True, but passion and emotion are vital components to a happy marriage i can See what Charles was dissapintedIt be like that sometimes. And Isabella isn't a very emotional person either.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Grand Duchy of the West - A Valois-Burgundian TL

- Thread starter BlueFlowwer

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 58 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 47 - England from 1523 to 1526 Chapter 48 - Brabant, France and England from 1525 to 1527 Chapter 49 - Spain and the Holy Roman Empire 1523 to 1525 Chapter 50 - Spain and the Holy Roman Empire from 1525 to 1526 Chapter 51 - Brabant, France and the Holy Roman Empire in 1527 Chapter 52 - Spain from 1527 to 1528 Chapter 53 – England in September of 1528 Chapter 54 - Brabant and France in 1528He's gonna be disappointed in that regard. Isabella prefers music and masses to passion and people. But on the other hand, Charles has grown up being educated about passionate love stories, so he's as lost as well.True, but passion and emotion are vital components to a happy marriage i can See what Charles was dissapinted

Last edited:

Let's hope their children can provide a bridgeHe's gonna be disappointed in that regard. Isabella prefers music and masses to passion and people.

Perhaps they will. Or perhaps they won't.Let's hope their children can provide a bridge

Fair enough, children can make things worst between couples sometimesPerhaps they will. Or perhaps they won't.

True that.Fair enough, children can make things worst between couples sometimes

Although i'm very happy that it has Made things better For the happy couples in the storyTrue that.

Yes it had. Speaking of happy couples, next chapter is in England, where we will meet another soon to be happy pair.Although i'm very happy that it has Made things better For the happy couples in the story

Well, that’s unfortunate. It probably doesn’t help matters that Charles grew up with his parents’ loving example, only to find himself in such a cold marriage. It could be worse, I guess?

It's not fun for him or Isabella.Well, that’s unfortunate. It probably doesn’t help matters that Charles grew up with his parents’ loving example, only to find himself in such a cold marriage. It could be worse, I guess?

Hopefully they’ll learn. The last bit of the chapter gives me hopeChapter 21 – France in 1500

Charles is not sure what to make of his bride. The new dauphine of France is a young woman, with a rich dowry and impeccable linage. Infanta Isabella of Portugal is tall, fair, and dark haired with dark grey eyes. She’s lovely enough to break any young man’s heart. Nothing in her behaviour is unseemly, as she carries herself with poise and dignity. She greets everyone in court with politeness and listens to small talk with an attentive ear. She dances gracefully with all who ask her during feastings and dines with moderation at the high table. His mother is pleased with her, and his father enjoys the dowry that came with her. His four-year-old sister Marie adores her. So does the commoners, who cheered on her when she entered Paris and later after coming out on the steps of Notre-Dame cathedral. Isabella, or Isabelle as she now goes by, is flawless as far as everyone is concerned in the kingdom.

Charles finds her cold. Isabelle is as lovely as the night stars, but to him she’s just as remote. She smiles at him at times, but it doesn’t reach her eyes. She talks to him at times, but there is no warmth in her voice. She accepts his small gifts and company, but he feels like he barely knows her. Their marriage had been consummated properly, but it had felt less like passionate experience, more clinical. Not like the stories he had read about during childhood. Sure, he boasts to his friends about “burying himself in the warm acres of Portugal” after his wedding night, but it’s a lie in a way. The virgin blood on the wedding sheets is the most he has gotten from his wife so far. Charles knows his first duty to Isabelle is to seed her womb with a prince and he hopes his wife conceives quickly. Perhaps a baby would melt the ice. At the least she can go to Chateau in Blois while the baby grows inside her.

View attachment 827485

Isabelle of Portugal, Dauphine of France

His mother counsels him to be kind to Isabelle, saying that a new land can take a long while to adjust to. To give her space and let things take their time. His father counsels him to be courteous and to visit her bed often. If he wants to indulge himself in passion, a mistress can be found in private. If he fathers a royal grandchild.

Charles sees the first glimmer of something other than glassy dignity five months after the marriage. An elaborate mass in the cathedral in Reims in early December seemed to move Isabelle in ways few things does. The music is beautiful, filling the whole cathedral with sounds. Charles watches her face light up when the winter sunlight filters through the multi-coloured rose window. For a moment there is a tear running down her pale cheek and Isabelle seems to exhale deeply, like letting something go from her chest. His gaze is transfixed upon her, so when her slim fingers drop to caress her lower stomach in a moment of unguarded relief, his whole world tilts completely of axis in a matter of seconds.

Suddenly Isabelle’s eyes find his own and for the first time his wife’s gaze is filled with something other then distance. It’s not warm exactly, but it something more than just coolness right now.

Author's Note: A rather short chapter here, but I neglected France in this tl since 1480. Ah, the complexities of an arranged marriages and two people who don't really know how to communicate with each others.

You gotta end things on a hopeful note sometimes.Hopefully they’ll learn. The last bit of the chapter gives me hope

I hope they will grow into friends, at least.It's not fun for him or Isabella.

I hope so too. Most Royal Marriages worked not because the pair fell in love with each other, but because they learned to form a partnership, to work together...I hope they will grow into friends, at least.

We will see what happens to them.I hope they will grow into friends, at least.

That is true also...I hope so too. Most Royal Marriages worked not because the pair fell in love with each other, but because they learned to form a partnership, to work together...

Chapter 22 - England in 1501

Happy Coronation Day! Have more celebrations in the english court!

Chapter 22 – England in 1501

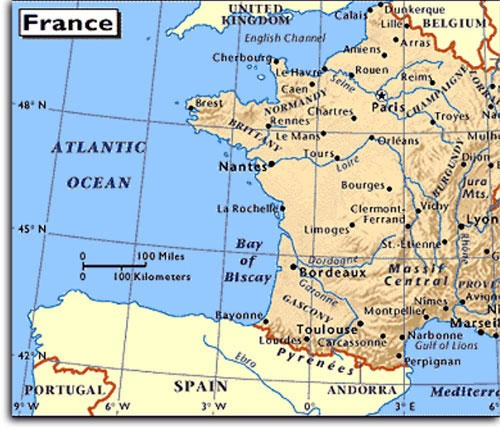

The voyage from the port of Ferrol in Galicia to Southampton in Hampshire was uneven for the seven ships departing after Easter in 1502. Atlantic winds did not bother the ships much, as they strived to avoid the temperamental Bay of Biscay. The English channel on the other hand, seemed to be in a bad mood when they rounded the duchy of Brittany as a storm seemed hellbent on making the last days sour for everyone onboard. The ships docked at Southampton in late evening, a little worse for wear. Days of rains had soured the mood of the crew, but in the hours before the afternoon the sun had broken through the cloudy sky, framing the small fleet seen across the horizon. Infanta Catalina of Castile and Aragon was able to get up on the damp deck and enjoy the warmth of spring as her new homeland was sighted in the distance. In her hands she clutched the saint medallions from Santiago de Compostela cathedral. Both had been purchased before the journey. Saint Brendan for a safe seafaring journey and Saint George for her new kingdom. The city of Ferrol where her ships left was also the starting point for the Camino Inglés or The English Way for those on the path of pilgrimage. Catalina would have seen plenty of english men and women at the time when she left from the cathedral to the port. Rumours had spread that the Princess of Wales to be would leave for her marriage and the pilgrims in the areas would be the first Englishmen to greet their future queen to be.

The journey of Infanta Catalina to England

The mayor of Hampshire would receive the Infanta and her retinue and their first night was spent in the castle of Southampton, where warm food and roaring fires awaited them. The old fortress had been renovated by King Richard several times and the Spaniards could relax for a few days in comfort while they got their land legs back. Messengers were already racing towards the King and Queen, and Prince Richard. The royal family were at the time close to Winchester Castle where the bride and groom would meet at last. Queen Beatrice knew that the Spanish rigid court etiquette prohibited an infanta from entertaining her future husband or father-in-law before marriage had been completed. And even more importantly, Beatrice knew that for her new daughter in law, coming to England from the Iberian kingdoms could be disorienting. Fortunately, it said nothing of mothers in law, so Beatrice took a splendid entourage with her as well as her eldest daughter, Bea to greet Catalina. The king and prince arrived in Winchester, where it was abuzz with preparations for several days.

The meeting between Queen and Princess was a very positive one. At the age of sixteen Catalina was a fair skinned girl with lustrous auburn hair, a round face and blue eyes. She was of average height but seemed taller with her posture. Prince Richard was not overly tall either, but would hit another growth spurt after the wedding. While he would never be as tall as his uncle Edward IV, he grew to be taller than his father.

Winchester had prepared a royal welcome for the new princess and when the royal entourage crossed the Westgate the city erupted in joy. Merchants had dressed in fine clothing, ladies their most colourful gowns, and hangings from the buildings showed both silks, tapestries, and cloth of gold and silver. The white rose of York decorated every corner and children threw flowers and herbs along the main road in front of the horses and carriages. The city aldermen meet the Queen and princesses on the steps of Winchester cathedral along with the bishop and churchmen. The splendour of the cathedral impressed the Spaniards along with the celebrations. For a daughter of Isabel the Catholic, the religious building must have been a great comfort and an opportunity to reflect on the past weeks.

It was here Catalina finally met the young man she had left Spain for, the purpose of her life since she was a toddler. Since the pair had already been married by proxy, the meeting was accepted by all partners. The Prince of Wales proved a sight for her seeking eyes. Richard was a young man of fifteen, with thick dark hair and grey eyes marked by heavy eyebrows. Still somewhat lanky, the english royal clothing padded him out somewhat, making him an impressive figure. The prince had dressed up for meeting his bride; cloth of gold and silk doublet, with a velvet overrobe trimmed with fur.

The royal party left Southampton to travel towards London after a few days, moving at a leisurely pace. Commoners gathered at the roads to catch a glimpse of the foreign princess, marvelling of her rich dresses in Spanish style and her entourage. The entry into London had been carefully planned. Catalina wore a splendid gown in cloth of gold and embroidered silk with an overrobe of crimson velvet lined with fur and her rich auburn hair hung down in glossy waves with a carnation-coloured cap on top. Her ladies had dressed in black to avoid outshining their princess and covered their hair with mantillas. Every Spaniard had been partnered with an english of the same status. Catalina rode a richly harnessed mule and was accompanied by Princess Beatrice, who wore cloth of silver and dark blue velvets. The papal legate rode next to her while the king’s heralds lead the way. Commoners perched themselves somewhat recklessly in windows, roofs, and other high places to observe the progression. The display of Castilian pride was high and while London was no stranger to Spaniards in the city, this went above and beyond. The reactions were somewhat mixed. The women in the entourage were seen as strange due to their black clothes and the future Lord Chancellor Thomas More, remarked in one of his few crueller moments, that some of her ladies seemed like “hunchbacked, undersized, barefoot pygmies from Ethiopia.” Later in life, More would become a loyal servant to the so-called pygmies’ princess and her York king.

Several pageants had been constructed around the city for the entry. They were colourful and filled by symbolism. Actors performed on the stages, dressed as saints. Lions, dragons, white roses and horses adorned them while the company wound their way towards Lambeth Palace, the residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. The mayor of London, dressed in crimson satin, guided them from the various pageants. Two dozen sheriffs and aldermen accompanied them in black and scarlet. The city itself showed its best face for the day. The buildings had been hung with tapestries and silks in bright colours. Musicians played various instruments and Catalina and Beatrice could enjoy the ballads performed for them. While Thomas More had dismissed the princess’s ladies, he had nothing but praise for the infanta herself. “Ah, but the lady! Take my word for it. She thrilled the hearts of everyone: she possesses all the qualities that make for beauty in a very charming young woman. Everywhere she receives the highest of praises; but even that is most inadequate. I do hope this highly published union will prove a happy omen for England.”

Richard, Prince of Wales and Infanta Catalina on their wedding day

The wedding took place in St Paul’s Cathedral. Edmund, Duke of York fourteen years old at the time, escorted her from Lambert Castle to the cathedral doors. The ceremony was simple and quick, but no less magnificent for it. The greatest lords of an entire kingdom were decked out in all their finery, and had come here just to see Catalina, and Richard be married. King Richard, Queen Beatrice Richard Ratcliffe, William Catesby, Francis Lovell, John de la Pole, and Thomas Howard served as witnesses for the prince, while the Iberian diplomats and her ladies in waiting served as Catherine’s witnesses. The vows were said, the contract that had been ironed out months ago signed, and they were married. They had exchanged many letters since their betrothal, outlined in the Treaty of Medina del Campo in 1489. In fact, neither of them remembered a time when they had not been betrothed to each other, since they had been toddlers at the time.

As the sun slowly rose higher in the sky, promising to be a long and warm day, the wedding party left the chapel and proceeded outdoors to the tournament grounds. The workers had just put the finishing touches on this enormous, quarter mile to a side, combination fairgrounds and tournament field. Already the market gardeners, food vendors, sellers of ornaments and decoration and frippery of all kinds, bankers, wool and cloth and velvet and silk merchants had set up their stalls in the fairgrounds, ready for the hungry nobility and people of quality. The king had made the tournament open to the public, but of course his men guarded the perimeter and the entrance, only letting the more affluent of London’s commoners inside. Otherwise, the entire city would have come to join the fun.

There were typical carnival games, strongmen who would arm wrestle or body wrestle on a bet, games of skill and chance, riddle asking, kissing booths (the actual prostitutes had to roam outside the fairgrounds), and more. Tubs of cool water were stationed here and there for hot, sweaty heads to be dunked in, for it was already quite warm outside. The paths of the fair led by design to the tournament grounds, which spectators standing in the fairgrounds could watch from one side. After quick refreshments and declarations of intentions and bets, the men who would compete in the tournament entered the huge tournament house, where their arms and armour were kept and on top of which the stands had been built. They took a while to get ready, bantering with each other and their squires and attendants, visited by family and admirers, checking and rechecking that everything was right.

First came team combats, with various numbers of teams and team sizes for each combat. There were enough combatants, noblemen and their sons and knights and squires and even some very wealthy burghers, that not all needed to be on the field at once to make a good show. Some of the combats were on horse, others on foot, and a few were not combats at all, but archery contests. Each round of competition had its own prize, for the fights on horseback it was a finely made hand-sized golden horse, for the foot melee it was a sum of gold and fine silk robes, tailored to the winner, and for the victor in archery it was a golden arrow, three feet long and decorated with tiny stags and hogs and hares.

The men fought with light, blunt wooden maces and swords that were well made and did not break. The affair was fully honourable, if any man’s helmet came unlaced then all fighting nearby had to stop until he had indicated that it was on correctly again. Judges who darted here and there on horseback or on foot, with full white sashes or surcoats, ensured proper enforcement of the rules (eliminating seven violators throughout the day) and tallying of points or wins.

Victories against opponents in the horseback melee awarded two points each, a point was awarded to every member of the victorious team, and three points each to the best combatant on each team, chosen by the judges. In the foot melee individual victories were worth only one point, and two points went to the best combatant on each team. The archery contest had no points for anything but first place, but the first-place man got a hefty, welcome bonus of seven points. If he did decently otherwise, he would be guaranteed a spot in the final tournament.

Of the two hundred or so combatants, the thirty-two who netted the most points throughout the day would be paired for one-on-one combats of elimination, guaranteed a prize that rose higher with each tier they achieved. Among the thirty-two were squires and burghers, men who had astounded with their martial talent despite relatively low birth, as well as more accomplished men. Among the more noble, well known to the royal court, were Henry Algernon Percy, the bastards John of Gloucester and Arthur Plantagenet, who wouldn’t have missed a chance to beat each other to bits for the world, three de la Pole brothers (John, Edmund, and Richard) who were successively born nine years apart, three Howards; Thomas, Count of Surrey, heir to the dukedom and his brothers Edward and Edmund. George Talbot, 4th Earl of Shrewsbury, also joined the fighters.

These had all shown extraordinary prowess and bravery, but the smartest had worked only hard enough, conserving their energy, to reach this point. Now the old points were gone, they were all equal for now, guaranteed ten pounds sterling and more as they progressed successfully. The victor would have one thousand pounds and the best made ceremonial arms, to be tailor made. The freshest was John of Gloucester, who had won the archery contest and so had seven points with much less effort than anybody else. But skill and chance played as much of a role as physical freshness.

For thirty-two combatants there would be thirty-two combats, thirty one as the regular course of elimination went on, and one between the losers of the semi-finals to determine third and fourth place. Places were determined by drawing numbers from a box, and a panel of judges watched from up close. The well-made wooden swords and maces were replaced with real ones. In the first combat John of Gloucester faced a squire, and the boy didn’t stand a chance. In other highlights, Henry Percy handily defeated a younger knight, then was himself eliminated by John de la Pole. That’s as far as John got though, as John of Gloucester defeated him in the third tier of fights. Henry Algernon Percy, too, showed great skill in combat and made it to the third tier, when he faced Edward Howard. Though young Edward wasn’t much interested in court life, he had no lack of physical strength or bravery and Henry Algernon, already flagging from trying so hard in the melees earlier in the day, stood no chance. In the next round, the semi-finals, Edmund Howard lost to Arthur Plantagenet, but was in fact the first to be able to even hit him that day.

The other semi-final pitted tireless John of Gloucester against Richard Sharpe; a seventeen-year-old squire who had in an upset defeated a knight. The young man met his match in John of Gloucester, and in the combat between himself and Surrey (the losers in the semi-finals, to determine the third-place winner) he lost once again...but what an honour it was for a squire, more boy than man! to lose so late, after defeating so many august names! The king took note of the young man at once.

And so, as they had hoped, archenemies John of Gloucester and Arthur Plantagenet faced off in the finals. This had not even been planned, but bookies and refreshment vendors alike rejoiced as people rushed into the stands and pushed against the fences built around the tournament ground, eager to see these two violent men in their prime face off. Many bets were taken, and a few fights broke out between less than noble supporters of the two.

John wore no less than seven scarves on his arm including one from his wife Eleanor Percy who was expecting their third child and one from his sister Katherine, Countess of Pembroke. He was thirty-three years old by now and father to a son and daughter.

Arthur wore scarfs from several admiring ladies of the court. Tall, blond, and handsome, Arthur cut a fine figure opposite short, dark-haired John. King Richard, watching, imagined that this was how his brother Edward IV and he had once looked, long ago, when juxtaposed.

At a signal from the judges the two men strapped their helmets on, and the combat began. They both circled slowly, warily, knowing that the other would not hesitate to do as much damage as possible. It was also a great opportunity to rest a bit more, and for a bit of showmanship. Each turned a few times toward the crowd, pretending to be bored drunk, amusing the crowd. After a few minutes they had prepared themselves mentally, and the combat began.

Slowly, testing each other--for the two had never fought with swords before, to have done so would have been to try to kill each other--the fight between these skilled swordsmen turned into a kind of dance. They wore good enough armour, but a blow from a mace, which both had chosen, could easily beat the breath out of a man and leave him helpless in the dirt. Best to dance around and avoid blows, while trying to score one of your own.

Still, it was not unexciting in the least. Many glancing blows were hit, one or the other of them would stagger or trip, to groans and cheers and gasps from the crowd. The royal court was at the edge of its seats. John hit Arthur’s knee from the side, and Arthur increasingly began to favour that leg, hissing in obvious pain. Arthur hit John a glancing blow to the crest of his helmet that made his ears ring, and he reeled dizzily for a minute, barely avoiding Arthur’s eager blows, now that he had the advantage.

At one point John stepped toward Arthur, whose hurt knee slowed him down to a crawling pace and struck. With a titanic effort Arthur sidestepped the blow by putting all his weight on the bad knee, and dove toward John, tackling him to the ground. Arthur sat up and began to pummel him with the handle of his mace, denting the helmet and breastplate while leaving his own body unexposed.

John, struggling and feeling Arthur’s strong but thankfully weakening blows, tried to do something. His face was turned sideways, he breathed the trampled dust of the field and he couldn’t see anything for the sweat in his eyes. He couldn’t muster the breath to shout that he yielded. But he knew that he could really be hurt if this went on, perhaps even killed! Despite their enmity they wouldn’t stoop to murder, but anything could happen in a tournament. But John still had hold of his mace. With all the strength he could muster he swung it upward blindly and was rewarded with contact that sent Arthur sliding sideways, more unbalanced than anything.

John lay there, face turned up and gasping for breath, wanting more than anything in the world to sleep after this long day, but knew that he couldn’t. He leaned up onto his left elbow, holding his mace like a talisman, and blinked sweat from his eyes. Finally, he could see, blurrily, Arthur on the ground in front of him trying to get up, looking for all the world like a turtle on its back. The crowd was mad with shouts and cheers, but John’s ears still rang from the blows he’d taken.

After a minute of gathering his breath, John sat up with a groan, then stood shakily. His legs were sore from exertion. Now that he stood, he saw that Arthur’s helmet had been knocked off, and his blond hair was streaked with red.

Oh God no, was he dead? But no, he moved, he had just cut his head on a rock. The judges moved closer, to determine if Arthur was well enough to continue. Would he die? John shouted for the judges to come closer and treat Arthur. But no, Arthur stretched his arm out suddenly and grabbed his helmet, sitting up. Staring hatefully at John for apparently stealing victory, Arthur strapped his helmet on himself, hands slippery with sweat. Finally done he went to his knees. But then, instead of standing, he dove forward and swept with his mace, using his long reach, and hitting John in the ankle.

There was a flare in his ankle that didn’t abate as John fell again, and when he’d recovered enough to look around, he saw that Arthur was going to be upon him again. Damn cheating bastard! But Arthur faltered for a second as he realized that he’d broken John’s ankle, a terrible injury. With this brief chance John took careful aim and threw his mace like a spear, in one final effort. It struck true, hitting Arthur’s helmet high and sending it flying, and sending Arthur himself sprawling.

John didn’t even wait to see if Arthur wanted to continue the fight. He lay onto his back gratefully and gasped the fresh air.

The Londoner’s would immortalise the joust as The Battle of the Bastards.

After the evening’s celebrations had been over, the bedding ceremony took place. Prince Richard was in a pensive mood, Catalina feeling unsure, the other people high and boisterous. Both had been dressed in nightshirts, the bed made of layers from straw, canvas, a beaten feather mattress and stretched sheets, with a canopy above and curtains around it. The bishops were reciting Latin prayers and after the young couple had been left alone in their chamber.

Despite the exhaustion from the long day and elaborate ceremonies before that it appeared that a consummation took place that night. Catalina and Richard remained together in Sheen Palace for another week, until the Prince were sent back to Ludlow in the Welsh marshes. The choice to send him away seemed to be the King’s as well as Queen Beatrice His duties could not wait forever, but he was to go alone. To send the princess with him to Ludlow, a strange palace so soon seemed unwise, when Catalina could learn much more of her duties and future skills at court. Beatrice also seemed to be concerned of her son indulging to much in romantic affection with his new bride.

The prince and princess of Wales took a tender farewell on the 25th of May and Catalina watched as her husband disappeared from her eyes until autumn. During the summer, the princess rarely strayed far from the Queen and princess Beatrice. Indeed, both accompanied her on court functions, almsgiving and sat with her and the king in the Court of Appeals to listen and grant petitions from seekers coming far and wide.

Beatrice had at that point assessed her daughter in-law’s strength and weaknesses. Most notable, Catalina had no sense of money. Having been brought up understanding that generosity were the virtues of a royal lady, she was inclined to spend freely towards her friends and poor. The ever-economical queen who had since childhood kept her eyes on the accounts sought to enlighten the girl on housekeeping, making her take lessons with her and the duchess of Norfolk, Elizabeth Tilney.

Elizabeth Tilney, Duchess of Norfolk

The summer was a good one, with celebrations and hunts was a grand affair and the Infanta would enjoy herself. Frequent letters arrived from Ludlow much to her delight. With the Queen’s steely hand to guide her, Catalina had managed to control her household and even added to several ladies in waiting, Elizabeth Howard and Margaret Scrope. The Spanish infanta had been gently transitioned into the Princess of Wales, now called Catherine to herself and the english court.

Author’s Note: So a lot of butterflies in this chapter; most importantly Beatrice of Portugal is a much better mother in law than Elizabeth of York and better be able to take care and charge of Catharine than otl. Elvira Manuel and her husband, who were pieces of work otl are not in this story, and Richard III is not Henry VII, so everyone is a lot happier. Much better start and Catherine is not yet in Ludlow, even if the castle is very nice after the fire thanks to Beatrice who refused to send her young son there until it had been repaired, refurbished and much healthier and nicer that otl. Catherine did not have a good sense of money otl, so I fixed that. Elizabeth Tilney will live a lot longer because I said so. And yes, I know Katherine Plantagenet and the Earl of Pembroke was dead long before 1501, but I’m almighty on this TL, so they live.

Chapter 22 – England in 1501

The voyage from the port of Ferrol in Galicia to Southampton in Hampshire was uneven for the seven ships departing after Easter in 1502. Atlantic winds did not bother the ships much, as they strived to avoid the temperamental Bay of Biscay. The English channel on the other hand, seemed to be in a bad mood when they rounded the duchy of Brittany as a storm seemed hellbent on making the last days sour for everyone onboard. The ships docked at Southampton in late evening, a little worse for wear. Days of rains had soured the mood of the crew, but in the hours before the afternoon the sun had broken through the cloudy sky, framing the small fleet seen across the horizon. Infanta Catalina of Castile and Aragon was able to get up on the damp deck and enjoy the warmth of spring as her new homeland was sighted in the distance. In her hands she clutched the saint medallions from Santiago de Compostela cathedral. Both had been purchased before the journey. Saint Brendan for a safe seafaring journey and Saint George for her new kingdom. The city of Ferrol where her ships left was also the starting point for the Camino Inglés or The English Way for those on the path of pilgrimage. Catalina would have seen plenty of english men and women at the time when she left from the cathedral to the port. Rumours had spread that the Princess of Wales to be would leave for her marriage and the pilgrims in the areas would be the first Englishmen to greet their future queen to be.

The journey of Infanta Catalina to England

The mayor of Hampshire would receive the Infanta and her retinue and their first night was spent in the castle of Southampton, where warm food and roaring fires awaited them. The old fortress had been renovated by King Richard several times and the Spaniards could relax for a few days in comfort while they got their land legs back. Messengers were already racing towards the King and Queen, and Prince Richard. The royal family were at the time close to Winchester Castle where the bride and groom would meet at last. Queen Beatrice knew that the Spanish rigid court etiquette prohibited an infanta from entertaining her future husband or father-in-law before marriage had been completed. And even more importantly, Beatrice knew that for her new daughter in law, coming to England from the Iberian kingdoms could be disorienting. Fortunately, it said nothing of mothers in law, so Beatrice took a splendid entourage with her as well as her eldest daughter, Bea to greet Catalina. The king and prince arrived in Winchester, where it was abuzz with preparations for several days.

The meeting between Queen and Princess was a very positive one. At the age of sixteen Catalina was a fair skinned girl with lustrous auburn hair, a round face and blue eyes. She was of average height but seemed taller with her posture. Prince Richard was not overly tall either, but would hit another growth spurt after the wedding. While he would never be as tall as his uncle Edward IV, he grew to be taller than his father.

Winchester had prepared a royal welcome for the new princess and when the royal entourage crossed the Westgate the city erupted in joy. Merchants had dressed in fine clothing, ladies their most colourful gowns, and hangings from the buildings showed both silks, tapestries, and cloth of gold and silver. The white rose of York decorated every corner and children threw flowers and herbs along the main road in front of the horses and carriages. The city aldermen meet the Queen and princesses on the steps of Winchester cathedral along with the bishop and churchmen. The splendour of the cathedral impressed the Spaniards along with the celebrations. For a daughter of Isabel the Catholic, the religious building must have been a great comfort and an opportunity to reflect on the past weeks.

It was here Catalina finally met the young man she had left Spain for, the purpose of her life since she was a toddler. Since the pair had already been married by proxy, the meeting was accepted by all partners. The Prince of Wales proved a sight for her seeking eyes. Richard was a young man of fifteen, with thick dark hair and grey eyes marked by heavy eyebrows. Still somewhat lanky, the english royal clothing padded him out somewhat, making him an impressive figure. The prince had dressed up for meeting his bride; cloth of gold and silk doublet, with a velvet overrobe trimmed with fur.

The royal party left Southampton to travel towards London after a few days, moving at a leisurely pace. Commoners gathered at the roads to catch a glimpse of the foreign princess, marvelling of her rich dresses in Spanish style and her entourage. The entry into London had been carefully planned. Catalina wore a splendid gown in cloth of gold and embroidered silk with an overrobe of crimson velvet lined with fur and her rich auburn hair hung down in glossy waves with a carnation-coloured cap on top. Her ladies had dressed in black to avoid outshining their princess and covered their hair with mantillas. Every Spaniard had been partnered with an english of the same status. Catalina rode a richly harnessed mule and was accompanied by Princess Beatrice, who wore cloth of silver and dark blue velvets. The papal legate rode next to her while the king’s heralds lead the way. Commoners perched themselves somewhat recklessly in windows, roofs, and other high places to observe the progression. The display of Castilian pride was high and while London was no stranger to Spaniards in the city, this went above and beyond. The reactions were somewhat mixed. The women in the entourage were seen as strange due to their black clothes and the future Lord Chancellor Thomas More, remarked in one of his few crueller moments, that some of her ladies seemed like “hunchbacked, undersized, barefoot pygmies from Ethiopia.” Later in life, More would become a loyal servant to the so-called pygmies’ princess and her York king.

Several pageants had been constructed around the city for the entry. They were colourful and filled by symbolism. Actors performed on the stages, dressed as saints. Lions, dragons, white roses and horses adorned them while the company wound their way towards Lambeth Palace, the residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury. The mayor of London, dressed in crimson satin, guided them from the various pageants. Two dozen sheriffs and aldermen accompanied them in black and scarlet. The city itself showed its best face for the day. The buildings had been hung with tapestries and silks in bright colours. Musicians played various instruments and Catalina and Beatrice could enjoy the ballads performed for them. While Thomas More had dismissed the princess’s ladies, he had nothing but praise for the infanta herself. “Ah, but the lady! Take my word for it. She thrilled the hearts of everyone: she possesses all the qualities that make for beauty in a very charming young woman. Everywhere she receives the highest of praises; but even that is most inadequate. I do hope this highly published union will prove a happy omen for England.”

Richard, Prince of Wales and Infanta Catalina on their wedding day

The wedding took place in St Paul’s Cathedral. Edmund, Duke of York fourteen years old at the time, escorted her from Lambert Castle to the cathedral doors. The ceremony was simple and quick, but no less magnificent for it. The greatest lords of an entire kingdom were decked out in all their finery, and had come here just to see Catalina, and Richard be married. King Richard, Queen Beatrice Richard Ratcliffe, William Catesby, Francis Lovell, John de la Pole, and Thomas Howard served as witnesses for the prince, while the Iberian diplomats and her ladies in waiting served as Catherine’s witnesses. The vows were said, the contract that had been ironed out months ago signed, and they were married. They had exchanged many letters since their betrothal, outlined in the Treaty of Medina del Campo in 1489. In fact, neither of them remembered a time when they had not been betrothed to each other, since they had been toddlers at the time.

As the sun slowly rose higher in the sky, promising to be a long and warm day, the wedding party left the chapel and proceeded outdoors to the tournament grounds. The workers had just put the finishing touches on this enormous, quarter mile to a side, combination fairgrounds and tournament field. Already the market gardeners, food vendors, sellers of ornaments and decoration and frippery of all kinds, bankers, wool and cloth and velvet and silk merchants had set up their stalls in the fairgrounds, ready for the hungry nobility and people of quality. The king had made the tournament open to the public, but of course his men guarded the perimeter and the entrance, only letting the more affluent of London’s commoners inside. Otherwise, the entire city would have come to join the fun.

There were typical carnival games, strongmen who would arm wrestle or body wrestle on a bet, games of skill and chance, riddle asking, kissing booths (the actual prostitutes had to roam outside the fairgrounds), and more. Tubs of cool water were stationed here and there for hot, sweaty heads to be dunked in, for it was already quite warm outside. The paths of the fair led by design to the tournament grounds, which spectators standing in the fairgrounds could watch from one side. After quick refreshments and declarations of intentions and bets, the men who would compete in the tournament entered the huge tournament house, where their arms and armour were kept and on top of which the stands had been built. They took a while to get ready, bantering with each other and their squires and attendants, visited by family and admirers, checking and rechecking that everything was right.

First came team combats, with various numbers of teams and team sizes for each combat. There were enough combatants, noblemen and their sons and knights and squires and even some very wealthy burghers, that not all needed to be on the field at once to make a good show. Some of the combats were on horse, others on foot, and a few were not combats at all, but archery contests. Each round of competition had its own prize, for the fights on horseback it was a finely made hand-sized golden horse, for the foot melee it was a sum of gold and fine silk robes, tailored to the winner, and for the victor in archery it was a golden arrow, three feet long and decorated with tiny stags and hogs and hares.

The men fought with light, blunt wooden maces and swords that were well made and did not break. The affair was fully honourable, if any man’s helmet came unlaced then all fighting nearby had to stop until he had indicated that it was on correctly again. Judges who darted here and there on horseback or on foot, with full white sashes or surcoats, ensured proper enforcement of the rules (eliminating seven violators throughout the day) and tallying of points or wins.

Victories against opponents in the horseback melee awarded two points each, a point was awarded to every member of the victorious team, and three points each to the best combatant on each team, chosen by the judges. In the foot melee individual victories were worth only one point, and two points went to the best combatant on each team. The archery contest had no points for anything but first place, but the first-place man got a hefty, welcome bonus of seven points. If he did decently otherwise, he would be guaranteed a spot in the final tournament.

Of the two hundred or so combatants, the thirty-two who netted the most points throughout the day would be paired for one-on-one combats of elimination, guaranteed a prize that rose higher with each tier they achieved. Among the thirty-two were squires and burghers, men who had astounded with their martial talent despite relatively low birth, as well as more accomplished men. Among the more noble, well known to the royal court, were Henry Algernon Percy, the bastards John of Gloucester and Arthur Plantagenet, who wouldn’t have missed a chance to beat each other to bits for the world, three de la Pole brothers (John, Edmund, and Richard) who were successively born nine years apart, three Howards; Thomas, Count of Surrey, heir to the dukedom and his brothers Edward and Edmund. George Talbot, 4th Earl of Shrewsbury, also joined the fighters.

These had all shown extraordinary prowess and bravery, but the smartest had worked only hard enough, conserving their energy, to reach this point. Now the old points were gone, they were all equal for now, guaranteed ten pounds sterling and more as they progressed successfully. The victor would have one thousand pounds and the best made ceremonial arms, to be tailor made. The freshest was John of Gloucester, who had won the archery contest and so had seven points with much less effort than anybody else. But skill and chance played as much of a role as physical freshness.

For thirty-two combatants there would be thirty-two combats, thirty one as the regular course of elimination went on, and one between the losers of the semi-finals to determine third and fourth place. Places were determined by drawing numbers from a box, and a panel of judges watched from up close. The well-made wooden swords and maces were replaced with real ones. In the first combat John of Gloucester faced a squire, and the boy didn’t stand a chance. In other highlights, Henry Percy handily defeated a younger knight, then was himself eliminated by John de la Pole. That’s as far as John got though, as John of Gloucester defeated him in the third tier of fights. Henry Algernon Percy, too, showed great skill in combat and made it to the third tier, when he faced Edward Howard. Though young Edward wasn’t much interested in court life, he had no lack of physical strength or bravery and Henry Algernon, already flagging from trying so hard in the melees earlier in the day, stood no chance. In the next round, the semi-finals, Edmund Howard lost to Arthur Plantagenet, but was in fact the first to be able to even hit him that day.

The other semi-final pitted tireless John of Gloucester against Richard Sharpe; a seventeen-year-old squire who had in an upset defeated a knight. The young man met his match in John of Gloucester, and in the combat between himself and Surrey (the losers in the semi-finals, to determine the third-place winner) he lost once again...but what an honour it was for a squire, more boy than man! to lose so late, after defeating so many august names! The king took note of the young man at once.

And so, as they had hoped, archenemies John of Gloucester and Arthur Plantagenet faced off in the finals. This had not even been planned, but bookies and refreshment vendors alike rejoiced as people rushed into the stands and pushed against the fences built around the tournament ground, eager to see these two violent men in their prime face off. Many bets were taken, and a few fights broke out between less than noble supporters of the two.

John wore no less than seven scarves on his arm including one from his wife Eleanor Percy who was expecting their third child and one from his sister Katherine, Countess of Pembroke. He was thirty-three years old by now and father to a son and daughter.

Arthur wore scarfs from several admiring ladies of the court. Tall, blond, and handsome, Arthur cut a fine figure opposite short, dark-haired John. King Richard, watching, imagined that this was how his brother Edward IV and he had once looked, long ago, when juxtaposed.

At a signal from the judges the two men strapped their helmets on, and the combat began. They both circled slowly, warily, knowing that the other would not hesitate to do as much damage as possible. It was also a great opportunity to rest a bit more, and for a bit of showmanship. Each turned a few times toward the crowd, pretending to be bored drunk, amusing the crowd. After a few minutes they had prepared themselves mentally, and the combat began.

Slowly, testing each other--for the two had never fought with swords before, to have done so would have been to try to kill each other--the fight between these skilled swordsmen turned into a kind of dance. They wore good enough armour, but a blow from a mace, which both had chosen, could easily beat the breath out of a man and leave him helpless in the dirt. Best to dance around and avoid blows, while trying to score one of your own.

Still, it was not unexciting in the least. Many glancing blows were hit, one or the other of them would stagger or trip, to groans and cheers and gasps from the crowd. The royal court was at the edge of its seats. John hit Arthur’s knee from the side, and Arthur increasingly began to favour that leg, hissing in obvious pain. Arthur hit John a glancing blow to the crest of his helmet that made his ears ring, and he reeled dizzily for a minute, barely avoiding Arthur’s eager blows, now that he had the advantage.

At one point John stepped toward Arthur, whose hurt knee slowed him down to a crawling pace and struck. With a titanic effort Arthur sidestepped the blow by putting all his weight on the bad knee, and dove toward John, tackling him to the ground. Arthur sat up and began to pummel him with the handle of his mace, denting the helmet and breastplate while leaving his own body unexposed.

John, struggling and feeling Arthur’s strong but thankfully weakening blows, tried to do something. His face was turned sideways, he breathed the trampled dust of the field and he couldn’t see anything for the sweat in his eyes. He couldn’t muster the breath to shout that he yielded. But he knew that he could really be hurt if this went on, perhaps even killed! Despite their enmity they wouldn’t stoop to murder, but anything could happen in a tournament. But John still had hold of his mace. With all the strength he could muster he swung it upward blindly and was rewarded with contact that sent Arthur sliding sideways, more unbalanced than anything.

John lay there, face turned up and gasping for breath, wanting more than anything in the world to sleep after this long day, but knew that he couldn’t. He leaned up onto his left elbow, holding his mace like a talisman, and blinked sweat from his eyes. Finally, he could see, blurrily, Arthur on the ground in front of him trying to get up, looking for all the world like a turtle on its back. The crowd was mad with shouts and cheers, but John’s ears still rang from the blows he’d taken.

After a minute of gathering his breath, John sat up with a groan, then stood shakily. His legs were sore from exertion. Now that he stood, he saw that Arthur’s helmet had been knocked off, and his blond hair was streaked with red.

Oh God no, was he dead? But no, he moved, he had just cut his head on a rock. The judges moved closer, to determine if Arthur was well enough to continue. Would he die? John shouted for the judges to come closer and treat Arthur. But no, Arthur stretched his arm out suddenly and grabbed his helmet, sitting up. Staring hatefully at John for apparently stealing victory, Arthur strapped his helmet on himself, hands slippery with sweat. Finally done he went to his knees. But then, instead of standing, he dove forward and swept with his mace, using his long reach, and hitting John in the ankle.

There was a flare in his ankle that didn’t abate as John fell again, and when he’d recovered enough to look around, he saw that Arthur was going to be upon him again. Damn cheating bastard! But Arthur faltered for a second as he realized that he’d broken John’s ankle, a terrible injury. With this brief chance John took careful aim and threw his mace like a spear, in one final effort. It struck true, hitting Arthur’s helmet high and sending it flying, and sending Arthur himself sprawling.

John didn’t even wait to see if Arthur wanted to continue the fight. He lay onto his back gratefully and gasped the fresh air.

The Londoner’s would immortalise the joust as The Battle of the Bastards.

After the evening’s celebrations had been over, the bedding ceremony took place. Prince Richard was in a pensive mood, Catalina feeling unsure, the other people high and boisterous. Both had been dressed in nightshirts, the bed made of layers from straw, canvas, a beaten feather mattress and stretched sheets, with a canopy above and curtains around it. The bishops were reciting Latin prayers and after the young couple had been left alone in their chamber.

Despite the exhaustion from the long day and elaborate ceremonies before that it appeared that a consummation took place that night. Catalina and Richard remained together in Sheen Palace for another week, until the Prince were sent back to Ludlow in the Welsh marshes. The choice to send him away seemed to be the King’s as well as Queen Beatrice His duties could not wait forever, but he was to go alone. To send the princess with him to Ludlow, a strange palace so soon seemed unwise, when Catalina could learn much more of her duties and future skills at court. Beatrice also seemed to be concerned of her son indulging to much in romantic affection with his new bride.

The prince and princess of Wales took a tender farewell on the 25th of May and Catalina watched as her husband disappeared from her eyes until autumn. During the summer, the princess rarely strayed far from the Queen and princess Beatrice. Indeed, both accompanied her on court functions, almsgiving and sat with her and the king in the Court of Appeals to listen and grant petitions from seekers coming far and wide.

Beatrice had at that point assessed her daughter in-law’s strength and weaknesses. Most notable, Catalina had no sense of money. Having been brought up understanding that generosity were the virtues of a royal lady, she was inclined to spend freely towards her friends and poor. The ever-economical queen who had since childhood kept her eyes on the accounts sought to enlighten the girl on housekeeping, making her take lessons with her and the duchess of Norfolk, Elizabeth Tilney.

Elizabeth Tilney, Duchess of Norfolk

The summer was a good one, with celebrations and hunts was a grand affair and the Infanta would enjoy herself. Frequent letters arrived from Ludlow much to her delight. With the Queen’s steely hand to guide her, Catalina had managed to control her household and even added to several ladies in waiting, Elizabeth Howard and Margaret Scrope. The Spanish infanta had been gently transitioned into the Princess of Wales, now called Catherine to herself and the english court.

Author’s Note: So a lot of butterflies in this chapter; most importantly Beatrice of Portugal is a much better mother in law than Elizabeth of York and better be able to take care and charge of Catharine than otl. Elvira Manuel and her husband, who were pieces of work otl are not in this story, and Richard III is not Henry VII, so everyone is a lot happier. Much better start and Catherine is not yet in Ludlow, even if the castle is very nice after the fire thanks to Beatrice who refused to send her young son there until it had been repaired, refurbished and much healthier and nicer that otl. Catherine did not have a good sense of money otl, so I fixed that. Elizabeth Tilney will live a lot longer because I said so. And yes, I know Katherine Plantagenet and the Earl of Pembroke was dead long before 1501, but I’m almighty on this TL, so they live.

I thought so indeed!Great timing girl! A perfect day for an english chapter!

And loved the bastards reference!

And the battle of the bastards were a part of the writing in a chapter me and my former partner philippe le bel write in our Richard III TL that I'm recycling.

Cool!I thought so indeed!

And the battle of the bastards were a part of the writing in a chapter me and my former partner philippe le bel write in our Richard III TL that I'm recycling.

Threadmarks

View all 58 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 47 - England from 1523 to 1526 Chapter 48 - Brabant, France and England from 1525 to 1527 Chapter 49 - Spain and the Holy Roman Empire 1523 to 1525 Chapter 50 - Spain and the Holy Roman Empire from 1525 to 1526 Chapter 51 - Brabant, France and the Holy Roman Empire in 1527 Chapter 52 - Spain from 1527 to 1528 Chapter 53 – England in September of 1528 Chapter 54 - Brabant and France in 1528

Share: