson province. The arrival of such reinforcements significantly boosted the military strength of the Japanese. However, the Spanish would also see a boost in their military strength as well in late October, with a fleet of 17 warships led by Diego de Egues y Beaumont bringing both naval and land reinforcements. The land reinforcements included professional Spanish soldiers much more effective and experienced than the native companies that made up most of the Spanish army in the Philippines, as formidable as the latter were. The participation of the reinforcements in the war would thus shape late 1660 to be a particularly intense affair.

Meanwhile, after the Battle of Pantabangan, Kanbe Tomozane had retreated to the southern Cagayan Valley to regroup and levy more men from the region. They were tailed by Filipino-Spanish bands who not only repeatedly harassed the Japanese but also attempted to organize a Lusonese uprising against the Japanese in the region. The latter, however, surprisingly went nowhere for the most part. Ever since the acquisition of northern Luzon by the Japanese, a new social hierarchy had developed in the region with the samurai taking over as the new ruling class atop the native population, and many Lusonese natives did resent their new overlords. Crucially, however, Japanese rule contrasted with the old Spanish-Catholic regime through its policy of general religious tolerance and relative hands-off approach towards many cultural traditions of the Lusonese, particularly that of the highland tribes. As a result, whatever issues the natives had with the Japanese ruling class could not match memories of Spanish oppression and forced conversion to Roman Catholicism. This made recruitment of the Cagayan natives to the Spanish cause nearly nonexistent, and efforts towards that distracted from further attacks upon the Japanese army. Tomozane’s army successfully retained enough strength and cohesion to return to Carig [1].

In mid October, Kanbe Tomoyoshi would leave Awari at the head of an army of 14,000, composed of his personal retinue and the reinforcements from Bireitō and Kyushu. He left his 12 year old Tomomoto (神戸朝基), who had recently undergone his manhood rites, in the provincial capital under the guardianship of Tsuda Nobutaka (津田信高). Shortly afterwards, the Mōri troops under the command Kikkawa Hiroyoshi (吉川広嘉) began to march westwards, hugging the Lusonese coast with the ultimate destination being Pangasinan. Within a month, Tomoyoshi’s force would coalesce with Tomozane’s men and from there would march southwards, determined to lay waste upon any Filipino-Spanish army between Carig and Manila. Meanwhile, the main Spanish army led by governor general Juan Manuel de la Pena Bonifaz continued to gather more levied native troops from across the Philippines and would also incorporate 4,000 Spanish professionals brought from Madrid by the fleet. This main force would subsequently enter the southern Cagayan Valley as well. Several of his subordinates urged caution when confronting the Japanese as compared to the Filipino-Spanish troops, the former were better trained and more experienced being a mostly samurai army and this made fighting a field engagement very risky. Pena Bonifaz, however, was confident and decided to ignore his subordinates’ advice, concluding that the Japanese field army was too big of a threat to simply be ignored.

The Spanish army thus marched northwards on the eastern banks of the Magat River, maintaining supply lines through control of the river. In response, Tomoyoshi sent native archers on canoes to sail downstream and harass the enemy and their provisions. This grew into such a problem that Pena Bonifaz was forced to move away from the river, eventually encamping along a tributary, the Caliat River. This was exactly what Tomoyoshi had hoped for. As the Spanish settled in, the Japanese general moved based on the intelligence gathered by spies and the archers and managed to surround the Spanish army on two sides, from the western river plain and the northern hills. The Japanese numbered 21,000, with Lusonese auxiliaries, Bireitoan samurai and auxiliaries, Tomoyoshi’s elite retinue, and the Ryuzōji clan atop the hill under the command of Tomoyoshi himself and Tomozane leading the rest of the force on the river plain along with all the Japanese cannons. Realizing the position he was in, Pena Bonifaz immediately prepared his men for battle, fortifying his position with cannons and wagons to his north and west. He had 19,000 men with him.

The hasty Spanish defenses only delayed the inevitable Japanese victory. Tomoyoshi would deploy his 1,000 Bireitoan and Lusonese archers first, having their projectiles arc over the cannoneers and wagons and hitting the infantry. While this was going on, a formation of musketeers and Bireitoan heavy tachi swordsmen came down from the hills and slowly approached the Spanish formation, stopping intermittently to fire their muskets. These men proved to have a more difficult time, as Pena Bonifaz deployed his artillery and companies against them but the latter’s ranks were weakening from the arrow fire. On the river plain, meanwhile, the battle had begun with barrages of cannonfire followed by a traditional field engagement. The decisive moment came when the samurai cavalry on the hilltop finally decided to dismount and jumped into the fighting as heavy infantry. This broke the Spanish infantry on the north and they began a hasty retreat. The Japanese would begin to stream into the encampment, isolating those fighting the Japanese to the west. When the enemy realized their predicament, their morale and discipline plummeted for the most part, the professional Spanish soldiers being the only ones to stand their ground, and they retreated only to be caught by the Japanese already in the encampment. By the evening, Pena Bonifaz had left the battlefield and half of the Spanish army lay dead or injured and abandoned to be captured and executed by the Japanese, whereas Tomoyoshi’s force suffered 2,000 casualties.The Spanish were forced to retreat out of the Cagayan Valley.

Salmon = Japanese, Yellow = Filipino-Spanish

A decisive battle also took place at sea between the Spanish and Japanese. Tagawa Seikou’s fleet sailed towards Manila on a mission to initiate a blockade upon the Philippine capital and conduct raids on the Visayas. On November 1st, his fleet of 34 ships met Beaumont’s Spanish-Philippine fleet of 27 ships at the Battle of the Dasol Bay. Whereas the entire Spanish fleet was entirely made up of European-style warships, 10 Chinese junks in the possession of Seikou himself composed part of the Japanese fleet, although these junks were specially outfitted with heavy guns. As a result, in terms of firepower, they were on par. Nevertheless, due to the greater mobility of the Japanese ships, Tagawa Seikou would achieve a minor victory, sinking 4 Spanish ships as opposed to losing only one of his own. However, it wasn’t enough to clear the way to Manila as the Spanish fleet sailed back to Manila damaged but in fighting shape. Seikou would subsequently request more naval support from the home islands.

Even with only a marginal victory in the seas, the Japanese had clearly retaken the upper hand in the Luzon War thanks to the leadership and experience of the great Kanbe Tomoyoshi. Because of the victory at the Caliat River, the Cagayan Valley would remain secure for the rest of the war and the Spanish would be thrown onto the defensive once again. Tomoyoshi’s competence and skills, attributes long noticed by the rest of the realm, however, would ultimately bring him away from the southern frontier of the Japanese realm and towards the fight for the heart, soul, and future of the Oda Chancellorate. In January 1661, this journey would begin when a merchant from Mikawa province reached him just before the general resumed his march upon Manila. The merchant, Chaya Nobumune (茶屋延宗), would hand Tomoyoshi a letter from Tokugawa Noriyasu containing shocking news about the situation in the home islands.

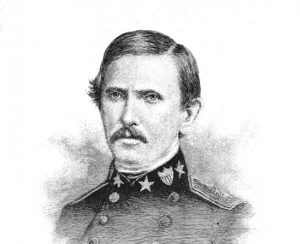

Portrait of an older Kanbe Tomoyoshi

[1]: The city of Santiago was renamed to its original native name of Carig.