38. Jack Gilligan (D-OH)

38. Jack Gilligan (Democratic-OH)

January 20, 1977 - May 29th, 1981

“Any real accomplishment in the world reflects the efforts of a lot of people… for an individual to claim personal responsibility is the height of arrogance.”

January 20, 1977 - May 29th, 1981

“Any real accomplishment in the world reflects the efforts of a lot of people… for an individual to claim personal responsibility is the height of arrogance.”

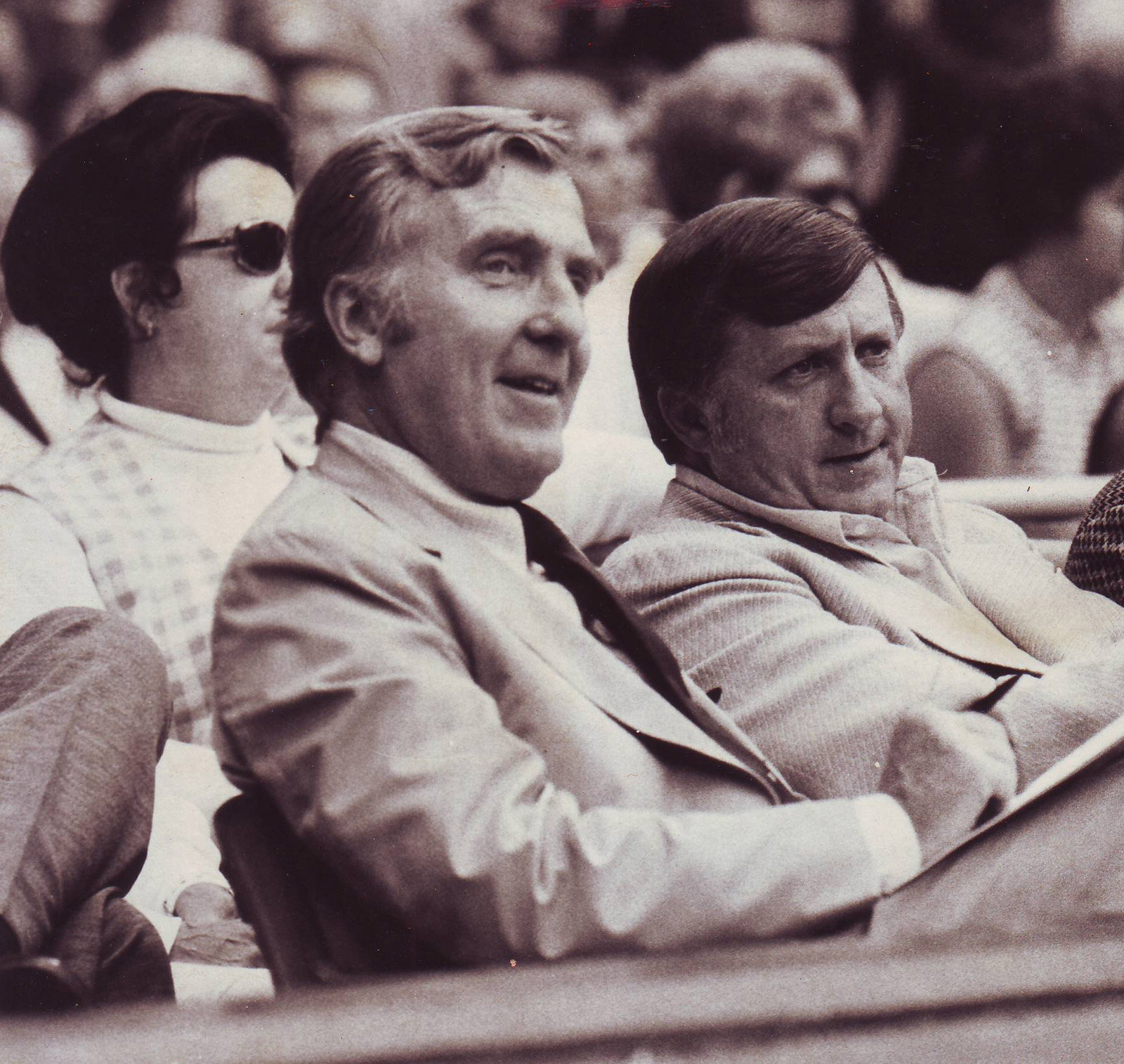

Virtually every American of a certain age can see it. A neatly-kept wave of graying red hair. A lean, craggy grin and sharp eyes capable of disarming virtually any opponent. A florid face that seemed to redden several shades at the drop of a hat. A demeanor equal parts charming and irascible, witty and acerbic, passionate and aloof. A feverish tone that made every speech sound a bit like a sermon. The image of President Gilligan - of Jack - remains burned into a generation’s collective consciousness.

John Joyce Gilligan never wanted to be a politician. His ultimate goal in life was, devout Catholic he was, the seminary. But after Pearl Harbor, the would-be Jesuit followed the calling of Uncle Sam like so many others and enlisted in the Navy as a gunnery officer. Upon returning from the Pacific, Silver Star in hand, the Gilligans - Jack had married his childhood love Katie while on leave from the war - settled down in their native Cincinnati, where Jack taught literature at his alma mater, Xavier University. So it seemed that the Gilligans would enter into the quiet homecoming of many GIs to their families.

What drew him into politics was Adlai Stevenson's 1952 presidential campaign. Though the eventual president’s first campaign faced long odds and a general public fatigued with twenty years of Democratic rule, like countless other liberals of the era it ignited within Gilligan a firm belief in politics as public service. Soon after, he elected to run for a city council seat in Cincinnati, which he won despite the city’s Republican leanings. After Adlai Stevenson’s victory, Gilligan decided then and there that he would follow his idol to Washington. 1962 was no year for Democrats, though, especially not in a typically Republican environment like the Taft family’s hometown, and Gilligan’s first congressional bid fell short as voters seemingly rejected New America. Dejected but defiant, Jack Gilligan immediately turned his focus to a campaign for 1964, a race he privately labeled as do or die for his burgeoning ambitions for high office. Despite a slate of Republican victories statewide, a bare margin of just a thousand votes sent Jack Gilligan to Washington.

There, Representative Gilligan quickly made a name for himself within the Ohio delegation. This was not due to his effectiveness - the Democrats were only in the barest of majorities during his first term, and this was often overshadowed by Bill Fulbright’s seeming disinterest in the affairs of Capitol Hill beyond his pet education reforms. Instead, it was due to his work at home. Apart from being an effective representative for people who had sparsely been represented by a Democrat, he was unique within the Ohio Democratic Party. Dominated by Frank Lausche’s conservative multi-ethnic machinery, the Ohio Democrats were often beholden to his independent style and “small-d democrat” approach. Jack Gilligan was having none of this, a liberal Stevensonian through and through. He privately offered many, many tempestuous rants against “Frank the Fence,” and often ignored calls from his representatives among the Ohio Democrats. Instead, Gilligan spent his time wooing three key lobbies that would guide his career - the activists, the unions, and the racial minorities. At first, this seemed suicidal, but amidst a Democratic Party torn asunder by issues of import to these exact groups, Gilligan displayed a crossover strength that continued his career in a nominally Republican district. Even so, he was decidedly in the minority in Ohio, and Lausche and his minions consistently reminded him of it.

Then, on November 5th, 1968, Frank Lausche lost. His fence-sitting had cost him vital labor support, and his focus on white ethnic groups may have worked well in the past, but it made him seem an out of touch machine boss when Republicans promised real action on civil rights and the disorder caused by it. Not only had Lausche lost, he had lost because the exact voter blocs in Ohio that loved Jack Gilligan had sat on their hands. The results were clear to every single Ohio Democrat: Gilligan the iconoclastic liberal was right, and Lausche the small-d democrat wrong.

Once scorned for his oddities, now Gilligan was the savior of the party. He acted as if the party courted him to run, but the truth is he knew he wanted to chase freshman Senator Robert Taft Jr. seat in 1970 ever since he realized Lausche’s grip had slipped. When he did run, he was virtually unopposed in the primary, even despite a relatively light legislative record in the minority. Taft tried to hit him on this, treating him as a do-nothing liberal lightweight, but Gilligan debuted a prototype of the campaign strategy that would become so familiar in the future. An army of student volunteers canvassed the state, getting voters registered and engaged with the Gilligan campaign - and where the campaign didn’t have resources, Gilligan’s labor point man Bill Kircher wrung cash, manpower, and materials out of the AFL-CIO to compensate. The first of his memorably quirky ads, “Inferno,” saw Gilligan standing on a bridge, behind him a backdrop of the Cuyahoga River on fire (as it often did in those days due to oil slicks), pointing out that Senator Taft had voted against multiple bills aimed at cleaning up the blaze he gestured at behind him due to lobbying by the owners of the manufacturing plants behind the flaming river. Evidently, Ohioans agreed with his closing question “Isn’t it time we elected someone who puts out fires?” as Gilligan beat Taft fairly decisively.

Now a rising star in the Democratic caucus, Jack Gilligan focused on keeping his name out there. He ensured his most notable campaign promise was paid off when sponsoring the bill authorizing the Department of Environmental Protection, discussing with President Kuchel its use to break down pollution in the Cuyahoga and even giving a televised press conference from the very same bridge the ad was shot on when cleaning began. He helped to maneuver some of the glut of new NASA spending to a new research & development facility outside Cleveland, authored a bipartisan bill dealing with the transition from mental institutions to more humane treatment plans, and aided in the drafting of regulations on strip-mining. None of this, except maybe the DEP, was the type of action that made a contender for the presidency. But Gilligan had risen through the ranks because he knew how to cultivate relationships with the liberal grassroots, and cultivate he did. He was, after Wayne Morse’s passing, the only incumbent Democratic legislator to routinely address the SDS’ annual convention. A highly publicized meeting with Cesar Chavez after President Kuchel revived the Braceros raised eyebrows, and the UFW’s negotiated entry into the AFL-CIO later that year had Senator Gilligan’s fingerprints all over it to anyone in the know. ADA lawyers and policy wonks practically lived out of his office, helping him draft expansive legislation on everything from tuition fees to healthcare reform to labor law. Though he was not necessarily the most prominent member of the body, often outshined by veterans like Hubert Humphrey and Richard Nixon, in the young countercultural bastions of activist left-liberalism Jack Gilligan got approving mentions.

This was exactly what Gilligan wanted. By the time he had entered the Senate he knew his goal was the White House. The 1972 race had confirmed his greatest suspicions - the Democratic Party was rudderless, on one hand lacking leadership due to Tommy Kuchel’s apathetic popularity but on the other lacking much of the machinery that propelled it through the 1960s. Come 1974, as the race geared up in earnest, the party had few candidates actively seeking the office, especially once Leader Humphrey and his protege Governor Mondale both ruled out a bid. Richard Daley was seemingly the only one of the old bosses left, with Jesse Unruh’s scandals locking California in for the right for another generation and men like John Moran Bailey succumbing to their advanced age. As such, the only candidate fielded by the smoke-filled rooms was one from the dying Daley, a repeat of his last intervention: the Governor of Illinois, Adlai Stevenson. Adlai the Third was young, he was a liberal-minded reformer, and he looked enough like the old egghead that he was sure to excite the very people who voted him in sixteen years prior.

The name Adlai Stevenson was a double-edged sword, though. While it was true that many of the old-timers adored the old man - he was practically Saint Adlai to Jack Gilligan - the younger crowd, those who had been students during the bloody 60s, saw him as the epitome of more of the same. Adlai the Third’s anti-corruption reforms and his high-concept focus on the nuts and bolts of banking and scientific policy sounded nice on a brochure, but it looked an awful lot like tinkering around the edges, the other side of a coin with Tommy Kuchel’s face on the front. The movement didn’t want that, they didn’t want his obvious overtures to the presidency two years out, they wanted something real. As Gilligan noted to his aides at the SDS convention in November 1974, “you’d think [Adlai Stevenson III]’s Jim Gray the way they’re talking about him.”

So it was that, early in 1975, Jack Gilligan went home to Xavier University to announce his bid for the nomination. Throngs of Cincinnatians came to see their favorite son off, supportive but considering him an unlikely candidate, especially in the face of the heft of Adlai Stevenson’s son. What they - and virtually everybody - didn’t know was that Gilligan’s political team had been single-mindedly focused on replicating his Ohio operation. The primaries had long since been considered window dressing as a show of strength before the convention. Few candidates contested all of them seriously, but few candidates were Jack Gilligan. Gilligan’s campaign team, led by longtime in-house operator Mark Shields and his politically minded daughter Kathleen, reasoned that the primaries could be used to throw a relatively obscure candidate into the national spotlight. A candidate with a devoted activist base - like Jack Gilligan, the student movement’s favorite - could theoretically turn a string of primary wins into an aura of inevitable momentum. So the Gilligan campaign focused on getting college students throughout the early states out and canvassing throughout the back half of 1975, having practically every single door in New Hampshire be knocked on by a twenty-year-old hand. Though Adlai the Third put his name into contention for the first in the nation primary, as is tradition, he didn’t think twice of it - after all, too much campaigning early was a sign of desperation in the eyes of the traditionalists.

The Stevenson camp absolutely thought twice of it when Jack Gilligan carried New Hampshire by three points. His people had earnestly engaged with voters, talking about concrete things Jack Gilligan would do while Stevenson barely found the time to even come to Manchester. Realizing that repeating his father’s aloof intellectualism didn’t play the same with television cameras following Jack Gilligan all around sleepy New Hampshire hamlets, Stevenson quickly moved to salvage it by heading north. But Gilligan was prepared for that eventuality too - his victory in Wisconsin, buoyed by the Madison SDS chapter being one of the most active in the nation, was so total that he managed to defeat Stevenson in wards of Milwaukee thought to be in the bag for the party regulars. Though his own home of Illinois provided some respite, the media had picked up on Jack Gilligan’s smashing victories, proclaiming his momentum as the voice of a generation. This new aura of seriousness as a contender, only aided by Hubert Humphrey’s endorsement, threw open the individual donation floodgates. Stevenson would only carry his home state, making a last serious stand in West Virginia on the basis that a practicing Catholic would lose out in the heavily Protestant Appalachian state. The attempts at using Gilligan’s faith failed brutally. When asked point-blank about the rhetoric coming from Stevenson supporters in West Virginia, Gilligan’s complexion went tomato-red as he held up a flier distributed by said surrogates implying that Gilligan’s Catholicism would be a hindrance to his potential victory. “This sort of backwards trickery,” he practically spat to a reporter’s camera, “has no place here. I didn’t fight for this country in the Pacific to be accused of disloyalty. Governor Stevenson should be ashamed of himself.” Ultimately, the voter backlash to the dirty tricks brought Gilligan the win in West Virginia, and the national media felt comfortable coronating him as the frontrunner and declaring the matter of his faith settled.

Jack Gilligan came to Chicago a conquering hero. Thousands of young people gathered in Grant Park to see the candidate, the man who had not only fought the party establishment but won multiple bouts. Even so, the convention would not be easy, as Gilligan’s blunt rhetoric on civil rights ruffled feathers within the southern delegations. The Gilligan campaign sought to pacify the concerns quickly to avoid a long fight. Florida had been won by favorite son Lawton Chiles in the primaries, after all, so their loyalties seemed up for grabs instead of directly tied to Adlai the Third. After a brief address to the crowds outside the convention hall, Gilligan found his way to a private meeting with the highest southern grandees of the moment - the fucking Louisianans, as his younger staff called them. The haggling with Senator Long and Speaker Boggs took nearly five hours and covered virtually the entire Gilligan campaign platform, but by the time voting started he had emerged with a deal (including the vice presidency for a southerner and key platform planks), ensuring the frontrunner’s first-ballot victory. Though the nominee said a great many things to Chicago in his prime-time acceptance, the most memorable phrase came at the end: “I know what I advocate is bold, and some may not agree. There are those who say that the equal rights of all Americans to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness is a noble goal, but one that must simply wait for a better time. To those who insist that we wait for what Martin Luther King called a more convenient season, we’ve come here as one to tell the nation that it’s time!” Soon, posters of Gilligan with the simple words IT’S TIME were plastered across dormitories throughout America, and the campaign plastered one of the most iconic campaign slogans in American history across ads, signs, buttons, and banners.

At the time, though, Gilligan seemed like more of an oddity. Conservative figures like William F. Buckley gleefully proclaimed his inevitable loss, being no fans of the Kuchel administration but despising the uncouth kids seemingly running the show on the other side of the aisle. Despite a quickly-fizzling challenge from former Indiana Governor Earl Butz as an extension of Reagan’s actor-turned-conservative television host longshot bid, Vice President John Lindsay had emerged as the Republican nominee, effectively promising four more years of Tommy Kuchel’s reasonable progressive conservatism. Given the president’s approval rating, why wouldn’t he? By and large, middle opinion seemed to like the nation as it was in the summer of 1976. Lindsay seemed the clear choice, the respectable centrist compared to the agitations of a network of angry kids.

The election was not defined by the feelings of the summer, though. It would be defined an ocean away. The Bretton Woods system had broadly functioned to make a postwar international economy, but the cracks had begun to show. Privately, officials at the Treasury Department raised alarm bells about how the US dollar was overvalued and as such no longer had enough gold reserves to pay up its theoretical obligations. Kuchel, in his establishmentarian sensibilities, sought to maintain the existing system as best as possible, and focused more on fighting the overvaluation pressures to hopefully normalize the situation. In September 1976, a run on the banks began in Paris but rapidly spread through Europe, and the worst-case scenario came to pass.

The ensuing stock market panic was the worst single-day crash since 1929. Investor confidence plummeted in such an unprecedented situation, leading the nation into deep recession. While President Kuchel shakily addressed the nation urging Congress to pass an economic relief package (incidentally allowing for Childcare’s creation), he took an unprecedented step. Instead of going to Brussels to negotiate with the G10 leadership behind Bretton Woods, he announced his intent to send Vice President Lindsay as the administration’s representative. The move, a political ploy designed to prove Lindsay’s mettle as much as it was a symptom of Kuchel’s depressive episodes where he declared himself “the next Hoover” to any staff who’d listen, was one of unmitigated disaster. Lindsay was a good voice for the administration at home during good times, especially on civil rights and urban affairs, but he was no skilled negotiator. Coverage of the Brussels Summit seemingly showed Lindsay out of his depth next to longstanding giants of the western bloc like Reginald Maudling and Francois Mitterrand, leading to much fodder for MADtv skits. When a harried Lindsay emerged with a tentative deal in the wee hours of the Belgian morning, he seemed to not realize just how much Americans viewed him as having one pulled over on him.

Though the excitement of the volunteer base hadn’t led to much movement in the polls before, stubbornly stuck at 48 for Lindsay to 45 for Gilligan with 7 percent undecided for virtually the whole summer, the entire Brussels debacle was perfect for the Gilligan campaign. First, Lindsay had skipped out on their agreed-upon first debate to fly to Europe, which Gilligan filled with an ad of him next to an empty podium. Next, Lindsay’s announced deal included massive giveaways for the growing economies of the G10, combining massive devaluation of the dollar with incentives for West Germany and Japan on a whole host of things. Gilligan haughtily referred to these trade deals as “Lindsay’s thirty pieces of silver,” which he received a bit of mockery for, but the average blue-collar worker wasn’t laughing. German auto was already eating America’s lunch, and now John Lindsay was here practically begging GM to declare bankruptcy! The textile plants left in the south were keeping much of the local economy going after so much social turmoil, and giving that away to Japan might as well be a death blow! While the union leaders loved Gilligan from the get-go, the blue collar rank-and-file that were the New Deal Coalition started joining their kids as Gilligan made more sense. Finally, Lindsay had been premature in his announcement, eager to hit prime time in America to salvage the situation, and he didn’t realize how furious his negotiating partners were with his taking credit before anything was officially written down, leading to the French, West German, Japanese, and Italian delegations going home later that day. The next morning, Americans awoke to learn that the deal was dead.

A rescheduled debate two weeks before voting went predictably horribly for Lindsay, who tried to stick to the script but sounded hollow as he reiterated the administration’s successes given his failure. Gilligan preached exactly how his economic stimulus plan was designed to not sell America’s economic competitiveness down the river to save finance, and the average middle-class voter who liked Kuchel but was scared of this recession was paying attention. The talk of reckless moves on civil rights, the supposed radicalism of his campaign in supposed associations with Cesar Chavez and Bobby Seale and Michael Harrington, it didn’t matter to anyone who didn’t have enough money to think about those kinds of things. The economy was falling apart, and only one candidate seemed poised to pull America out of this mess better than ever.

The ensuing party at Gilligan’s headquarters was the stuff of legends, the political version of the Longleat festival. Though so much looked bleak, for once the younger generation felt in control of their destiny, that they had something to believe in. Jack Gilligan himself didn’t have time to partake in the festivities, though. Even as TIME proclaimed Gilligan its person of the year with a cartoon of him donning FDR’s glasses and pipe, Gilligan’s longtime friend, in-house economist for Americans for Democratic Action, and Secretary of the Treasury-designate John Kenneth Galbraith shuttle-hopped his way across Europe, making clear his boss’ intentions and practically begging a second G10 summit to truly resolve the issue. Kuchel and Gilligan’s Oval Office meeting went well enough, though the former was clearly a bit grumpy over rebukes of his slow-and-steady approach by the impatient President-Elect. By the time of the inauguration, the Gilligan administration already had a summit at Camp David planned and a relief package practically drafted by Galbraith.

The stimulus bill, born completely of Galbraithian dirty Keynesianism, was a bundle of sticks for the G10 with a brief offering. Wage and price controls, authorized by the act, were to be implemented immediately, and the glut of funding towards infrastructure, government programs, and investments in the very American industries Lindsay had been accused of selling out was praised as a speedy reaction. Internationally, it ordered the temporary floating of the dollar from the gold standard and moderate devaluation of the dollar, meeting some of the core demands of the moment to prove the administration’s seriousness. Memorably, Galbraith himself called the administration approach to the international system “everyone needs to eat their vegetables,” setting the tone for the G10 leaders’ arrival that May.

*****

John Hansan hated this part of his job. Jack was a good man, someone who believed in what was right and would grab the bull by the horns to get it, and hell, Hanson admired his friend for that. He was willing to break a few dozen eggs if it made things better. But when you’re the arrogant son-of-a-bitch’s Chief of Staff, and the entire global economy rests on keeping him from running his mouth… it was tiring. Fucking exhausting, even. He preferred those moments in the Oval when it was just them, where he didn’t have to worry about keeping Jack in check and the loose cannon could just let loose on whoever wasn’t in the room. But that wasn’t the job right now. As it stood, Jack Gilligan was puffing up, beet-faced as always when launching into one of his sermons. The Germans were talking about more favorable trade terms, about market liberalization, and Chancellor Strauss had gone and made the mistake of mentioning BMW. Hanson had to stifle a groan at that one, and he could see Canadian Prime Minister Robert Stanfield shuffling uncomfortably in his chair.

“Is that what this is about? Some jobs for your hometown and money for your friends in Munich? You might as well cut my balls off right here and present them to the assembled press outside, Chancellor. We’ve given you a lot of ground here, hell we’ll do another round of devaluation, but you can’t seriously be thinking that we’re going to just give away the crowning achievement of American industry. If that’s the breaking point, then dammit we might be done-”

“Mr. President, you have an urgent message from Treasury. Galbraith’s got updated projections from yesterday’s discussion.” An aide burst in and interjected, slicing a white-hot knife through the growing tension exuding from the surly Bavarian across from his boss. Hansan smiled to himself as he knew those non-urgent projections had been ready for an hour. That defusing trick had worked too many times to count.

“Yes, very well, this’ll just be a moment.” Both the President and Hansan stood and walked outside the Camp David cabin they had been in.

“Can I speak candidly, Jack?” Hansan asked as Gilligan read the message.

“Get on with it.” Gilligan scowled.

“We were about to kill the negotiations again, I could see it. Strauss was about to leave and he was definitely going to take Tanaka with him-”

“To hell with them all, John! If they can’t see that I’m in office because the American people rejected their… their… their EXTORTION” - to which the President punctuated with a jab of his index finger into Hansan’s chest - “then I don’t know if we can save this!”

“You’re right we can’t give those jobs up, but we won’t get anything done at home if we can’t fix this mess first. Mark [Shields] was showing me the polling this whiz kid named Pat Caddell ran for us. People are disaffected, his words, and they need to see decisive action from us to trust that things are working. We lose all credibility if this fails.”

Some of the ruddiness faded from Gilligan’s complexion as he talked. It was how Hansan had survived all of those years, after all. “We’re fucked either way, aren’t we John?”

“Not necessarily.” Hansan cut it short, once the President was prompted it was better to let him figure it out on his own. Gilligan was clearly mulling it over in his head anyways.

“We need a new angle, that’s the only way out of this. Think Warnke” - by this he meant their pitbull of a Secretary of Defense - “could drum up some numbers on NATO spending, see if we could redirect some of the money from those useless projects Kuchel handed out like candy to our defense contractors? Christ, Lockheed’s basically got Strauss and Tanaka on their payroll” - to this he let out a low, harsh laugh - “I’m sure they’d be all over the chance to grease the wheels a bit more. Mitterrand wouldn’t mind either, I’m sure.”

Hansan straightened his tie. “I’ll call the Pentagon, see what they can do.” Gilligan simply nodded and walked back in.

*****

After nine days of talks, a framework for the rebuilding of the international economy was created by the Camp David Agreement, wherein all parties agreed principally to the transition to a floating currency regime. Gilligan’s proclamation that “let me be clear: what we have done here today will not cost a single American job” earned accolades given the memories of the failed round in Brussels months prior. Though much of the western world remained mired in varying degrees of recession - with America most badly hit - the situation was seemingly resolved, and the gold standard for international currency dead.

Gilligan could finally turn his eye to domestic reforms, something the Democratic majorities in Congress at last seemed receptive to. Throughout the Kuchel years, the old segregationists had simply aged out of office - men like Strom Thurmond and James Eastland passed away throughout his term, and the ensuing vacancies made ideal opportunities for the New Southerners. In his unlikely campaign for the open seat, future Senator Cliff Finch summarized the dynamics of the generational turnover best after being accused of unserious behavior by roaring "If they call you rednecks, clowns, or whatever, then I'm proud to be one!" Similar populist antics crested throughout the region, with Jimmy Carter ally Zell Miller and anti-Wallace Alabaman Al Brewer taking their seats as Richard Russell and Lister Hill left office in caskets. By the time Jack Gilligan was in office, Majority Leader Hubert Humphrey - long a bête noire of the segregationists - had built enough relationships with freshman southerners more concerned with diverting stimulus money to their constituents than anything else. Humphrey may not have had LBJ’s ability to speak to their culture, but he could speak pork. While turnover in the House was much smaller simply due to the lower median age of the southern incumbents, Speaker Boggs’ conciliatory, consensus-driven approach to liberal politics continually helped to mollify them, even if the House proved to be the more difficult of the two bodies to push things through.

Congress had its own machinations in mind before working on Gilligan’s pet issues. First came a longer-standing desire of its social-democratic wing. A number of significant reforms to the American government had been tinkered with on their side of politics, though failing to gain significant traction within the ideological consensus of the past two decades. One man had kept the movement for constitutional review on life support: Birch Bayh of Indiana. Running the Subcommittee on Constitutional Amendments, Bayh had brought in countless legal scholars to determine what was most viable, hoping to do to the Constitution what had seemed denied by the federal electoral process. Bayh’s failed bid for the nomination in 1972 regardless, his relentless lobbying at that year’s DNC saw the party offer a very Stevensonian theoretical endorsement of “review of our Constitution and appropriate amendments aimed at the modernization of our government” that the Gilligan campaign specified into a “Bicentennial Review” four years later. Come 1977, Bayh wanted to act, and Jack Gilligan couldn’t agree more.

In the end, three amendments received a vote. First, a relatively non-controversial procedural reform on the presidential succession was drafted, wherein the president would have the power to appoint a new vice president via Senate confirmation in the event of a vacancy, as well as codifying that presidential succession would flow through the cabinet secretaries in the event that there was no president or vice president. Then came the DC Home Rule Amendment, a similarly bipartisan proposal which turned over self-government in its entirety to the federal district and provided it with congressional representation equal to the smallest state. Finally was the Civil Rights Amendment. A modification of the Equal Rights Amendment proposal that had failed under Kuchel in 1970, this was, unbelievably, a compromise with the south during the platform negotiations - Gilligan had endorsed a new civil rights bill to supplement the 1969 bill, but when Long and Boggs demanded that be tamped down on he counter-offered an amendment as a compromise. The logic was that the federal party would be seen as less totally responsible to local constituents, it met the mantra of “states’ rights,” and it was implicitly easier to beat. It was just one simple sentence: “No political, civil, or legal disabilities or inequalities on account of race, color, religion, sex, and national origin shall exist within the United States or any territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” This was the narrowest of the bunch, yet it still saw significant cross-party approval as it even forced the Goldwaterites to eat their usual words where they theoretically supported civil rights but doubted the constitutionality of whatever proposal was being debated that day. Gilligan had naturally endorsed all three proposals, but observers noted the slight displeasure in being asked about those renovations instead of his own work, the way he pursed his lips ever so slightly and seemed to pinken just a little bit when talking about the “great work done by Senators Bayh and Humphrey to make a more perfect union.” Indeed, Gilligan was legendarily self-assured to the point of arrogance, creating a sort of moral impatience in every discussion he had about policy. Though Humphrey pleaded with him that this was how Washington works and Speaker Boggs demanded more time to whip Dixie into shape by “starting off slow with [the amendments],” President Gilligan’s certainty in his own righteousness chafed against their sensibilities and drove him to consider what could come next.

Seeking to flex his own mandate instead of voicing support for Congress’ machinations, Gilligan leapt directly into one of the greatest political footballs of the past two decades. In a highly publicized address from the South Lawn, President Gilligan announced his support for a major slate of electoral reforms. Elections had long been a decentralized process in the United States, and a voting reform bill had long been a demand of the civil rights crowd. Gilligan wholeheartedly agreed: “ever since the days of Thomas Jefferson, the Democratic Party’s aim has been to let the people rule. What I’m proposing is nothing less than the realization of that goal of our Founding Fathers.” The Gilligan proposal as submitted to Congress was a radical step in line with this. It mandated the lowering of the voting age to 18 nationally, the implementation of same-day registration, the creation of Election Day as a federal holiday, stringent campaign finance regulations, a ban on poll taxes, some sly amendments to the Civil Rights Act of 1969 to give the Department of Justice more teeth in enforcing discrimination cases, the withholding of federal elections funding from states who did not comply with these provisions, and a Federal Elections Agency given power to oversee the implementation of all of this. Privately, Gilligan also voiced his support for the abolition of the electoral college, quipping “what’s one more amendment?” but that proposal was quickly scrapped in the early negotiations due to lacking support from within the Democratic caucus.

Gilligan’s proposal set off a firestorm in Congress. Old segregationists saw it as the death of their power, and they fought tooth and nail to strip out any serious power to impact their elections. More moderate southerners were hesitant as well, many of them not personally opposed but worried about how their constituents would react and too unsure in their power to yet cast such a vote. They wanted something they could talk about back home, and this bill wasn’t it no matter how much easier it also made it for the rednecks to vote too. In response, Gilligan left Washington to tour the impacts of his stimulus bill. He went with local officials to tour oil rig construction in Texas, shipbuilding in Mississippi, thriving poultry farms in Arkansas, coal mines in Kentucky, a new NASA launch facility based in North Carolina’s research triangle, and a plethora of new bridges, railroads, and highways being administered under the new Department of Transportation. The message was crystal clear to all the south’s delegations as they saw Jack Gilligan speaking in their states: “I’ve given all of this to you, and I can keep it up if you give me what I want.” The Federal Elections and Campaigns Act broke through the Senate after 39 days of debate with not a vote to spare, after the President conceded that the first Supreme Court vacancy would be filled by a southerner. At last, equal voting rights before the law existed in America, even if voting rights litigation would occupy federal courts for the next decade.

As if by fate, Supreme Court Justice Tom Clark passed a mere two months after the passage of the FECA, just as 1978 began. True to his word, Gilligan deliberated for a bit before settling on an unconventional choice: Georgia Chief Justice Phyllis Kravitch. She, like many others in the often-personalist Georgia political environment (a direct result of Jim Gray’s near-dictatorial hold on the state) was an ally of Jimmy Carter’s and a quietly liberal moderate. She seemed the best compromise between Gilligan’s tastes for a more supportive court and his debts to the south. Nominating the first woman to the Supreme Court and reviving the “Jewish seat” that seemed to have quietly died set off quite a bit of coverage, including glowing profiles of the new nominee. Kravitch’s performance in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee was practically a pre-emptive celebration. Even prominent Republicans spoke highly of her, with the arch-conservative Senate Minority Leader Roman Hruska praising her as “a true representative for average Americans… I’m glad President Gilligan made such a sensible choice instead of bending to his radical friends.” Quickly, Kravitch was confirmed, making her the first woman on the Supreme Court.

As winter gave way to spring in 1978, as the Presidential Succession Amendment was made the 24th, as Attorney General Terry Sanford brought more and more voting rights cases before the courts as perhaps the only man suited to do so without causing a southern revolt like that of 1948 or 1968, and as the administration geared up for its next major reform, nearly half a world away a deep boom reverberated from a small island off East Asia. As both American and Soviet satellite monitors picked up the telltale double flash, a mushroom cloud illuminated the heavens over the Straits, alarming citizens who could see it from both sides. Then, a few hours later, a state broadcast from President Chiang Wei-kuo crackled over the television and radio in Taiwan, announcing the nuclear test and taking credit for “the ensuring of the security of the Republic.”

The nuclearization of Taiwan was a bridge too far for the mainland. Chairman Lin immediately accused Washington of giving the nuclear warheads to them, of aiding the secret Taiwanese nuclear program. After all, the United States still recognized the Republic of China as the legitimate government of the nation, what reason did they have to not provide aid to Taiwan? The truth, naturally, was far more complex. The Kuchel administration had been providing copious military aid to Taiwan, and when an assassin’s bullets felled Chiang Kai-shek the Kuchel-era CIA engineered the rise of his adoptive son from the military to the presidency under the Eisenhower-era doctrine of “it doesn’t matter if they’re our S.O.B.s.” Officially, no nuclear sharing had occurred, though the United States had not yet ratified the Non-Proliferation Treaty due to opposition to Bill Fulbright’s dovishness. Unofficially, decades later, Ambassador Anna Chennault had served as a proxy for the dissemination of nuclear technologies in East Asia, aiding Taiwan with their issues with delivery mechanisms that plagued their secret program. The details didn’t matter, though - Beijing was convinced America was responsible for this, and they had an ultimatum: withdraw the warheads from Taiwan or we “denuclearize” the island.

Immediately, the administration saw itself enter into crisis mode. The United States entered DEFCON 2 as a nuclear war seemed imminent. This was no Israel - both sides had nuclear warheads, and both would be prepared to use them if the situation wasn’t defused. A Chinese blockade of Taiwan only exacerbated the situation, seemingly confirming the worst impulses of all actors. President Gilligan pulled together an emergency broadcast to the nation explaining what had happened and “our intent to pursue a peaceful resolution to avoid the very real possibility of a nuclear conflict,” his usual emotion replaced by a ghastly intensity that belied the seriousness of the situation. Panic set in amongst the populace as Americans rushed the grocery stores for bread, milk, and anything canned. The world looked on in horror as the doomsday clock went from minutes to seconds.

The White House seemed the epicenter of the storm. More broadly principled disarmers like Secretary of Defense Paul Warnke came into direct conflict with pragmatists like Secretary of State Harland Cleveland, and meanwhile the Joint Chiefs - represented by General John Hennessey, a man experienced himself in nuclear preparedness - seemed terrified of the prospect of losing military operations in Taiwan and what that would mean for all operations in Asia. Admiral Noel Gayler, the chief of USTDC in Taipei and a closet disarmer, only worsened the situation upon reporting back from an emergency meeting with President Chiang. Chiang was ardently opposed to giving up his nuclear warheads, believing them to be the only thing standing between Taiwan and annihilation. Not only did he reject Gayler’s overtures to the idea that the PRC would invade them for real if they didn’t concede, he implied that he would go public with Ambassador Chennault’s aid, fully knowing that it would render the situation unsalvageable and force the US to come to his defense. The situation seemed well and truly hopeless, and a near-skirmish between PRC and American ships saw one wary officer be the only line of defense between a first strike.

But the People’s Republic hardly wanted war either. Chairman Lin was always a reluctant leader, and his rehabilitation of Mao meant that many of his hardline allies stuck around. In particular, his wife Jiang Qing, a longtime Lin ally and Cultural Revolution leader, held significant sway over state decision-making. Jiang’s popularity with the CCP rank and file was never particularly high to begin with, but amidst the crisis, their dissatisfaction hit a fever pitch. Using a complex dance of trusted intermediaries from the Fulbright years, Harland Cleveland and Zhou Enlai were able to meet in Hanoi to discuss the matter face to face.

There, both diplomats came to understand one another’s desire for avoiding war: China could not suffer such a humiliation publicly, and America could not be seen abandoning its allies. The former needed to look like they won, and the latter needed to be able to explain away any concessions made by Taiwan as not stripping away an American ally’s right to defend itself. With this in mind, a resolution arrived soon after. Publicly, the United States would recognize China as the legitimate government of the mainland and China would withdraw the blockade, allowing Taiwan to maintain its nuclear arsenal. Privately, the United States also agreed to a two-year timetable for the withdrawal of all troops from Taiwan and the shuttering of USTDC. Though never agreed to, privately Beijing saw to it that Jiang Qing was dragged out of power, placing Zhou and his allies “the three Hus” - Yaobang, Keshi, and Qili - as the strongest clique in Lin Biao’s inner circle. Celebration filled the streets as President Gilligan addressed the nation, announcing the end of the crisis even as Chiang fumed, knowing he’d effectively become a rogue state in the western bloc.

In the immediate aftermath of the crisis, Gilligan’s approval rating leapt to 68%, mostly from a nation grateful to have not been subjected to armageddon. While his cool, collected leadership through the situation made great movie fodder years down the line, in the moment he was aching to capitalize on the rallying around the flag. As he jokingly put it too close to a microphone, “we never waste a good crisis around here.” Even as right-wingers feigned outrage at the comments, Gilligan set to work using the crisis to finally make the push prophesied by William F. Buckley: healthcare reform. The current proposal snaking its way through Congress was the Humphrey-Griffiths Bill. Named for two midwesterners of sterling social-democratic credentials, the proposal was as simple in aims as it was complicated in actuality. It was the merger of the wildly successful Eldercare and Childcare programs into a single “Medicare” system, one that amounted to a universal national health insurance plan in the United States. After all, its advocates reasoned, America already had government-funded healthcare for those under 18 and over 65, if those worked so well then it should apply to working people too.

The only flaw was Hubert Humphrey’s death. Humphrey had been suffering from bladder cancer since his diagnosis in 1973, the reason he had forfeited a bid for the White House in 1976 despite his intense desire to hold the office. He knew his time was limited, and after collapsing during floor debate on the healthcare bill he was rushed to Walter Reed, where he rapidly deteriorated and died the next day. All across the country, America’s politicians paid their respects to the “lion of the Senate,” a man not just known for his idealism but also his geniality and infectious personality. At his funeral, President Gilligan’s eulogy simply offered Humphrey’s own words, the words engraved on the memorial of him in Minneapolis: "It was once said that the moral test of Government is how that Government treats those who are in the dawn of life, the children; those who are in the twilight of life, the elderly; and those who are in the shadows of life, the sick, the needy and the handicapped. This is what Hubert Humphrey died fighting for.”

Gilligan’s citations of Humphrey’s words about how the government treats the sick and needy did not go unnoticed. Though new Senate Leader Russell Long had many more qualms with the idea of such a universal healthcare system, a flurry of White House pressure descended on him about supporting the president going into the midterms and about how the optics would look if the party couldn’t even deliver on Humphrey’s dream after he collapsed talking about it on the Senate floor. In the end, Long gave, but not without his pound of flesh, and the bill cleared both houses without a single Republican vote. Gilligan chose to sign the Humphrey-Griffiths Act with Muriel Humphrey by his side, a reminder of who wasn’t there to see it.

The lack of Republican votes belied a more interesting phenomenon. The party, fearing a new Roosevelt after 1976, quickly and desperately searched for a new line of common attack. They had settled on a crusade begun long before by Representative Howard Jarvis against taxation. Jarvis had proudly noted in his campaign fliers that he had “never voted for a single tax hike,” even when it was controversial like opposing the stimulus. The shlubby Jarvis had long been a laughingstock in Washington, but amongst conservative dissidents his talk of “King Pork,” the high spending by this administration, and the supposed high tax rates imposed by Gilligan - Christ, look at Medicare, that’s a black hole of money you’re not getting back, they’d say - hit a sweet spot. More and more Goldwaterites latched onto the anti-tax fervor, talking a big game about the Founders’ resistance to taxation without representation. When House Minority Leader Dick Obenshain, the highest-ranking Goldwaterite in the Republican Party, got up on his soapbox and pledged to cut down on the mass of wasteful spending to put that money back in Americans’ pockets, it was clear what tack they’d take for the midterms.

It almost worked, too. They broke the liberal majority in the House, whittling Speaker Boggs down forty seats to just 229. They flipped a handful of Senate seats on an otherwise bad map, at bare minimum dropping Russell Long’s caucus below 60 seats. This included a surprise victory in Texas for staunch Goldwaterite Hank Grover over Lyndon Johnson’s successor Walter Jenkins, aided in no small part by the Grover campaign outing Jenkins as a closet homosexual. Privately, John Hansan admitted that the national press that the Grover-Jenkins race earned scuttled plans for a federal law decriminalizing homosexuality after the midterms, disappointing gay activists who felt they had a more sympathetic president in Gilligan. It wasn’t just the number of victories, though - it was where they happened. Since the Baby Boom the south’s suburbs had been growing as out-of-staters moved into the areas around the big cities, and these migrants were often very conservative and less ancestrally Democratic than their more rural, traditional counterparts. Though Kuchel had failed to make inroads, the right-wingers’ ascendancy after his departure from office activated these otherwise apathetic voters, flipping a number of suburban districts from Atlanta to Houston blue for the first time. The New South seemed to have two faces to it.

The losses were far more devastating within the White House. Gilligan wouldn’t publicly admit it, but he was furious that the coalition that propelled him to the White House seemingly didn’t work. He had followed instructions, why, then, did he lose so much? In a White House often designed to insulate a volatile president as much as it was to function under him, his close-knit staff started to blame the very political staff that got him there. Under Hansan’s direction, Mark Shields, Peter Hart, and Bob Shrum cleared out their desks, and in their place came a veteran campaigner for the Gilligan operation, someone who’d had no problem reaching out to the youth in previous years: his daughter, Kathleen. Conservative columnists howled nepotism in the pages of the National Review, but Kathleen was reliable. She was someone Gilligan would trust, who wouldn’t blow the whole thing the way all of his “one-hit wonders” did.

Regardless of the change in direction in the political staff and the “Thanksgiving Massacre,” as some dubbed the massive staff change, the Gilligan White House soldiered on. In his State of the Union that year, Gilligan indicated his next targets: labor and education. The latter was far easier to approach, as Gilligan simply wanted a greater expansion of the HEA. His vision was not a total system of university merit as Bill Fulbright saw, but one where everyone who wanted could obtain higher education. As such, the Higher Education Act Amendments of 1979 were born, a smorgasbord of funding increases, the creation of a federal Department of Education split from the Department of Welfare, and the shifting of the distribution model to provide Fulbright funds more directly to state universities, community colleges, and vocational schools. Though tuition was by no means free - a compromise made with more liberal Republicans - the funding model set up by the amendments cut costs significantly for working and middle class Americans. Labor law was far more difficult. Though the minimum wage had been raised in 1977 to some fanfare, Gilligan’s Secretary of Labor Bill Kircher was a longstanding ally of the UFW, and a priority of both his and Gilligan’s was fairer working conditions for Bracero workers. A law intending to modify the program reinstated by Kuchel to provide equal work protections set off a far larger mess than expected in Congress as even moderate Republicans and southern Democrats raised opposition, finding the proposal objectionable at best and dangerous to the system of farm work. Representative Raul Hector Castro’s bill quickly died over a staggeringly large vote-down by both southern Democrats and virtually all Republicans, dealing an embarrassing blow to Gilligan and proving the difficulty of domestic reform going ahead. Apart from the nomination of a successor for the retired Justice Walter V. Schaefer - Frances Farenthold, a Texan judge propelled upwards by Lyndon Johnson - Gilligan had little to do at home.

The White House’s response was that Jack Gilligan ought to go look magnanimous elsewhere, and where better after the Braceros than Latin America? After all, Latin America had suffered mightily over the past two decades under CIA meddling and various military coups. Chile fell to an impeachment of Salvador Allende followed by a deeply rigged election all stage-managed from Langley, a pro-American coup in Panama designed to clamp down on the failure of the Canal Treaty went sideways quickly, and no shortage of other efforts to stop Soviet influence had proliferated throughout the continent. The result was a mess of distrust and instability that Gilligan could not abide by, true Stevensonian that he was. So, as the State Department worked to assure stability whether it be by renegotiating international debt in Latin America or withdrawing tacit support for regimes like that of Anastasio Somoza Debayle and, Pope Martin VI (formerly Argentina’s Eduardo Francisco Pironio until his election in 1980) became perhaps the only public critic who dictators like his homeland's José López Rega could not ignore or imprison, new democracies sprung up throughout the OAS, and Gilligan intended to show his gratitude. Gilligan’s tour saw him given a hero’s welcome, his Catholic faith a unifier with many of the people of the region and in meetings that included Mexico’s Carlos A. Madrazo, Brazil’s Leonel Brizola, and even new revolutionary governments like Nicaragua’s Carlos Fonseca Amador. Given a brief respite to look like a statesman and to forget about Congress, Gilligan’s talk of a new Pan-American ideal - even ensured by simple moves like issuing official recognition of the Pan-American Highway within the United States - reverberated throughout the continent’s returning democracies.

Not all was well abroad for the administration in its lull with Congress. If South America was becoming more vibrant, southern Africa was a much larger headache. Though the fighting in the Democratic Republic of Congo had finally ended with the fall of Léopoldville in 1975, ensuring Patrice Lumumba’s total control over the country, Angola was another story. Angola had largely fallen to the communist MPLA except for Holden Roberto’s strange mishmash of tradition and cronyism in Kongo (not to be confused with the Republic of Congo or the Democratic Republic of Congo), and Jonas Savimbi had responded by turning to more unsavory allies - South Africa and Rhodesia in particular. Though the latter was engaged in its own complex war for survival against all its neighbors and a furious new Prime Minister Peter Shore in London, they were still all too willing to lend arms and funds to Savimbi to stick a thorn in their enemy’s eye. South Africa had only grown more radical, finding the declaration of an “Era of Rising Standards” to mean an assault on their way of life and seeing the increasingly large Soviet checks given to the SACP. They were all too happy to join the fight in Angola. Meanwhile, Lumumba was willing to lend his own support to the MPLA, more out of fury towards the settler-colonialist intervention from the south than anything. Angola had quickly become a complex web of proxy wars, with South Africans with Rhodesian guns confronting DRC troops and their shipments of the infamous “Andropovka” (a state-run consumer vodka created by the leader of the same name). The American government quickly developed a migraine just looking at the situation, and their public call for a global suspension of all military aid to Savimbi and South Africa only bonded the two closer together. The Angolan mess surely wasn’t going away anytime soon.

That quickly took a backseat to the Gilligan administration, though, as 1979 turned to 1980 and led to election season. For the Republicans, it seemed at first that there were few willing candidates, with only Representative Jarvis and Senator Dole in the race in any meaningful capacity. Then the race was upended by a remnant from primaries past: Barry Goldwater. The prickly conservative icon had returned in 1970 with a successful run for the governorship of Arizona (privately tired of national politicking given his losses in those areas in quick succession), taking over from Stewart Udall and driving Arizona to the right. He had never lost his star power with the right-wing grassroots, and now here he was able to talk about what Goldwater in the big chair would look like because he’d done it! Quickly, he surged to the front of the pack - time heals all wounds, including those Goldwater inflicted on many a campaign staffer in the 60s - and never looked back, not even when Tommy Kuchel hopped from retirement to endorse late entrant Pennsylvania Senator Ray Shafer for the nomination instead, warning against the capture of the party by Goldwater once more. Paradoxically, this only made Goldwater more popular with the right-wing base, the people who were reluctant with Kuchel and despised Gilligan’s total upending of the America they wanted, and he never looked back. It seemed that both nominations would be coronations, battles of the ideological tendency of both parties. It was the type of matchup that horse-race journalists salivated over, the Old America versus the New America.

At first, it seemed the Old might finally be able to pull it off. While the economy had finally begun to rebound, many of Gilligan’s changes had been too much to swallow for the white suburbanites, the people who made up the natural electorate for Goldwaterites. The first shock to the race came when, in a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court elected to uphold the Humphrey-Griffiths Act, with Justices William Brennan, Cyrus Vance, William Rogers, Phyllis Kravitch, and Frances Farenthold in the majority. The closeness of the decision infuriated Goldwater, who called for “an immediate lowering of the obscene tax rates needed to fund this monstrosity” and pointed to his own severe property tax cuts in Arizona. Matters were made worse when Gilligan visited a sheep farm in Missouri, joking to the farmers “I don’t shear sheep, I shear taxpayers.” Those words were plastered all across Goldwater ads for the duration of the campaign as a sign of his apparent disdain for the people.

Midway through August, noticing Goldwater closing in, Kathleen Gilligan began to truly reach out to the student organizations once more. Their work in 1976 had delivered Gilligan, and Goldwater was as much a villain to even the older activists as any. Their work injected new life into the campaign, taking the lackluster messaging of the White House and supplanting it with major attacks on Goldwater. Goldwater was a dinosaur, someone who’d sold off the entire state of Arizona to its biggest corporations, and no doubt he’d do the same to America. The AFL-CIO, now fully dominated by reformists like Eddie Sadlowski, Jock Yablonski, Tony Mazzocchi, and Thomas Donahue, poured all it could into salvaging the campaign, portraying Gilligan as a pro-labor president who cared about American jobs instead of selling off the family jewels like Goldwater. Two debates between Gilligan and Goldwater were contested, with the former held to a draw with a clearly unprepared Gilligan and the latter a decisive victory for the President, who memorably quipped that “we don’t run on horse and buggy anymore, Governor” in response to a muddled Goldwaterism about the bloat in pork disguised as military spending over the past hundred years. Though Gilligan no longer seemed like the fighter he was in 1976 or even 1978, the rebuilding of his organization in time for the election by his daughter and a small quiet Gilligan vote amongst southern white populists who saw their community’s revitalization as more important sealed the deal.

*****

Kathleen Gilligan was on top of the world.

It was easy to say that in Washington and then lose it all, so most folks didn’t. It was a bit like saying Macbeth in a theater. But here she felt she could finally think it. Why wouldn’t she? She got a glowing profile in the Washington Post - for heaven’s sake, the Post! - about her efforts to revive a stalled-out Gilligan campaign. She was being courted by Democrats around the nation, seen as the genius behind the throne - literally after she sat damn near right behind her father at his second inaugural. She had an office for “political operations” in the White House, was invited to practically every other major meeting - over John Hansan’s objections - and to top it all off she was a shoo-in for virtually any office she wanted after the term ended. She was on top of the world.

And then there was the ceremony now. It was one to honor her, in a way, an affair in the White House so grand because one hadn’t been seen in ages there. It was just for her and one of the other campaign miracle-makers, the young Arkansan ex-representative who ran the campaign in “redneck country,” as he often put it with an exaggerated drawl in their Cincinnati offices. Even something that stupid made her laugh a bit.

Her father was there too, beaming, taking time away from his job to see the grand strategist of his own bloodline celebrated. Sure, the Republicans complained about the wasteful spending in it all - they always did. She bet it was Dick Obenshain up to it, the insufferable ass. No matter, though. The President of the United States walked her up to the front himself, and it was hard for her not to tear up a bit. She blinked and realized she had lost focus at the most important moment.

“I do.” She said, looking at the young man across from her.

“William Jefferson Clinton, do you take Kathleen Gilligan-”

“I do.” He cut off the line with a sly grin, and it was official.

*****

The second term wasn’t all just White House weddings, though. A shock came when Yuri Andropov passed away that February, leading to a messy succession wherein the party elder Nikolai Tikhonov emerged a toothless General Secretary but cosmonaut-turned-politician Valentina Tereshkova asserted her reformist bloc’s influence in the Politburo, leading international observers to take notice of her. Then, Prime Minister Enrico Berlinguer’s Eurocommunist experiment - elected in 1978 over the worsening economic and social crisis of the Years of Lead - saw an increasing political deadlock between the PCI-controlled Chamber of Deputies and the coalition Senate end with President Giovanni Leone ordering his dismissal and appointing Count Edgardo Sogno Prime Minister in his place. The golpe bianco effectively ended the “First Republic” and led to a number of constitutional reforms towards a semi-presidential “Second Republic” directly inspired by de Gaulle, whom Sogno was a heavy admirer of. Later, it was revealed that Berlinguer’s overthrow was based on two panics. First was the CIA, whose NATO stay-behind operations had dominated Italian politics. Upon their suspicion that Berlinguer intended to publicly reveal Operation Gladio’s existence, only heightened after PCI bank nationalization kicked a hornet's nest of corruption that was implicitly linked to them, they decided self-preservation was more important than waiting for orders from Langley and leapt into action (though some theorize that CIA Director Charlie Wilson and President Gilligan were aware and even supportive of the move). Second was President Leone, who had been implicated in the Lockheed bribery charges that had toppled Franz-Josef Strauss in West Germany and Kakuei Tanaka in Japan and was now in a fight to avoid conviction. Regardless of the rationale, the PCI and MSI were swiftly banned by the new government, and Sogno consolidated under a new constitution even as outrage filled the streets and militants brawled with police.

But this was small potatoes compared to the Middle East. In April 1981, though, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia awoke to Mecca burning as protesters led by Juhayman al-Otaybi seized the Grand Mosque of Mecca, demanding a bevy of unreasonable goals for the fundamentalist cult surrounding al-Otaybi. The Kingdom had grown repressive as it ossified under King Faisal’s increasingly-doddering and often corrupt quasi-constitutionalist rule, with a public feeling that he spent more time modernizing to make nice with the West than caring about their suffering. The people simply needed an inflection point after years of an economic slump, and watching the military move in on the Grand Mosque was too much to bear. After a massive crowd of Meccans confronted the military, a skirmish started between them and French Foreign Legionnaires working with the Saudi government. Though al-Otaybi and his followers died, protests sprung up across Saudi Arabia, bringing the country to its knees as thousands swarmed every city. The House of Saud elected to stay at first, but then a young princeling named Faisal bin Musaid al-Saud saw the moment as the perfect time to dispose of the old king, who he hated for cutting his allowances. So, as the King left for his plane with members of his family, the spoiled nephew pulled a revolver and shot him five times before being subdued. Images of King Faisal’s dead body were jet fuel for the protests, who not only saw the elderly Westernizer dead but a vacuum to fill. His immediate family began to flee to the United Arab Emirates, leaving behind an uncertain fate.

The Saudis falling sent shockwaves through the oil market. Gas prices spiraled in the United States amidst the uncertainty. Gilligan called a special session of Congress to ask for authorization for controls and rationing as well as a federal Department of Energy to coordinate the response, something he was granted within the next few days. The southern economy, which already rested on subsidized oil to a ridiculous extent, saw massive booms amidst the immediate price-gouging, an issue that would have to be resolved in the near future. But Jack Gilligan wouldn’t be the one to do it.

Jack Gilligan’s tone about taxation and government growth was especially infuriating to a certain subsect of radicals who subscribed to the Christian Identity, a white nationalist interpretation of Christianity popular among the far-right fringe that reads the Aryan race as the natural successors of the ancient Israelites. One of these disciples was Richard Snell, a militiaman and drifter who had previously contemplated half a dozen terrorist acts and assassinations, been in and out of the Elohim City Christian Identity compound in Oklahoma, as well as been a frequent visitor to Richard Girnt Butler’s “Aryan Nations World Congress” in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. During one of his stints in Elohim City, Snell learned that President Gilligan would be visiting New Orleans to meet with the state government to discuss becoming the 38th ratification for the Civil Rights Amendment. Furious in general, an unstable Snell hopped in an Elohim City truck to drive his way to New Orleans. Gilligan, who always believed in meeting with the people where he went, made no exception for this trip as he walked the French Quarter with his daughter and Governor Moon Landrieu. Richard Snell emerged from the crowd as the President’s troupe approached and fired three times. The first shot hit a building, the second grazed Kathleen’s arm, and the third landed fatally in the President’s chest.

Jack Gilligan’s legacy is that of a giant of American history. Most rank him highly among the presidents - generally, the only ones who consistently outrank him are Lincoln, Washington, both Roosevelts, and Eisenhower. Though liberals cheer and conservatives sneer at much of what he actually did, he remains responsible for a paradigm shift nonetheless. His response to the 1976 crash is given high marks on its own. A level-headed handling of the Taiwan Straits Crisis is nothing to be scoffed at, especially once the revelation of just how close the world was to nuclear war came out. Three constitutional amendments were passed with his direction; Louisiana voted to ratify the CRA as the 26th Amendment in mourning. Medicare remains one of the most popular government programs in America, with privatization a fringe position. Finally, his work on finishing the job on civil rights as the penultimate president of an era beginning with Harry Truman is perhaps his most enduring legacy, though he often shares that distinction with Thomas Kuchel. Most of all, though, an entire generation remains touched by the man they supported in their youth as the face of hope for a better society. The image of Jack Gilligan seems synonymous to most with one of a brighter future, and his daughter hunched over him as he lay dying remains one of the most poignant scenes of tragedy in American history.

Last edited: