Typo corrected.Alternate transliterations? Typo? Sound shift in a combining form?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Nobunaga’s Ambition Realized: Dawn of a New Rising Sun

- Thread starter Ambassador Huntsman

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 150 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 131: Daijo-daijin Nobuie and a 17th Century Retrospective Map of Daimyo 1697 Chapter 132: Food, Fashion, and Popular Leisure in Late 17th Century Japan Chapter 133: Yongwu and his Neighbors Chapter 134: Rise of the Gekijo - Music and Theater In 17th Century Japan Chapter 135: Upheavals in English North America Chapter 136: Early Days of the Era of Nobuie Chapter 137: Dutch or FrenchMarriage is indeed the only way of having an Oda emperor. The clans can fight over the shogunate, but the tennoheika is basically untouchable - a coup is an excellent way to lose all legitimacy in the eyes of the country (and possibly the clan).

Quick question, will the Oda clan ever usurp the chrysanthemum throne or will they just continue to marry oda members to the imperial family?

The latter. The emperor had been a ceremonial monarch for the most part since the Heian period with the exception of Emperor Go-Daigo during his Kenmu Restoration in 1333 so the imperial court poses no threat to the Oda clan. The Oda is comfortable with arranging powerful marriages with the imperial family and high-ranking noble families as well as co-opting the Konoe as a cadet branch of the Oda.

It's said that Oda Nobunaga saw himself as a god and possibly harbored ambitions to dismantle the imperial system. Although he's the closest to someone who not only couldve but possibly would've if he so desired, the course this TL took is based on the conclusion that that was certainly not going to occur under almost every realistic scenario.

It's said that Oda Nobunaga saw himself as a god and possibly harbored ambitions to dismantle the imperial system. Although he's the closest to someone who not only couldve but possibly would've if he so desired, the course this TL took is based on the conclusion that that was certainly not going to occur under almost every realistic scenario.

Chapter 63: Domestic Disruptions under the Zhenchun Emperor

Chapter 63: Domestic Disruptions under the Zhenchun Emperor

The reign of the Ming Emperor Zhenchun was one of trials and tribulations both externally and internally. The first half of his reign witnessed the sunset and inevitable decline of Jurchen power, particularly after the death of Nurhaci. This meant that throughout his tenure as emperor, Zhenchun was never worried about the northern frontier unlike so many of his predecessors. At the same time, Ming foreign policy began to shift attention to the east and south due largely to Japanese activity in Southeast Asia and the South China Sea, through both its trade expansionism and its war against the Spanish and Portuguese. At one point, through the return of Macau, Japan took complete control over all trade interactions between Europe and Ming China. Japanese merchants began to charge higher prices for European goods and constricted silver imports from the Spanish. Although Japan had been the predominant source of silver for Ming China in the 16th century, the supply began to deplete heavily at the dawn of the 17th century and Spanish silver from the Americas took over as the primary source of the prized metal. Because the stability of China’s currency relied so much on these imports, the constriction of Spanish silver negatively affected the Ming economy.

The constriction of the silver flow in 1633 compounded the domestic troubles of the Ming imperial court. Emperor Zhenchun’s reign was marked by serious challenges at home despite his relative competence. Shortly after his ascension, Zhenchun immediately faced opposition in the form of the Donglin movement. Formed around the revival of the Confucian Donglin Academy by Grand Secretary Gu Xianchang in 1604, the movement included many former bureaucrats who were in favor of Emperor Wanli’s eldest son, Zhu Changluo succeeding his father before the prince was executed during Consort Gong’s attempted coup in 1605. They had viewed Wanli as an irresponsible ruler and sought the elevation of a “Confucian gentleman” to the throne. However, when Zhenchun quickly proved to be a skilled, attentive sovereign, the Donglin movement began to fray as many switched sides and accepted the emperor as the “correct” ruler. Those remaining, including the activist Yang Lian, became implicated in a rumored plot to install Zhu Changluo’s surviving 19 year old son, Zhu Youxiao [1], to the throne and were executed in 1624. The Donglin scholars who had chosen in the beginning to work in the new emperor’s bureaucracy would go on to influence certain policies, including the decrease of arbitrary taxation of merchants [2].

Even with competent governance, however, Ming China would experience internal turmoil made inevitable by both the poor legacy of the previous emperor and climate change brought upon by the “Little Ice Age”. An early sign of this was the She-An Rebellion, sparked by heavy taxation in Sichuan province in response to Jurchen incursions from the north. When aboriginal chieftain She Chongming’s soldiers and non-grain supplies in place of the grain tax was presented at Chongqing and refused, the former rebelled and proclaimed the Kingdom of Shu. Another chieftain, An Bangyan, followed suit and soon Sichuan and Guizhou were being occupied by 300,000 tribal warriors. Despite the size of the rebellion, Ming victories against Nurhaci allowed Emperor Zhenchun to divert 200,000 well-supplied soldiers from the north to deal with the rebellion and both chieftains were summarily defeated by 1625, although bands of rebels continued to harass the Ming for years to come [3]. The war, however, would ultimately drain the imperial treasury of 17.5 million taels of silver. The troubles continued when in 1627, a severe drought afflicted the province of Shaanxi so badly some turned to cannibalism, with the provinces of Shanxi and Henan also badly hit by natural disasters and famines. These events would trigger multiple peasant rebellions in Shaanxi and despite the best efforts of the emperor, there wasn’t enough in the treasury to address everything quickly, and by 1631 well more than 100,000 rebels were operating in the area. These rebels were led by bandit leaders like Wang Jiayin, Zhang Xianzhong, and Gao Yingxiang. Initially, veteran anti-rebel leader Yang He was appointed to take charge of the situation, but his policy of amnesty for peasants who surrendered failed and was eventually dismissed over his ineffectiveness. The next imperial commander, Hong Chengchou, swung to the other extreme of the pendulum and acted too indiscriminately, killing civilians and rebels alike. It took a third individual, Chen Qiyu, to get the situation under control even as the uprisings spread to Sichuan but eventually in 1633, the rebel leaders surrendered and were allowed to go home with supervision [4]. Despite the end to the massive rebellions, portions of China were devastated and depopulated with pockets of dissent still burning hot and the imperial treasury was nearly empty.

The constriction of the silver flow in 1633 compounded the domestic troubles of the Ming imperial court. Emperor Zhenchun’s reign was marked by serious challenges at home despite his relative competence. Shortly after his ascension, Zhenchun immediately faced opposition in the form of the Donglin movement. Formed around the revival of the Confucian Donglin Academy by Grand Secretary Gu Xianchang in 1604, the movement included many former bureaucrats who were in favor of Emperor Wanli’s eldest son, Zhu Changluo succeeding his father before the prince was executed during Consort Gong’s attempted coup in 1605. They had viewed Wanli as an irresponsible ruler and sought the elevation of a “Confucian gentleman” to the throne. However, when Zhenchun quickly proved to be a skilled, attentive sovereign, the Donglin movement began to fray as many switched sides and accepted the emperor as the “correct” ruler. Those remaining, including the activist Yang Lian, became implicated in a rumored plot to install Zhu Changluo’s surviving 19 year old son, Zhu Youxiao [1], to the throne and were executed in 1624. The Donglin scholars who had chosen in the beginning to work in the new emperor’s bureaucracy would go on to influence certain policies, including the decrease of arbitrary taxation of merchants [2].

Even with competent governance, however, Ming China would experience internal turmoil made inevitable by both the poor legacy of the previous emperor and climate change brought upon by the “Little Ice Age”. An early sign of this was the She-An Rebellion, sparked by heavy taxation in Sichuan province in response to Jurchen incursions from the north. When aboriginal chieftain She Chongming’s soldiers and non-grain supplies in place of the grain tax was presented at Chongqing and refused, the former rebelled and proclaimed the Kingdom of Shu. Another chieftain, An Bangyan, followed suit and soon Sichuan and Guizhou were being occupied by 300,000 tribal warriors. Despite the size of the rebellion, Ming victories against Nurhaci allowed Emperor Zhenchun to divert 200,000 well-supplied soldiers from the north to deal with the rebellion and both chieftains were summarily defeated by 1625, although bands of rebels continued to harass the Ming for years to come [3]. The war, however, would ultimately drain the imperial treasury of 17.5 million taels of silver. The troubles continued when in 1627, a severe drought afflicted the province of Shaanxi so badly some turned to cannibalism, with the provinces of Shanxi and Henan also badly hit by natural disasters and famines. These events would trigger multiple peasant rebellions in Shaanxi and despite the best efforts of the emperor, there wasn’t enough in the treasury to address everything quickly, and by 1631 well more than 100,000 rebels were operating in the area. These rebels were led by bandit leaders like Wang Jiayin, Zhang Xianzhong, and Gao Yingxiang. Initially, veteran anti-rebel leader Yang He was appointed to take charge of the situation, but his policy of amnesty for peasants who surrendered failed and was eventually dismissed over his ineffectiveness. The next imperial commander, Hong Chengchou, swung to the other extreme of the pendulum and acted too indiscriminately, killing civilians and rebels alike. It took a third individual, Chen Qiyu, to get the situation under control even as the uprisings spread to Sichuan but eventually in 1633, the rebel leaders surrendered and were allowed to go home with supervision [4]. Despite the end to the massive rebellions, portions of China were devastated and depopulated with pockets of dissent still burning hot and the imperial treasury was nearly empty.

Picture of rebel leader Zhang Xianzhong

As if the realm hadn’t undergone enough suffering, 1633 marked the beginning of 2 new troubles in Ming China. In addition to the aforementioned constriction of the silver supply by the Japanese, a plague swept through northern China starting that year, originating in the devastated Shanxi province. The disease, nicknamed the “pimple plague” or the “vomit blood plague”, was probably a form of bubonic plague. Emperor Zhenchun reopened Macau to the outside world as a free port in order to alleviate the former issue as it began to nearly empty out the imperial treasury, also breaking the Japanese monopoly on trade between Europe and the Ming. However, he would not live to see the end of the latter for when the plague spread throughout Beijing in 1641, the Emperor was among its victims.

At first glance, the reign of Emperor Zhenchun could be considered a failure for the widespread destruction and chaos witnessed in the realm during his time. However, it was his capacity as a competent, well-regarded sovereign that ultimately allowed China to survive the 1620s and 1630s. Unlike his father, he had a good relationship with the scholarly bureaucrats and the army which prevented intrigue from getting in the way for the most part. In particular, Donglin scholar Qian Qianyi [5] rose to become the Grand Secretary and did much to prevent the administration from collapsing under all the external pressure and financial troubles without resorting to draconian measures. Under his reign, the northern frontier was relatively stable through the neutralization of Nurhaci’s Jurchens early on and the support for the Northern Yuan as a way to counterbalance the Jurchens. Although parts of the countryside were economically devastated and destabilized and would not recover for a few decades, the 1620s and 1630s saw an uptick in trade relations and mercantile activity in the coastal regions thanks to decreased taxes on merchants. Despite the rapid expansion of Japanese power abroad, the authority of the Ming emperor remained strong and legitimate enough for it to warrant respect, tribute, and even concessions from the “Oda kings” [6], as many in China referred to the hereditary Oda chancellors. All things considered, Emperor Zhenchun did the best he could with the bad hand he was given.

Portrait of Grand Secretary Qian Qianyi

After the death of his father, Prince Zhu Yousong succeeded his father and ascended to the throne as Emperor Hongguang [7]. Fortunately for the new sovereign, his reign would be significantly calmer than the Zhenchun Emperor’s was and Ming China would have an opportunity to recover from the chaos of the 1620s and 1630s.

[1]: OTL’s Tianqi Emperor

[2]: IOTL, due to the poor governance of the Taichang and Tianqi Emperors, the Donglin movement clashed head on with the pre-eminent eunuch faction and were purged in 1624. Although rehabilitated in 1627, they never fully recovered. ITTL, the movement has lasting influence not seen in OTL.

[3]: IOTL, the rebellion lasts until 1629 due to Ming resources much more strained IOTL.

[4]: IOTL, the rebellions continued on and combined with the Qing invasion, led directly to the fall of the Ming in 1644.

[5]: IOTL, due to court intrigue, is imprisoned by the Chongzhen Emperor in the early 1630s. Upon release, he is demoted in status to that of a commoner and never enters public service again.

[6]: Based on the fact that Ashikaga Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (足利義満) is given the title “King of Japan” by the Ming court.

[7]: The Hongguang Emperor is around IOTL, just as head of the nascent Southern Ming.

Last edited:

um, long live Emperor Hongguang?

The success of the Donglin movement and the opening of Macau did take China some steps closer to modernisation though, and the Hongguang Emperor may just as well cement it. The question is whether the full blossoming of Donglin's school of self-introspection and ethics — alongside the importation of relevant foreign knowledge and methods — will be fast enough to counteract the establishment of new conservative and "self-interest" factions that can ruin everything again, of which I doubt it is.

The success of the Donglin movement and the opening of Macau did take China some steps closer to modernisation though, and the Hongguang Emperor may just as well cement it. The question is whether the full blossoming of Donglin's school of self-introspection and ethics — alongside the importation of relevant foreign knowledge and methods — will be fast enough to counteract the establishment of new conservative and "self-interest" factions that can ruin everything again, of which I doubt it is.

Long live Emperor Hongguang!!um, long live Emperor Hongguang?

The success of the Donglin movement and the opening of Macau did take China some steps closer to modernisation though, and the Hongguang Emperor may just as well cement it. The question is whether the full blossoming of Donglin's school of self-introspection and ethics — alongside the importation of relevant foreign knowledge and methods — will be fast enough to counteract the establishment of new conservative and "self-interest" factions that can ruin everything again, of which I doubt it is.

The thing with the Donglin movement is that apparently it was opposed to Buddhism and Daoism whom many interpret as more liberal ideologies compared to Confucianism so it’s possible it eventually supplants other schools of thoughts and becomes the most conservative one through the flow of global events.

It seemed to allow for dissent and discourse however, if within the framework of Confucianism. Those can prove to be enough in stabilising the debates of the factions within the imperial court and bureaucracy, and even blossom into something that engenders — or at least permits — intellectual enlightenment and political r/evolution, likewise paving the way for the modernisation of the Chinese government and civil service.Long live Emperor Hongguang!!

The thing with the Donglin movement is that apparently it was opposed to Buddhism and Daoism whom many interpret as more liberal ideologies compared to Confucianism so it’s possible it eventually supplants other schools of thoughts and becomes the most conservative one through the flow of global events.

If anything, it can flip over and outdo Buddhism and Daoism in intellectual exercise and rigour, if only due to its relatively egalitarian origins from opposition of powerful court bureaucrats and unjust exercises of imperial power.

Moreover, the late emperor just survived things that could easily have been pretexts for a dynasty's loss of the mandate of heaven. That's one thing already going for them, and can prove to be as instrumental as the Lisbon Earthquake and the Thirty Years' War are to European strains of thought — secular and Christian.

That said, bureaucratic self-interests can still easily outdo those lofty ideals and possibilities, so it's one thing going against them. Or, at least it's a race between the things that make for the traditional dynastic cycle, and the more-advanced methodology arms race that's not too different from the French Ancien Regime that which can be stamped out for good by the former.

Last edited:

Chapter 64: Furuwatari War Part VII -The Flames of Defiance Extinguished

Chapter 64: Furuwatari War Part VII -The Flames of Defiance Extinguished

As the seasons changed from summer to fall in 1638, Azuchi was closing in on the Hojo. On the western front, Tokugawa Tadayasu was mobilizing an army in Sunpu set to march directly towards Odawara Castle while Kawajiri Shigenori was making similar preparations in Kai province after both fighting Takeda Nobumichi directly and contributing to Nobutomo’s armies. To the north, northern Musashi had been conquered by Oda-Azuchi forces, and to the east the Hojo had been completely ousted out of Shimousa province. Furthermore, just before the Battle of Fukaya, Satomi Toshiteru switched sides and would help defeat the Hojo in Kazusa province. Back in Hachioji Castle, Ujinobu hatched a final plan to somehow topple the Oda-Azuchi regime. Leaving 10,000 in and around Hachioji Castle with Hojo Ujinaga, he left for Odawara Castle with the rest of his remaining army in the hopes of punching through the Kawajiri and Tokugawa armies eyeing the Hojo home castle before marching along the Tokaido straight towards Gifu. The goal was to cause enough chaos to gather ex-rebels in Mikawa province, cut off Nobutomo from Azuchi, and force him to leave the Kanto region. By the time he arrived in the vicinity of Odawara Castle in September 1638, Ujinobu had an army of 22,000. However, many of his men were exhausted from the unrelenting marches. Nevertheless, the Hojo army remained committed to their lord and Ujinobu continued on, entering Suruga province and encamping in Gotemba (御殿場). There, he would rest and awaited intelligence on the movements of the nearby Tokugawa and Kawajiri armies. However, the seemingly inevitable battle would never come even as Tadayasu and Shigenori prepared to assault the Hojo army from the north and west with a total of 17,000 men. News came to Ujinobu of the collapse of Hojo presence in Musashi province as Nobutomo’s armies overwhelmed the rest of the province, including the army of 10,000 left to hold out near Hachioji Castle. Additionally, Ujinobu’s final gamble was viewed by many of his men in Musashi as the abandonment of the province, causing many to desert or defect and shaking the loyalties of the remainder of the Hojo military. The Hojo lord, disheartened by the situation in Musashi and realizing his end as inevitable, would commit seppuku in shame after reaching out to the Tokugawa, asking that his men be spared. His final wish was granted, although some of his men would choose instead to split off and continue to fight rather than surrender. These would be the exceptions, for Odawara would also unconditionally surrender and the rest of the Hojo would soon follow.

After the Hojo surrender, only the Ashina, Nihonmatsu, and Kasai clans in Mutsu province remained in arms against Azuchi. After the Battle of Esashi, Sakuma Noritora and Nanbu Shigenao received even more reinforcements from other clans as Kasai Kiyonobu retreated completely. Possessing too few men, the Kasai clan was limited to defending its remaining castles. By the end of October, the main castle of Teraike Castle (寺池城) had fallen as well, and Kiyonobu, who by now was on the run, was captured a few weeks later. With the final fall of the Kasai, the last hurrah of the war would take place in the lands of the Ashina clan. The latter had retreated together with the surviving elements of the Nihonmatsu clan, whose castle had fallen to the Date earlier, back to Aizu. By then, rumors of invasions by other clans had been confirmed, with a 15,000 strong army of the Echigo lords led by Irobe Mitsunaga having crossed into Ashina territory and Utsunomiya Yoshitsuna mobilizing an army himself in Shimotsuke province. Although Mitsunaga’s army theoretically outnumbered the Ashina-Nihonmatsu field army, the former faced local resistance and could not move decisively towards Kurokawa Castle (黒川城) [1], allowing Ashina Morinori to strengthen his numbers and eastern defenses. Finally, at the beginning of September, Nihonmatsu Yoshitada left the castle at the head of the 11,000-strong main army, and faced off against Mitsunaga a week later at Aizubange (会津坂下). Yoshitada placed his own retinue numbering 2,500 at the front end of the army jutting out somewhat, with the Ashina men in the reserves and wings, while the Echigo army was more uniform in its formation. The Nihonmatsu lord would lead his personal vanguard, significantly raising the morale of his men. The battle commenced at the crack of light, the Nihonmatsu contingent sprinting ahead of the rest of the army and crashing straight into the unsuspecting enemy. Although this charge came close to breaking through and overrunning Mitsunaga’s personal position, the rest of Yoshitada’s army had not caught up with his vanguard and parts of the Echigo army’s wings surrounded the front contingent. Before the wings could wholly arrive and aid the Nihonmatsu vanguard, Yoshitada was killed while rallying his men to form a more defensive formation. News of his death quickly spread throughout the Ashina-Nihonmatsu ranks and the Ashina majority of the army quickly retreated, leaving the vanguard to fight to the last man over their lord’s body. The Nihonmatsu clan had ceased to exist.

After the Hojo surrender, only the Ashina, Nihonmatsu, and Kasai clans in Mutsu province remained in arms against Azuchi. After the Battle of Esashi, Sakuma Noritora and Nanbu Shigenao received even more reinforcements from other clans as Kasai Kiyonobu retreated completely. Possessing too few men, the Kasai clan was limited to defending its remaining castles. By the end of October, the main castle of Teraike Castle (寺池城) had fallen as well, and Kiyonobu, who by now was on the run, was captured a few weeks later. With the final fall of the Kasai, the last hurrah of the war would take place in the lands of the Ashina clan. The latter had retreated together with the surviving elements of the Nihonmatsu clan, whose castle had fallen to the Date earlier, back to Aizu. By then, rumors of invasions by other clans had been confirmed, with a 15,000 strong army of the Echigo lords led by Irobe Mitsunaga having crossed into Ashina territory and Utsunomiya Yoshitsuna mobilizing an army himself in Shimotsuke province. Although Mitsunaga’s army theoretically outnumbered the Ashina-Nihonmatsu field army, the former faced local resistance and could not move decisively towards Kurokawa Castle (黒川城) [1], allowing Ashina Morinori to strengthen his numbers and eastern defenses. Finally, at the beginning of September, Nihonmatsu Yoshitada left the castle at the head of the 11,000-strong main army, and faced off against Mitsunaga a week later at Aizubange (会津坂下). Yoshitada placed his own retinue numbering 2,500 at the front end of the army jutting out somewhat, with the Ashina men in the reserves and wings, while the Echigo army was more uniform in its formation. The Nihonmatsu lord would lead his personal vanguard, significantly raising the morale of his men. The battle commenced at the crack of light, the Nihonmatsu contingent sprinting ahead of the rest of the army and crashing straight into the unsuspecting enemy. Although this charge came close to breaking through and overrunning Mitsunaga’s personal position, the rest of Yoshitada’s army had not caught up with his vanguard and parts of the Echigo army’s wings surrounded the front contingent. Before the wings could wholly arrive and aid the Nihonmatsu vanguard, Yoshitada was killed while rallying his men to form a more defensive formation. News of his death quickly spread throughout the Ashina-Nihonmatsu ranks and the Ashina majority of the army quickly retreated, leaving the vanguard to fight to the last man over their lord’s body. The Nihonmatsu clan had ceased to exist.

Battle of Aizubange (Salmon=Echigo, Brown=Nihonmatsu, Blue=Ashina)

The remnants of the army retreated back to Kurokawa Castle where they entrenched themselves on the western side of the castle in anticipation of the Echigo army’s advance. They engaged with Mitsunaga in various engagements throughout the fall, with the Ashina’s number slowly being whittled down. Eventually, the armies of Utsunomiya Yoshitsuna and Date Norimune arrived in the vicinity of the castle and surrounded it. Nevertheless, the Ashina men held on through the relentless attacks by 3 different armies until December, until the cold finally compromised their provisions and exposed their battered position. Morinori, offering his head in return for his remaining men to be spared, finally surrendered. Although scattered forces throughout the Oshu, Kanto, and Chubu regions would intermittently resist into the early spring of 1639, the war was officially over.

The Furuwatari War, although a victory for the Oda Chancellorate, took a heavy toll on the realm. Large tracts of the east, particularly Musashi, Mikawa, and Mutsu provinces, were left devastated and depopulated and would not fully recover for a few decades. Some of this was attributable to the unprecedented usage of gunpowder weapons, particularly cannons, Im battles, skirmishes, and sieges. The downfall of so many clans and lords also chaotically ended existing social orders and hierarchies. The biggest example of this was the Hojo clan, who as one of the biggest landholders in Japan were nearly wiped out in the conflict. Notably, the Furuwatari War was the last large scale feudal war to take place in Japan, where often old rivalries between different clans superseded the greater objectives of the war in influencing loyalties and conduct.

The victory of Nobutomo and the Oda government in Azuchi, however, would decisively move Japan towards greater centralization. This trend would begin with Nobutomo’s postwar actions in regards to the affected areas. Although as before, land belonging to rebel clans would be redistributed to feudal lords who had remained loyal to Azuchi as well as Nobutomo’s own relatives, the Kamakura-fu was abolished. Henceforth, the Kanto region would be directly governed from Azuchi like the rest of the home islands. Oda Toshinao, however, would be compensated by being given the entirety of Musashi province, which while devastated was geographically still key in controlling the entire Kanto region, although his landholdings would be redistributed to native Kanto lords who had fought for Azuchi in the war. Nobutomo stayed in Kamakura until February 1639 to oversee the aftermath of the war and assigned Takigawa Kazutoshi and Toshinao's uncle Tamemasa (織田為昌) to finish the work, for he received word of the arrival in Sakai of someone he had eagerly waited for.

His youngest brother, Oda Tomoaki, had come home from Europe together with the rest of the embassy that had left 4 years earlier, and the chief representative had much to share with Nobutomo, from stories to gifts.

The Furuwatari War, although a victory for the Oda Chancellorate, took a heavy toll on the realm. Large tracts of the east, particularly Musashi, Mikawa, and Mutsu provinces, were left devastated and depopulated and would not fully recover for a few decades. Some of this was attributable to the unprecedented usage of gunpowder weapons, particularly cannons, Im battles, skirmishes, and sieges. The downfall of so many clans and lords also chaotically ended existing social orders and hierarchies. The biggest example of this was the Hojo clan, who as one of the biggest landholders in Japan were nearly wiped out in the conflict. Notably, the Furuwatari War was the last large scale feudal war to take place in Japan, where often old rivalries between different clans superseded the greater objectives of the war in influencing loyalties and conduct.

The victory of Nobutomo and the Oda government in Azuchi, however, would decisively move Japan towards greater centralization. This trend would begin with Nobutomo’s postwar actions in regards to the affected areas. Although as before, land belonging to rebel clans would be redistributed to feudal lords who had remained loyal to Azuchi as well as Nobutomo’s own relatives, the Kamakura-fu was abolished. Henceforth, the Kanto region would be directly governed from Azuchi like the rest of the home islands. Oda Toshinao, however, would be compensated by being given the entirety of Musashi province, which while devastated was geographically still key in controlling the entire Kanto region, although his landholdings would be redistributed to native Kanto lords who had fought for Azuchi in the war. Nobutomo stayed in Kamakura until February 1639 to oversee the aftermath of the war and assigned Takigawa Kazutoshi and Toshinao's uncle Tamemasa (織田為昌) to finish the work, for he received word of the arrival in Sakai of someone he had eagerly waited for.

His youngest brother, Oda Tomoaki, had come home from Europe together with the rest of the embassy that had left 4 years earlier, and the chief representative had much to share with Nobutomo, from stories to gifts.

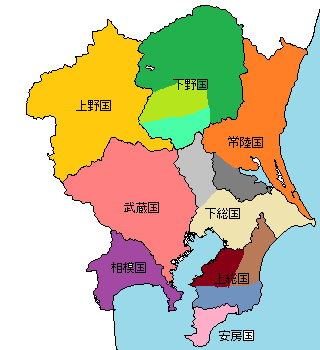

Redistribution of lands:

Kanto region

Salmon= Oda Toshinao (織田利直) 1618-

Orange= Satake Yoshitaka (佐竹義隆) 1609-

Light orange= Takigawa Kazutoshi (滝川一利) 1583-

Forest green= Utsunomiya Yoshitsuna (宇都宮義綱) 1598-

Lime green= Sano Hisatsuna (佐野久綱) 1600-

Emerald green= Oyama Toshiyasu (小山利泰) 1595-

Dark grey= Minagawa Takatsune (皆川隆庸) 1581-

Light grey=Hasegawa Hidemasa (長谷川秀昌) 1600-

Purple= Murai Sadamasa (村井貞昌) 1586- [2]

Cobalt= Uesugi Noritoshi (上杉憲俊) 1579-

Brown=Ikoma Takatoshi (生駒高俊) 1611-

Maroon=Date Norimune (伊達則宗) [3] 1600-

Pink= Satomi Toshiteru (里見利輝) 1614-

Beige=minor castle lords

(Izu Province not shown) [4]

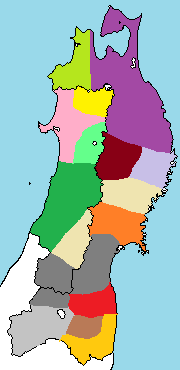

Oshu region

Purple= Nanbu Shigenao (南部重直) 1606-

Light purple= Kyogoku Takahiro (京極高広) 1599-

Maroon= Endou Yoshitoshi (遠藤慶利) 1609-

Yellow= Mōri Tadakatsu (毛利忠勝) 1594-

Orange= Tooyama Noritomo (遠山則友) 1609-

Light orange= Satake Yoshitaka (佐竹義隆) 1609-

Light grey= Mogami Yoshitoshi (最上義智) 1631-

Dark grey= Date Tadamune (伊達忠宗) 1591-

Red= Souma Tomotane (相馬朝胤) 1619-

Green= Sakuma Moritora (佐久間盛虎) 1619-

Lime green= Tsugaru Nobuhide (津軽信英) 1620-

Emerald green= Tozawa Masamori (戸沢政盛) 1585-

Pink= Akita Sanesue (秋田実季) 1576-

Brown= Shirakawa Yoshitsuna (白川義綱) 1592-

Beige=Minor castle lords

Kanto region

Salmon= Oda Toshinao (織田利直) 1618-

Orange= Satake Yoshitaka (佐竹義隆) 1609-

Light orange= Takigawa Kazutoshi (滝川一利) 1583-

Forest green= Utsunomiya Yoshitsuna (宇都宮義綱) 1598-

Lime green= Sano Hisatsuna (佐野久綱) 1600-

Emerald green= Oyama Toshiyasu (小山利泰) 1595-

Dark grey= Minagawa Takatsune (皆川隆庸) 1581-

Light grey=Hasegawa Hidemasa (長谷川秀昌) 1600-

Purple= Murai Sadamasa (村井貞昌) 1586- [2]

Cobalt= Uesugi Noritoshi (上杉憲俊) 1579-

Brown=Ikoma Takatoshi (生駒高俊) 1611-

Maroon=Date Norimune (伊達則宗) [3] 1600-

Pink= Satomi Toshiteru (里見利輝) 1614-

Beige=minor castle lords

(Izu Province not shown) [4]

Oshu region

Purple= Nanbu Shigenao (南部重直) 1606-

Light purple= Kyogoku Takahiro (京極高広) 1599-

Maroon= Endou Yoshitoshi (遠藤慶利) 1609-

Yellow= Mōri Tadakatsu (毛利忠勝) 1594-

Orange= Tooyama Noritomo (遠山則友) 1609-

Light orange= Satake Yoshitaka (佐竹義隆) 1609-

Light grey= Mogami Yoshitoshi (最上義智) 1631-

Dark grey= Date Tadamune (伊達忠宗) 1591-

Red= Souma Tomotane (相馬朝胤) 1619-

Green= Sakuma Moritora (佐久間盛虎) 1619-

Lime green= Tsugaru Nobuhide (津軽信英) 1620-

Emerald green= Tozawa Masamori (戸沢政盛) 1585-

Pink= Akita Sanesue (秋田実季) 1576-

Brown= Shirakawa Yoshitsuna (白川義綱) 1592-

Beige=Minor castle lords

[1]: Old name of Aizu Castle (会津城) which doesn’t change in 1592 ITTL like it did IOTL.

[2]: Murai Sadamasa was relocated and given more land from the province of Izumi.

[3]: ITTL’s Date Hidemune [5]

[4]: Oota Nobufusa (太田信房) allotted Izu province, preserving the Hojo bloodline.

[5]: Yes, the Date Tadamunes of OTL and TTL are brothers but due to naming conventions have different names.

Last edited:

Well, there goes the Hojo Clan. It was a good run, from Hojo Soun, but they ended up playing their cards wrong. Also, if I remember, what's left of the Takeda Clan was eliminated as well.

Yup. In terms of the tozama daimyo, it’s really just the Mōri left that can levy tens of thousands of men against Azuchi hypothetically but at this point Japan’s trade expansionist policies benefit them too much for them to go against the Oda.Well, there goes the Hojo Clan. It was a good run, from Hojo Soun, but they ended up playing their cards wrong. Also, if I remember, what's left of the Takeda Clan was eliminated as well.

They did gain some lands and also Norimune’s brother was given his own fief in the Kanto region so there’s that.Guess the Date aren't getting the north this time. Oh well.

Last edited:

Chapter 65: The Oda Meet The Bourbons

Chapter 65: The Oda Meet The Bourbons

News of Japan’s victory over the Spanish Empire, particularly of its naval victories, in the Iberian-Japanese War spread like wildfire and festered especially throughout its royal courts. Curiosity and praise towards the rising Eastern power quickly arose among the anti-Habsburg nations in particular, with countries like Sweden and Denmark beginning to even take an interest in trade relations with Asia. To many Protestants, the Japanese victory demonstrated Catholic weakness and shined hope upon their fortunes against the Habsburgs in the Imperial Liberties’ War, the latter which was eventually won by the Protestant side in 1635. The Dutch also basked in praise for their own successes in the war, although given the facts of the war they perhaps were over-credited. No country, however, took a greater interest in the outcome of the war in Europe than France. Although a Catholic nation, the French had a history of collaborating with non-Catholic nations against the Habsburgs from the reign of Francis I in the early 16th century onwards, from the Ottoman Empire to the Netherlands. Additionally, the Bourbon monarchy practiced religious tolerance towards its Huguenot subjects and were thus not as politically Catholic as inquisitorial Spain or Austria. That being said, the French would be entering new territory for unlike the Iberians, Dutch, or the English, the former possessed no maritime reach into Asia. This fact did not deter Cardinal Richelieu, France’s chief minister, from taking the first step towards establishing diplomatic relations with Japan, including an invitation to Paris by any representatives potentially sent by Azuchi. He worked with the Dutch, his wartime ally, to arrange a voyage to Japan due to the latter’s close relations with the Japanese and maritime power in Asia.

In March 1635, the Franco-Dutch delegation, led by bureaucrat Philippe Segura, arrived in Sakai and within days were permitted audience to the daijo-daijin, who was eager to meet the Frenchmen in particular and learn more about France, a country he had only heard of. With the aid of translators, the French representative delivered the warm words of King Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu inviting the forging of official relations between the two realms to Nobutomo and presented him with a rapier and other various gifts. Accustomed to entertaining merchants and colonial officials, Nobutomo was intrigued at the fact that now European royalty had directly sent someone to Azuchi all the way from the home country. Seeing an opportunity, he resolved not just to send a delegation to Europe and learn more about a continent Japan already had many connections to but to dispatch a group representing the best of the realm in the hopes of captivating the awe of Europe. He would select his youngest brother Tomoaki to lead the embassy, with the young noble Nakanoin Michizumi (中院通純) and Ikeda Nobutora (池田信虎) [1] acting as deputies and the Sakai merchant Kurata Yasubee (倉田保兵衛) [2] also accompanying them. Although there were concerns of interacting with yet another Catholic nation among some in the government, French religious tolerance and lack of any presence in Asia that could threaten Japan would assuage these fears.

Oda Tomoaki was the perfect person to lead the embassy, for among Nobutomo’s brothers, Tomoaki was the closest to the chancellor. While Tomoaki’s older brothers Konoe Tomoshige and Kanbe Tomoyoshi became young heirs of different families and had already left Gifu even before Nobutomo ousted Saito Yoshioki in 1619, Tomoaki had had stayed by his brother’s side in Gifu until Nobutomo’s ascension to the chancellorship in 1630. He had gone on to assist his older brother in administrative matters, even briefly joining Kanbe Tomoyoshi’s army in Bireitō during the Iberian-Japanese War before returning to Azuchi after falling ill. Like Nobutomo, Tomoaki was fluent in Chinese and had experience speaking and dealing with foreign merchants, even picking up some Spanish in the process.

In March 1635, the Franco-Dutch delegation, led by bureaucrat Philippe Segura, arrived in Sakai and within days were permitted audience to the daijo-daijin, who was eager to meet the Frenchmen in particular and learn more about France, a country he had only heard of. With the aid of translators, the French representative delivered the warm words of King Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu inviting the forging of official relations between the two realms to Nobutomo and presented him with a rapier and other various gifts. Accustomed to entertaining merchants and colonial officials, Nobutomo was intrigued at the fact that now European royalty had directly sent someone to Azuchi all the way from the home country. Seeing an opportunity, he resolved not just to send a delegation to Europe and learn more about a continent Japan already had many connections to but to dispatch a group representing the best of the realm in the hopes of captivating the awe of Europe. He would select his youngest brother Tomoaki to lead the embassy, with the young noble Nakanoin Michizumi (中院通純) and Ikeda Nobutora (池田信虎) [1] acting as deputies and the Sakai merchant Kurata Yasubee (倉田保兵衛) [2] also accompanying them. Although there were concerns of interacting with yet another Catholic nation among some in the government, French religious tolerance and lack of any presence in Asia that could threaten Japan would assuage these fears.

Oda Tomoaki was the perfect person to lead the embassy, for among Nobutomo’s brothers, Tomoaki was the closest to the chancellor. While Tomoaki’s older brothers Konoe Tomoshige and Kanbe Tomoyoshi became young heirs of different families and had already left Gifu even before Nobutomo ousted Saito Yoshioki in 1619, Tomoaki had had stayed by his brother’s side in Gifu until Nobutomo’s ascension to the chancellorship in 1630. He had gone on to assist his older brother in administrative matters, even briefly joining Kanbe Tomoyoshi’s army in Bireitō during the Iberian-Japanese War before returning to Azuchi after falling ill. Like Nobutomo, Tomoaki was fluent in Chinese and had experience speaking and dealing with foreign merchants, even picking up some Spanish in the process.

Portrait of Oda Tomoaki

While the small Franco-Dutch delegation would remain a bit longer in Japan, the Kanei Embassy (寛永の使節), as Azuchi’s first ever diplomatic mission would be referred to, strove ahead and departed Sakai in June 1635, consisting of 2 galleons and carrying a few hundred men. The voyage would be a long and arduous one, with multiple stops along the way that exposed the group to the wider world between Europe and Japan. Aside from an overnight stay in Aparri, these stops would include Malacca and Pulicat, all of whom were Dutch possessions. Although a few daring Japanese merchants had visited Indian ports, the entourage were nevertheless still breaking into new ground and received firsthand exposure to Hinduism, which Michizumi noted as having certain similarities to their own faiths. After Pulicat would come a much longer stretch of time until the embassy landed in Bordeaux in March 1636. The French, who had been expecting them, greeted them cordially and gave them special quarters for them to rest in. After spending a few days recuperating in the French port, the embassy began a days-long march through the countryside towards Paris, where a curious and excited crowd awaited the guests.

The entourage entered the French capital in splendor, with Tomoaki leading at the front on horseback. Donning a bright blue hitatare (直垂) and flanked by elite Oda guards armed with arquebuses and spears, he captured the imagination and excitement of the Parisian people, and the rest of the embassy was no less impressive. Descriptions of the Japanese entry quickly spread and captivated the minds of many in Europe, including the Spanish and Portuguese who despaired at the opportunity they could’ve had had the war not occurred. Tomoaki, however, wasn’t done impressing the French. At his and his entourage’s greeting of King Louis XIII before a host of aristocrats and ministers, including Cardinal Richelieu, he spoke a few sentences in French that he had practiced beforehand to the king before continuing on in Spanish with the assistance of a Dutch translator, declaring Azuchi’s interest in establishing a mutual agreement of friendship between the two realms. The various gifts to the king were also presented, from the feathers of the red-crowned crane to silver from the Iwami silver mines. In response to the gift of the rapier to Nobutomo back in Azuchi, Tomoaki also personally presented a katana to Louis XIII. The king thanked him and eagerly accepted the promise of diplomatic friendship before assigning the hospitality of the entourage to the household of Henri, the Prince of Conde.

Oda Tomoaki’s hitatare

The impression the Japanese, particularly Tomoaki, left on Paris would not be forgotten. Richelieu especially was fascinated with the Japanese “samurai prince”, as he came to be known, and was interested in conversing with him. After the fateful day, Tomoaki would be invited to Richelieu’s palace every so often, where they spoke about the politics and culture of the two countries. Tomoaki learned much about France from Richelieu, who throughout his tenure as Louis XIII’s chief minister had consolidated royal power and weakened the influence of the nobility, centralizing the French state, and took note of the cardinal’s political reforms and accomplishments. The “samurai prince” also received many invitations from various nobles and to their parties, often receiving the flirtations of the daughters. Though he never had any affairs in Paris and remained loyal to his wife back home, Tomoaki nevertheless was very popular among the Parisian women. He however, became good friends and even an indirect mentor to the Prince of Conde’s son, Louis. 13 years his junior, Louis was a student at the Royal Academy in Paris when Tomoaki entered the city and almost immediately idolized the guest of his household. The Conde heir was fascinated with the traditions of the samurai especially when it came to the traditions of samurai cavalry and during Tomoaki’s stay would ask him about them in his free time. On numerous occasions, the two even rode together around the countryside surrounding Paris on their steeds. Tomoaki’s time with him would leave a long-lasting impression on the young Bourbon prince, who would go on to be one of France’s finest generals, and the future Prince of Conde would even incorporate some samurai cavalry traditions into his combat style and tactics as a commander.

Portrait of Louis, duke of Enghiens and the future Prince of Conde, in his youth

The Oda brother would also get a firsthand opportunity to witness the tactics and technology of European warfare when he traveled to the Low Countries in 1637 to witness the Battle of Arras. By then, the Franco-Dutch alliance had begun to gain the upper hand against the Spanish Empire after Portugal had risen up against the Habsburg monarchy and declared independence. The Portuguese regiments in the Army of Flanders had mutinied upon the raising of Braganza’s banner in Lisbon, forcing the Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand to divert Spanish troops towards defeating the rebel regiments. Although largely successful, a few thousand Portuguese soldiers managed to slip away and join the French against their former overlords. These events enabled Frederick Henry, the Prince of Orange, to reinvigorate the spirits of his countrymen and convince the Dutch States’ General to increase war expenditures for a new offensive again into the Spanish Netherlands. It was in this situation did Oda Tomoaki witness the French army contend with the might of the Spanish tercios and triumph over, resulting in the eventual conquest of the whole of Artois. Although he wanted to participate himself directly, his retainers strongly advised not to so as to avoid a diplomatic breach in the Treaty of Gapan and the risk of renewed war between Spain and Japan.

Depiction of the 1637 Battle of Arras

In addition to their activities in France, Tomoaki and the others also visited London, Copenhagen, Stockholm, and the Hague throughout 1637 to greet King Charles I of England and Scotland, the Dutch States General, King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, and King Christian IV of Denmark. These trips would be fruitful in furthering commercial and diplomatic relations with England and the Netherlands, especially the English whose presence in Southeast Asia was disparate and tenuous. That being said, Tomoaki in his writings would admit his distaste for the English monarch because of his self-righteous pride and refusal to work with his subjects through Parliament. Meanwhile, the visits to Stockholm and Copenhagen would do much to spark the 2 countries’ mercantile and colonial ventures in Asia, with the former already eyeing opportunities in North America, although no agreements were signed with Sweden or Denmark by the Japanese. The embassy, however, was witness to a Swedish military exercise by Gustavus Adolphus’ professional standing army, and the Japanese were blown away by the discipline and effectiveness of the Swedes and their line infantry.

The embassy’s stay would be cut short when in mid-1638, they received news of the beginning of the Furuwatari War. Tomoaki, wanting to be by his brother’s side at that critical moment, immediately made preparations to depart for his homeland along with Michizumi. Yasubee and Nobutora would stay for another year and complete unfinished business, including a trip to Brandenburg-Prussia before leaving Europe in 1639. Bidding farewell to the king and the many friends he had made during his stay in Paris, he set sail in late July 1638, arriving back in Sakai in late February 1639. By the time the Oda representative was home, the war was over with a victory for Azuchi, albeit costing the life of his older brother Konoe Tomoshige. Despite his absence, Tomoaki was welcomed home and celebrated for his brave journey to Europe and dignified conduct and commitment to duty while so far off. What he had brought home, however, was incalculably more significant. From the embassy’s cargo came gifts and other items, from wine and a set of a doublet and breeches specifically for the daijo-daijin to several flintlock muskets only recently invented in France as well as an ornate Malay kris dagger for the emperor. The ships also carried detailed records and writings of the journey itself as well as everything seen and experienced in Europe. From Tomoaki and Michizumi came stories and vivid descriptions of what they had seen and experienced. The return of Nobutora and Yasubee the following year would bring even more tales and goods to Azuchi.

Though cut short, the Kanei Embassy proved to be one of significant consequence. It provided Europe with its first direct impression of Japan and what they saw captivated their interest, establishing Japan’s reputation as a heathen power that nevertheless commanded their respect and could even be trusted at times, unlike the Ottomans. The embassy would especially spark friendly and altruistic relations between France and Japan and incentivize the former to invest more in its mercantile interests in the East from the impetus of the Franco-Japanese mutual agreements over trade and friendship drafted and signed by both parties during the embassy’s stay. As for Japan, the embassy gave them a much wider view of the world and a wealth of knowledge on the customs, traditions, and technologies of Europe, and its success would lead to future embassies. In particular, the politics of the visited countries interested Nobutomo, who would derive inspiration from them in his planned reforms for the realm. Finally, the Kanei Embassy provided one particular empire in Eastern Europe a glimpse of who they would be encountering once they inevitably reached the Pacific coast.

[1]: Son of the former foreign affairs magistrate, Ikeda Masatora.

[2]: No connection to OTL.

Last edited:

I wonder if there's also inspiration the other way around, where the Japanese sengoku daimyo system will give the French ideas in formulating schemes to better exercise their control over the First and Second Estates while improving its administration. While the centralised Royal government and treasury will always be there to stay, who knows that they won't be more... roundabout, in dealing with the nobility and their landholdings.Richelieu especially was fascinated with the Japanese “samurai prince”, as he came to be known, and was interested in conversing with him. After the fateful day, Tomoaki would be invited to Richelieu’s palace every so often, where they spoke about the politics and culture of the two countries. Tomoaki learned much about France from Richelieu, who throughout his tenure as Louis XIII’s chief minister had consolidated royal power and weakened the influence of the nobility, centralizing the French state, and took note of the cardinal’s political reforms and accomplishments.

The Palace of Versailles may even be somewhat inspired by the Japanese alternate attendance system ITTL.

Welp; those tactics can prove to be a rather unpleasant surprise to their foes, like the more persistent energy that a circular formation can give.Tomoaki’s time with him would leave a long-lasting impression on the young Bourbon prince, who would go on to be one of France’s finest generals, and the future Prince of Conde would even incorporate some samurai cavalry traditions into his combat style and tactics as a commander.

There goes the unquestioning acclaim for the Sonno Joi movement.That being said, Tomoaki in his writings would admit his distaste of the English monarch because of his self-righteous pride and refusal to work with his subjects through Parliament.

Last edited:

Very nice chapter. Wonder if anymore Japanese embassies will be established with places like the Ottoman Empire or Sweden

Lovely chapter, hopefully the French learn from the japanese on how to effectively break the back of the aristocracy and rule the realm trough a mixture of power, same with the Prince of Conde who instead of just countering the Spanish can hopefully occupy the whole of the Spanish Netherlands when the next opportunity comes.

Franco Japanese friendship is not often something you see so I'm interested in seeing it play out more.

Franco Japanese friendship is not often something you see so I'm interested in seeing it play out more.

Threadmarks

View all 150 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 131: Daijo-daijin Nobuie and a 17th Century Retrospective Map of Daimyo 1697 Chapter 132: Food, Fashion, and Popular Leisure in Late 17th Century Japan Chapter 133: Yongwu and his Neighbors Chapter 134: Rise of the Gekijo - Music and Theater In 17th Century Japan Chapter 135: Upheavals in English North America Chapter 136: Early Days of the Era of Nobuie Chapter 137: Dutch or French

Share: