You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Stars and Sickles - An Alternative Cold War

- Thread starter Hrvatskiwi

- Start date

-

- Tags

- cold war

Threadmarks

View all 122 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 98: The Conqueror? - Uganda (Until 1980) (Part 2) Chapter 99: Slaying the Beast - Uganda (Until 1980) (Part 3) Chapter 100 [SPECIAL] - Ad Astra - Aerospace Competition Between the Superpowers (Until 1980) (Part 1) Chapter 101 [SPECIAL] - Magnificent Desolation - Aerospace Competition Between the Superpowers (Until 1980) (Part 2) Chapter 102: Jadi Pandu Ibuku - Nusantara (Until 1980) Chapter 103: Furtive Seas - South Maluku and West Papua (Until 1980) Chapter 104: Kings and Kingmakers - Post-Independence North Kalimantan (Until 1980) Chapter 105: Maka-Diyos, Maka-Tao, Makakalikasan, at Makabansa - The Philippines (Until 1980)Continental Western Europe being dominated by a French junta? Sounds like a reversal of the OTL 68er outbreaks of political change, with the West losing its supposed moral high ground over the eastern bloc. Like the Greek junta from ‘67-‘74, only on a wider scale.

I’d hope to see that system start to fray apart with the passing of Franco, leaving Spain a weak link in the Nouvelle Droite.

The underlying ideology of the 68ers is still very present ITTL, but is being actively suppressed by a more aggressively reactionary state apparatus. The whole point of supporting the Nouvelle Droite was to try to provide legitimacy amongst the intelligentsia and displace the dominance of the New Left. I guess the big winner was Gramscianism, since both the New Left and the Nouvelle Droite draw heavily on Gramsci's Prison Notebooks.

And yes - I have a question.

The fact is that now I have another peak of fascination with old horror films, and I'm worried about what has become of the Hammer studio and the Italian Gothic.

Still - once in France dictatorship, does it mean that the "New Wave" is covered?

Culture has been a realm these regimes haven't really concerned themselves with, so hammer films, the Italian Gothic and the French New Wave still occur largely as OTL. Obviously these individual governments are gonna have issue with individual film-makers, but the culture is generally OTL.

So Jean-Luc Godard will become even more scandalous.Culture has been a realm these regimes haven't really concerned themselves with, so hammer films, the Italian Gothic and the French New Wave still occur largely as OTL. Obviously these individual governments are gonna have issue with individual film-makers, but the culture is generally OTL.

Chapter 72: A Great Civilisation - Iran (Until 1980)

For more information about Iran (1940s), see: https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...-an-alternative-cold-war.280530/#post-7699657

===

Shahanshah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last monarch of Iran

From the anti-Mossadegh coup of 1953, the Iranian regime was haunted by a crisis of legitimacy. Having overthrown a popular nationalist leader with support from the 'imperialists', the government of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi desperately needed a raison d'être for his autocratic control of the state. He would eventually find this purpose in the modernisation and Westernisation of his country. At first, however, he would be preoccupied with reestablishing monarchical control over the domestic political landscape in Iran. After the coup, the real power behind the throne lay with the Shah's Prime Minister, General Fazlollah Zahedi. At this stage, American and British diplomatic circles, as well as large parts of the Iranian elite, held the Shah in contempt, seeing him as a weak-willed figurehead. Mohammad Reza proved a surprisingly astute politician, and learn to consolidate his power by playing off various factions of the elite against each other. The Shah cultivated an image of a merciful ruler, imprisoning political opponents, such as the supporters of Mossadegh's National Front, and then pardoning them. Many had instead expected a bloody purge. Seeking to broaden his support base, Mohammad Reza ended up adopting many of the policies of the banned National Front, hoping that popular approval could counteract any planned sedition from elites that opposed his reform plans. In 1955, the Shah dismissed General Zahedi and appointed Hossein Ala', who governed as Prime Minister until 1957. In the mid-1950s, the Shah also intended to develop a non-Islamic identity in Iran. In order to do so, he emphasised Iran's Achaemenid imperial past, drawing parallels between himself and Cyrus the Great. He also promised to bring Iranian living standards to the level of the Western nations. To satiate the ulema, who were critical of his de-emphasising of the Islamic past of Iran, he resumed the traditional persecution of Baha'i faithful, razing the primary Baha'i temple in Tehran and passing a law banning Baha'i from publicly congregating.

Privately, the Shah's marriage with his second wife, Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiary, was becoming increasingly strained, as Queen Soraya clashed with Ernest Perron, a homosexual Swiss who was the Shah's personal secretary, confidante and best friend. Perron seemed to enjoy antagonising the Queen, offending her greatly when he arrived at her palace and proceeded to ask lewd questions about her and the Shah's sex life. The marriage between the two would end in 1958, when no remedy could be found to the Queen's infertility. Despite his constant philandering, those close to the Shah would attest that he always loved Soraya, even after their divorce, and she lived out the rest of her days as a wealthy socialite in Paris, her favourite city.

On 27th February 1958, Iranian commander Valiollah Gharani attempted a coup d'etat against the Shah. The coup failed, but it was soon discovered by SAVAK, the Iranian intelligence agency, that Gharani had met with American officials in Tunisia [174]. The Shah demanded that from thereon American officials were not authorised to contact the opposition. Insecure in US support for his regime, in January 1959 the Shah began negotiations for a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union. Receiving furious telegrams from President Eisenhower, in the end the Shah refused to sign an agreement. Soviet dissatisfaction with the Shah's refusal to pledge non-aggression against the Communist superpower led the KGB to attempt to assassinate Mohammad Reza on multiple occasions, nope of which were successful, largely due to the leaking of these plots by KGB station chief in Tehran, Vladimir Kuzichkin.

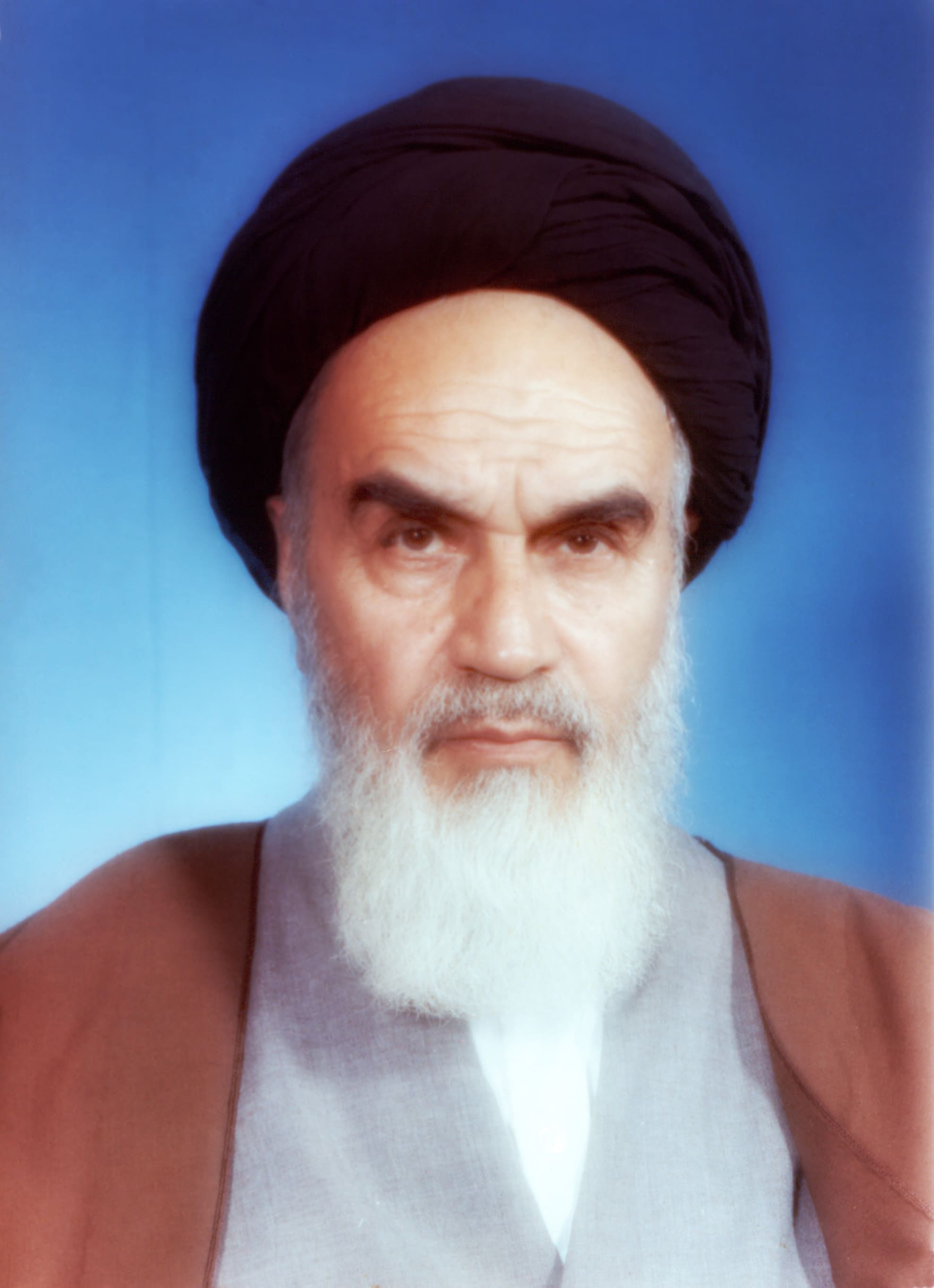

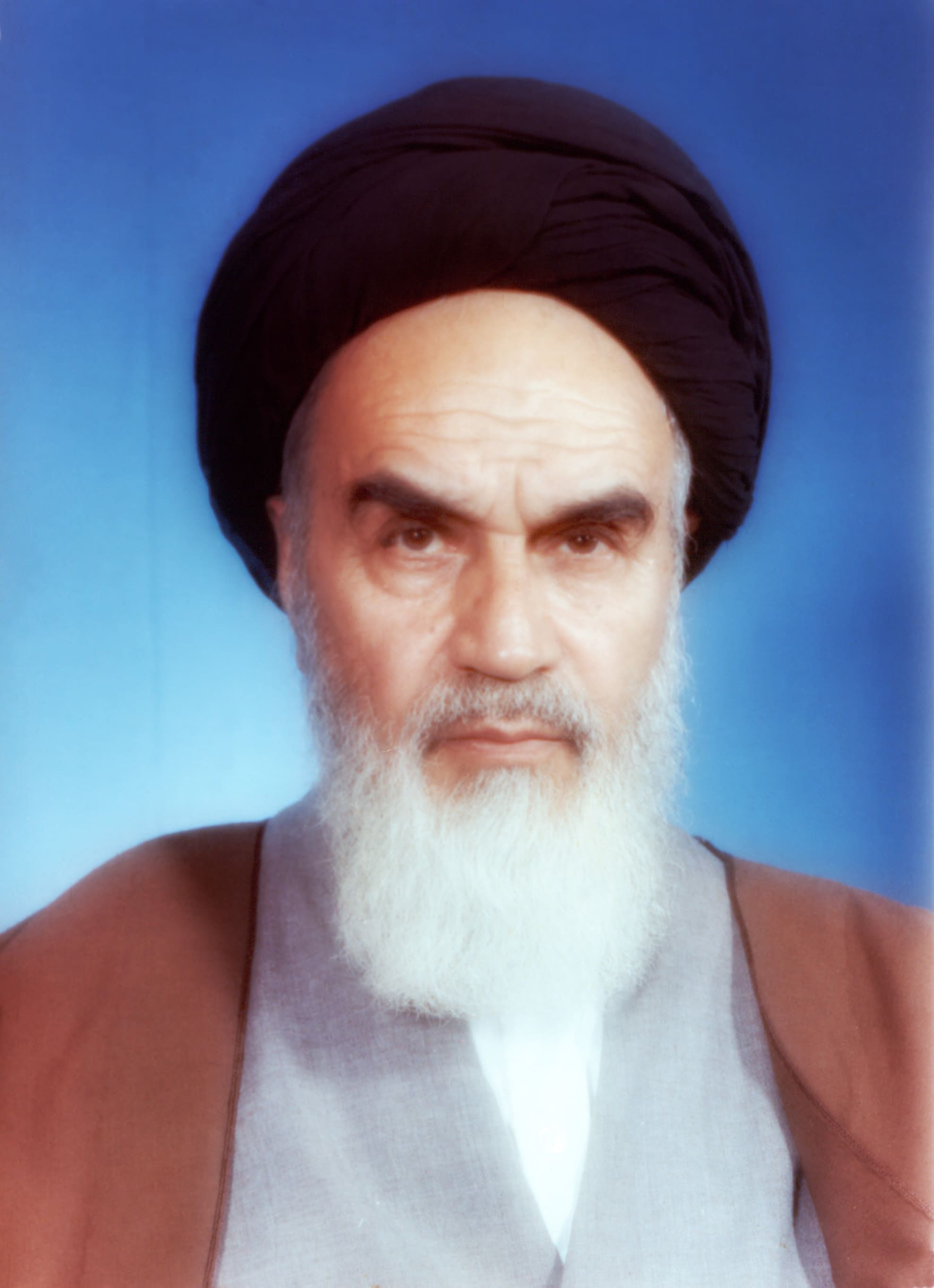

Mohammad Reza's first major dispute with Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a prominent Shi'a cleric, came in 1962 when the Shah altered the laws for swearing in members of municipal councils, allowing non-Muslims to swear oaths upon their own holy books. Khomeini opposed this, feeling that it was a demotion of the primacy of the Quran in a country which was officially Muslim. In what would become Khomeini's modus operandi, he organised demonstrations against the Shah.

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini

In 1963, the Shah launched an ambitious reform programme that became known as the White Revolution. The clergy vociferously opposed the programme, especially the introduction of women's suffrage. Demonstrations against the Shah's rule continued throughout 1963 and 1964, centred in the holy city of Qom, a city full of religious seminaries and the centre of theology in Iran. Clashes with police throughout the period led to over 200 deaths. When criticised for the autocratic nature of his rule, he retorted that "when Persians act like Swedes, then I will act like the King of Sweden". In 1967, he had himself crowned Shahanshah, "King of Kings" or Emperor. He claimed that he chose this moment because he had not deserved it prior, and that "there is no honour in being the Emperor of a poor country". Mohammad Reza felt that Iran was now sufficiently prosperous for him to adopt such a grandiose title. After his coronation, the Shah began to live an ever more grandiose lifestyle. In 1971, he hosted a spectacular commemoration of the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian Empire. Nevertheless, in the 1970s, Iran's economy continued to grow rapidly. With a growth rate equivalent to fast-growing economies such as Turkey, Thailand and the Philippines, Western commentators expected Iran to reach first-world status within a generation. Taking a strong etatist role in economic development, Mohammad Reza supported emergent industrialists, who quickly developed an innovative automotive and engineering sector. The Shah introduced labour laws to ensure that ordinary Iranians gained some benefit from these new, profitable industries. Iran also received generous economic and military aid from the United States during this period, which armed them with some of their most advanced weaponry as a bulwark against the United Arab Republic. As the key remaining US ally in the Persian Gulf region, the Shah exploited his "reverse leverage" against the US, extracting ever greater concessions from the democratic superpower.

By 1975, the Shah had abolished the existing two-party system in favour of the newly established Rastakhiz ("Resurrection") Party. Even prior to the introduction of the one-party state, discontent had simmered below the surface from a number of sources. Some were disaffected labourers, missing out on the nation's newfound prosperity. Others were religious zealots, who saw the White Revolution as Gharbzadegi ("Occidentosis", "Western infection"). A number of guerrilla groups, which blended Marxist and Islamic teachings, began to operate in the regions and cities of Iran. The most significant of these loosely-allied groups was the Mujahedin-e-Khalq (MEK), or People's Mujahedin, which followed the thought of Iranian sociologist Ali Shariati. Shariati divided Shi'ism between 'Black Shi'ism' and 'Red Shi'ism'. Black Shi'ism was deemed to be 'Safavid Shi'ism', which had been instrumentalised to bolster feudalism. Red Shi'ism, which he believed to be the Shi'ism of Ali, was a method of revolutionary praxis, which would bring about the liberation of Third World peoples. The membership of underground organisations swelled, as the oil boom of the 1970s caused runaway inflation and a growing wealth divide. As austerity measures were introduced to bring inflation back under control, those who suffered most were poor migrant workers who had left their homes in the countryside to service the construction boom in Iran's cities, especially Tehran. Ali Shariati died of a heart attack in 1977, but many ordinary Iranians blamed his death of SAVAK.

In early 1978, Ayatollah Khomeini wrote a newspaper article criticising the Shah. In response, the Shah denounced Khomeini as a "British agent" and a "mad poet". Angered by the insult, crowds of religious students clashed with police in Qom. Demonstrations against police brutality then sprang up across major cities throughout the country. The military got involved in suppression of the protests, which only led to an increase in the size of the crowds that took to the streets. On May 10th, army personnel fired upon the residence of Ayatollah Shariatmadari, a moderate cleric who supported democratic reform. The cleric was unharmed, but one of his students was killed. He immediate made public statements calling for the reinstatement of the 1906 Constitution, as well as a shift from an absolute to a constitutional monarchy. Despite unrest, the Shah continued his reforms, hoping for democratic elections to the Majlis to take place in 1979 (albeit with only the Rastakhiz Party represented). Protestors were tried in civilian, rather than military courts, who had traditionally presided over sedition cases. Many were promptly released. The head of SAVAK was replaced by a less hardline chief, and the government entered into negotiations with the moderate clergy, represented by Shariatmadari. By summer, the protests had started to die down.

In August, 422 were killed as four arsonists trapped moviegoers within the Cinema Rex in Abadan and set the theatre ablaze. Khomeini blamed SAVAK and the Shah for the attack, whilst Tehran blamed Islamic Marxists. To this day, no-one is entirely sure who was responsible for the arson. As the economic situation resulted in more layoffs, and as outrage over the Cinema Rex incident boiled over, massive demonstrations manifested in the streets of Tehran. Some protestors went as far as to chant "Burn the Shah!". In the following months, attacks on Western businesses and workers became increasingly frequent. The Shahist regime attempted to appease the public. The Rastakhiz Party was abolished, all other parties were legalised, SAVAK's authority was severely curtailed and 34 of the organisation's commanders dismissed. Casinos and nightclubs were shut down, and the imperial calendar (which had been adopted during the 2500th anniversary and started from that the founding of the Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great) reverted back to the Islamic calendar. The government cracked down on corruption, including within the royal family itself. The government also entered into negotiations with Shariatmadari and National Front leader Karim Sanjabi in order to organise future elections.

On 4th September, during the holiday of Eid-e-Fitr, which marks the end of Ramadan, large marches which had been organised by the clergy occurred in Tehran and provincial centres across the country. Even larger demonstrations followed a few days later. This led the Shah, on 8th September, to declare martial law in the capital, as well as 11 other major cities. All street demonstrations were banned and a curfew imposed. Troops in Tehran were commanded by the notoriously ruthless General Gholam-Ali Oveissi. 5,000 protestors squared off with troops in Jaleh Square, who fired into the crowd, killing 64. Clashes throughout the day claimed even more lives. The Shah was horrified by the events, and ordered troops not to fire on protesters. This did little to rehabilitate his image, however, as he lost ever more credibility through the brutality of his underlings. The next day, 700 workers at Tehran's main oil refinery went on strike. On the 11th, refineries in five other cities were shut down by industrial action. On the 13th, all central government employees in Tehran went on strike simultaneously. By late October, a nationwide general strike brought most major industries to a grinding halt. The Shah attempted to appease workers with general pay increases, to no avail. His advisors began to push him to take forceful measures to bring strikers back into line. As the Shah pondered his options, the situation in Iran turned into even more of a tinderbox. Ayatollah Khomeini, who had been living in exile in Najaf, Iraq, was assassinated by agents of the UAR's State Security Investigations Service, who were concerned that his ideology of Shi'a theocracy could undermine their position in Iraq. Nevertheless, it was widely believed that the culprits of Khomeini's murder was SAVAK[175], and that the assassination was ordered by the Shah.

As news of Khomeini's death broke in Iran, all hell broke loose. Massive rioting engulfed Qom, Tehran and Isfahan. By late October, the military and police had effectively left the University of Tehran to be occupied by student protestors. The opposition acquired weapons from sacking police stations, and began to use them in attacks of police and military personnel. Sanjabi was arrested, and the British embassy in Tehran was burned, along with a number of other Western-owned or Western-inspired businesses (i.e. movie theaters, bars etc.) by youths who had been sent by mullahs from mosques in Southern Tehran. On 6th November, martial law was declared in the Southwestern province of Khuzestan. Navy personnel were used as strikebreakers and oil production rose. A number of public voices, notably that of Mahmoud Taleghani of the Freedom Movement of Iran, denounced the Shah and his government. Taleghani had been strongly influenced by Marxist currents of thought, as well as Shariati's writings. Whilst he personally disliked Khomeini for what he considered his reactionary and autocratic tendencies, he exploited widespread grief to inflame the opposition to the royalist regime. Organised by clerics such as Taleghani, a massive demonstration of two million people, 10% of Tehran's total population, marched onto the streets on muharram, the 2nd December 1978. As Tasu'a and Ashura approached, the Shah began to negotiate with the opposition, releasing Sanjabi and 120 other political prisoners. On 11th December, Ashura, a dozen officers were shot dead at the Lavizan barracks in Tehran by mutinous troops. Fearing further mutinies, many army officers ordered their troops to retire to their barracks. Mashhad, the second-largest city in Iran, was left in the hands of protestors.

On 28th December, prominent National Front leader Shahpour Bakhtiar was appointed Prime Minister. A furious Sanjabi immediately expelled him from the National Front. The Shah had decided that the royal family would go on a holiday, and whilst they were away, Bakhtiar would hold a referendum to determine whether the Iranian people wished to keep the monarchy intact or to transition to a republic. On 16th January, the Shah and his family fled to what would become exile in Lebanon [176]. Bakhtiar dissolved SAVAK and freed all remaining political prisoners, announcing free elections. On 9th February, a rebellion broke out amongst Air Force technicians at Doshan Tappeh AFB in Southeast Tehran. A unit of the Shahist Immortal Guards of the Iranian Imperial Army sought to apprehend the rebels, resulting in a firefight. Soon large crowds emerged in support, building barracades and bringing the rebels supplies, whilst MEK guerrillas seized a weapons factory, distributing 50,000 automatic weapons and ammunition to locals. They then began to storm police stations and army bases, disarming personnel onsite. Seeking to avoid a general bloodbath, commander of Tehran's martial law, General Mehdi Rahimi refused to use his 30,000 strong Immortal Guards to crush the insurrection. On 11th February, all army units were ordered back to their bases, effectively abandoning the country to the various rebels, and the Bakhtiar government collapsed.

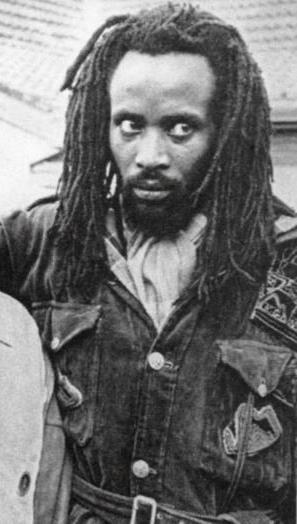

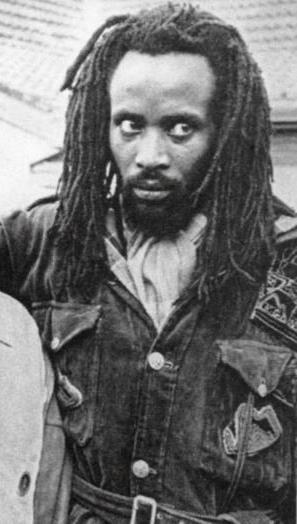

Massoud Rajavi, leader of the Mujahedin-e-Khalq

In the next few days, anarchy reigned in Tehran. Various factions vied over control of city blocks. Whilst the National Front had tried to assert some degree of leadership, they were forced off the streets by the more violent factions. These largely consisted of the followers of various conservative mullahs, who Mohammad Beheshti, Khomeini's close friend and right-hand man, had unsuccessfully tried to reunite under his leadership; against a loose coalition of leftist guerrillas, dominated by the primus inter pares MEK. The Tudeh Party had been largely marginalised by the MEK, seen as it was as a puppet of Soviet interests. Given that the Soviet Union had retained a 30% share of Iranian oil since the crisis in the 1950s, the USSR was seen as just another foreign power seeking to exploit Iran's natural wealth. The MEK, under the leadership of the adept Massoud Rajavi, would systematically seize territory from the fractured Islamists. The left-Islamist coalition was now the most powerful force in Iran. Mahmoud Taleghani provided a spiritual voice and religious legitimacy, whilst Rajavi had managed to bring about a coalition of organisations until his general leadership (including the People's Fedai Guerrillas, National Democratic Front, and the League of Iranian Socialists). Rajavi's right-hand man and commander of the MEK's armed wing, Mousa Khiabani, proved capable of destroying the poorly-organised and equipped fedaiyeen who followed the mullahs. The MEK linked up with other uprisings in Khuzestan, Gilan and elsewhere. By the late quarter of 1980, the Revolutionary Council, headed by Taleghani and Rajavi, had full control over the territories of Iran. In the resultant political wrangling, the MEK purged fully-secular Marxist parties, including Tudeh and Peykar, accusing them of being 'Social-Imperialist Russian spies'. The 30% oil exports to the USSR were halted, causing a diplomatic crisis from which the Soviets eventually backed down, seeking to court the new regime in Tehran. Mahmoud Taleghani was increasingly supported in debates against more conservative clergy, who were ignored and mocked by the MEK regime. In a political masterstroke, Rajavi at once appeased Taleghani and removed him as a potential threat to his leadership by granting political sovereignty to Qom (similar to the Vatican's arrangement with Italy) and establishing Taleghani as the Marja' and Prime Ayatollah of Qom.

===

[174] IOTL, Athens.

[175] IOTL, Khomeini was exiled from Iraq to France after the Shah put significant pressure on the Iraqi government.

[176] IOTL, Egypt.

===

Shahanshah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last monarch of Iran

From the anti-Mossadegh coup of 1953, the Iranian regime was haunted by a crisis of legitimacy. Having overthrown a popular nationalist leader with support from the 'imperialists', the government of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi desperately needed a raison d'être for his autocratic control of the state. He would eventually find this purpose in the modernisation and Westernisation of his country. At first, however, he would be preoccupied with reestablishing monarchical control over the domestic political landscape in Iran. After the coup, the real power behind the throne lay with the Shah's Prime Minister, General Fazlollah Zahedi. At this stage, American and British diplomatic circles, as well as large parts of the Iranian elite, held the Shah in contempt, seeing him as a weak-willed figurehead. Mohammad Reza proved a surprisingly astute politician, and learn to consolidate his power by playing off various factions of the elite against each other. The Shah cultivated an image of a merciful ruler, imprisoning political opponents, such as the supporters of Mossadegh's National Front, and then pardoning them. Many had instead expected a bloody purge. Seeking to broaden his support base, Mohammad Reza ended up adopting many of the policies of the banned National Front, hoping that popular approval could counteract any planned sedition from elites that opposed his reform plans. In 1955, the Shah dismissed General Zahedi and appointed Hossein Ala', who governed as Prime Minister until 1957. In the mid-1950s, the Shah also intended to develop a non-Islamic identity in Iran. In order to do so, he emphasised Iran's Achaemenid imperial past, drawing parallels between himself and Cyrus the Great. He also promised to bring Iranian living standards to the level of the Western nations. To satiate the ulema, who were critical of his de-emphasising of the Islamic past of Iran, he resumed the traditional persecution of Baha'i faithful, razing the primary Baha'i temple in Tehran and passing a law banning Baha'i from publicly congregating.

Privately, the Shah's marriage with his second wife, Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiary, was becoming increasingly strained, as Queen Soraya clashed with Ernest Perron, a homosexual Swiss who was the Shah's personal secretary, confidante and best friend. Perron seemed to enjoy antagonising the Queen, offending her greatly when he arrived at her palace and proceeded to ask lewd questions about her and the Shah's sex life. The marriage between the two would end in 1958, when no remedy could be found to the Queen's infertility. Despite his constant philandering, those close to the Shah would attest that he always loved Soraya, even after their divorce, and she lived out the rest of her days as a wealthy socialite in Paris, her favourite city.

On 27th February 1958, Iranian commander Valiollah Gharani attempted a coup d'etat against the Shah. The coup failed, but it was soon discovered by SAVAK, the Iranian intelligence agency, that Gharani had met with American officials in Tunisia [174]. The Shah demanded that from thereon American officials were not authorised to contact the opposition. Insecure in US support for his regime, in January 1959 the Shah began negotiations for a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union. Receiving furious telegrams from President Eisenhower, in the end the Shah refused to sign an agreement. Soviet dissatisfaction with the Shah's refusal to pledge non-aggression against the Communist superpower led the KGB to attempt to assassinate Mohammad Reza on multiple occasions, nope of which were successful, largely due to the leaking of these plots by KGB station chief in Tehran, Vladimir Kuzichkin.

Mohammad Reza's first major dispute with Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a prominent Shi'a cleric, came in 1962 when the Shah altered the laws for swearing in members of municipal councils, allowing non-Muslims to swear oaths upon their own holy books. Khomeini opposed this, feeling that it was a demotion of the primacy of the Quran in a country which was officially Muslim. In what would become Khomeini's modus operandi, he organised demonstrations against the Shah.

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini

In 1963, the Shah launched an ambitious reform programme that became known as the White Revolution. The clergy vociferously opposed the programme, especially the introduction of women's suffrage. Demonstrations against the Shah's rule continued throughout 1963 and 1964, centred in the holy city of Qom, a city full of religious seminaries and the centre of theology in Iran. Clashes with police throughout the period led to over 200 deaths. When criticised for the autocratic nature of his rule, he retorted that "when Persians act like Swedes, then I will act like the King of Sweden". In 1967, he had himself crowned Shahanshah, "King of Kings" or Emperor. He claimed that he chose this moment because he had not deserved it prior, and that "there is no honour in being the Emperor of a poor country". Mohammad Reza felt that Iran was now sufficiently prosperous for him to adopt such a grandiose title. After his coronation, the Shah began to live an ever more grandiose lifestyle. In 1971, he hosted a spectacular commemoration of the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian Empire. Nevertheless, in the 1970s, Iran's economy continued to grow rapidly. With a growth rate equivalent to fast-growing economies such as Turkey, Thailand and the Philippines, Western commentators expected Iran to reach first-world status within a generation. Taking a strong etatist role in economic development, Mohammad Reza supported emergent industrialists, who quickly developed an innovative automotive and engineering sector. The Shah introduced labour laws to ensure that ordinary Iranians gained some benefit from these new, profitable industries. Iran also received generous economic and military aid from the United States during this period, which armed them with some of their most advanced weaponry as a bulwark against the United Arab Republic. As the key remaining US ally in the Persian Gulf region, the Shah exploited his "reverse leverage" against the US, extracting ever greater concessions from the democratic superpower.

By 1975, the Shah had abolished the existing two-party system in favour of the newly established Rastakhiz ("Resurrection") Party. Even prior to the introduction of the one-party state, discontent had simmered below the surface from a number of sources. Some were disaffected labourers, missing out on the nation's newfound prosperity. Others were religious zealots, who saw the White Revolution as Gharbzadegi ("Occidentosis", "Western infection"). A number of guerrilla groups, which blended Marxist and Islamic teachings, began to operate in the regions and cities of Iran. The most significant of these loosely-allied groups was the Mujahedin-e-Khalq (MEK), or People's Mujahedin, which followed the thought of Iranian sociologist Ali Shariati. Shariati divided Shi'ism between 'Black Shi'ism' and 'Red Shi'ism'. Black Shi'ism was deemed to be 'Safavid Shi'ism', which had been instrumentalised to bolster feudalism. Red Shi'ism, which he believed to be the Shi'ism of Ali, was a method of revolutionary praxis, which would bring about the liberation of Third World peoples. The membership of underground organisations swelled, as the oil boom of the 1970s caused runaway inflation and a growing wealth divide. As austerity measures were introduced to bring inflation back under control, those who suffered most were poor migrant workers who had left their homes in the countryside to service the construction boom in Iran's cities, especially Tehran. Ali Shariati died of a heart attack in 1977, but many ordinary Iranians blamed his death of SAVAK.

In early 1978, Ayatollah Khomeini wrote a newspaper article criticising the Shah. In response, the Shah denounced Khomeini as a "British agent" and a "mad poet". Angered by the insult, crowds of religious students clashed with police in Qom. Demonstrations against police brutality then sprang up across major cities throughout the country. The military got involved in suppression of the protests, which only led to an increase in the size of the crowds that took to the streets. On May 10th, army personnel fired upon the residence of Ayatollah Shariatmadari, a moderate cleric who supported democratic reform. The cleric was unharmed, but one of his students was killed. He immediate made public statements calling for the reinstatement of the 1906 Constitution, as well as a shift from an absolute to a constitutional monarchy. Despite unrest, the Shah continued his reforms, hoping for democratic elections to the Majlis to take place in 1979 (albeit with only the Rastakhiz Party represented). Protestors were tried in civilian, rather than military courts, who had traditionally presided over sedition cases. Many were promptly released. The head of SAVAK was replaced by a less hardline chief, and the government entered into negotiations with the moderate clergy, represented by Shariatmadari. By summer, the protests had started to die down.

In August, 422 were killed as four arsonists trapped moviegoers within the Cinema Rex in Abadan and set the theatre ablaze. Khomeini blamed SAVAK and the Shah for the attack, whilst Tehran blamed Islamic Marxists. To this day, no-one is entirely sure who was responsible for the arson. As the economic situation resulted in more layoffs, and as outrage over the Cinema Rex incident boiled over, massive demonstrations manifested in the streets of Tehran. Some protestors went as far as to chant "Burn the Shah!". In the following months, attacks on Western businesses and workers became increasingly frequent. The Shahist regime attempted to appease the public. The Rastakhiz Party was abolished, all other parties were legalised, SAVAK's authority was severely curtailed and 34 of the organisation's commanders dismissed. Casinos and nightclubs were shut down, and the imperial calendar (which had been adopted during the 2500th anniversary and started from that the founding of the Persian Empire by Cyrus the Great) reverted back to the Islamic calendar. The government cracked down on corruption, including within the royal family itself. The government also entered into negotiations with Shariatmadari and National Front leader Karim Sanjabi in order to organise future elections.

On 4th September, during the holiday of Eid-e-Fitr, which marks the end of Ramadan, large marches which had been organised by the clergy occurred in Tehran and provincial centres across the country. Even larger demonstrations followed a few days later. This led the Shah, on 8th September, to declare martial law in the capital, as well as 11 other major cities. All street demonstrations were banned and a curfew imposed. Troops in Tehran were commanded by the notoriously ruthless General Gholam-Ali Oveissi. 5,000 protestors squared off with troops in Jaleh Square, who fired into the crowd, killing 64. Clashes throughout the day claimed even more lives. The Shah was horrified by the events, and ordered troops not to fire on protesters. This did little to rehabilitate his image, however, as he lost ever more credibility through the brutality of his underlings. The next day, 700 workers at Tehran's main oil refinery went on strike. On the 11th, refineries in five other cities were shut down by industrial action. On the 13th, all central government employees in Tehran went on strike simultaneously. By late October, a nationwide general strike brought most major industries to a grinding halt. The Shah attempted to appease workers with general pay increases, to no avail. His advisors began to push him to take forceful measures to bring strikers back into line. As the Shah pondered his options, the situation in Iran turned into even more of a tinderbox. Ayatollah Khomeini, who had been living in exile in Najaf, Iraq, was assassinated by agents of the UAR's State Security Investigations Service, who were concerned that his ideology of Shi'a theocracy could undermine their position in Iraq. Nevertheless, it was widely believed that the culprits of Khomeini's murder was SAVAK[175], and that the assassination was ordered by the Shah.

As news of Khomeini's death broke in Iran, all hell broke loose. Massive rioting engulfed Qom, Tehran and Isfahan. By late October, the military and police had effectively left the University of Tehran to be occupied by student protestors. The opposition acquired weapons from sacking police stations, and began to use them in attacks of police and military personnel. Sanjabi was arrested, and the British embassy in Tehran was burned, along with a number of other Western-owned or Western-inspired businesses (i.e. movie theaters, bars etc.) by youths who had been sent by mullahs from mosques in Southern Tehran. On 6th November, martial law was declared in the Southwestern province of Khuzestan. Navy personnel were used as strikebreakers and oil production rose. A number of public voices, notably that of Mahmoud Taleghani of the Freedom Movement of Iran, denounced the Shah and his government. Taleghani had been strongly influenced by Marxist currents of thought, as well as Shariati's writings. Whilst he personally disliked Khomeini for what he considered his reactionary and autocratic tendencies, he exploited widespread grief to inflame the opposition to the royalist regime. Organised by clerics such as Taleghani, a massive demonstration of two million people, 10% of Tehran's total population, marched onto the streets on muharram, the 2nd December 1978. As Tasu'a and Ashura approached, the Shah began to negotiate with the opposition, releasing Sanjabi and 120 other political prisoners. On 11th December, Ashura, a dozen officers were shot dead at the Lavizan barracks in Tehran by mutinous troops. Fearing further mutinies, many army officers ordered their troops to retire to their barracks. Mashhad, the second-largest city in Iran, was left in the hands of protestors.

On 28th December, prominent National Front leader Shahpour Bakhtiar was appointed Prime Minister. A furious Sanjabi immediately expelled him from the National Front. The Shah had decided that the royal family would go on a holiday, and whilst they were away, Bakhtiar would hold a referendum to determine whether the Iranian people wished to keep the monarchy intact or to transition to a republic. On 16th January, the Shah and his family fled to what would become exile in Lebanon [176]. Bakhtiar dissolved SAVAK and freed all remaining political prisoners, announcing free elections. On 9th February, a rebellion broke out amongst Air Force technicians at Doshan Tappeh AFB in Southeast Tehran. A unit of the Shahist Immortal Guards of the Iranian Imperial Army sought to apprehend the rebels, resulting in a firefight. Soon large crowds emerged in support, building barracades and bringing the rebels supplies, whilst MEK guerrillas seized a weapons factory, distributing 50,000 automatic weapons and ammunition to locals. They then began to storm police stations and army bases, disarming personnel onsite. Seeking to avoid a general bloodbath, commander of Tehran's martial law, General Mehdi Rahimi refused to use his 30,000 strong Immortal Guards to crush the insurrection. On 11th February, all army units were ordered back to their bases, effectively abandoning the country to the various rebels, and the Bakhtiar government collapsed.

Massoud Rajavi, leader of the Mujahedin-e-Khalq

In the next few days, anarchy reigned in Tehran. Various factions vied over control of city blocks. Whilst the National Front had tried to assert some degree of leadership, they were forced off the streets by the more violent factions. These largely consisted of the followers of various conservative mullahs, who Mohammad Beheshti, Khomeini's close friend and right-hand man, had unsuccessfully tried to reunite under his leadership; against a loose coalition of leftist guerrillas, dominated by the primus inter pares MEK. The Tudeh Party had been largely marginalised by the MEK, seen as it was as a puppet of Soviet interests. Given that the Soviet Union had retained a 30% share of Iranian oil since the crisis in the 1950s, the USSR was seen as just another foreign power seeking to exploit Iran's natural wealth. The MEK, under the leadership of the adept Massoud Rajavi, would systematically seize territory from the fractured Islamists. The left-Islamist coalition was now the most powerful force in Iran. Mahmoud Taleghani provided a spiritual voice and religious legitimacy, whilst Rajavi had managed to bring about a coalition of organisations until his general leadership (including the People's Fedai Guerrillas, National Democratic Front, and the League of Iranian Socialists). Rajavi's right-hand man and commander of the MEK's armed wing, Mousa Khiabani, proved capable of destroying the poorly-organised and equipped fedaiyeen who followed the mullahs. The MEK linked up with other uprisings in Khuzestan, Gilan and elsewhere. By the late quarter of 1980, the Revolutionary Council, headed by Taleghani and Rajavi, had full control over the territories of Iran. In the resultant political wrangling, the MEK purged fully-secular Marxist parties, including Tudeh and Peykar, accusing them of being 'Social-Imperialist Russian spies'. The 30% oil exports to the USSR were halted, causing a diplomatic crisis from which the Soviets eventually backed down, seeking to court the new regime in Tehran. Mahmoud Taleghani was increasingly supported in debates against more conservative clergy, who were ignored and mocked by the MEK regime. In a political masterstroke, Rajavi at once appeased Taleghani and removed him as a potential threat to his leadership by granting political sovereignty to Qom (similar to the Vatican's arrangement with Italy) and establishing Taleghani as the Marja' and Prime Ayatollah of Qom.

===

[174] IOTL, Athens.

[175] IOTL, Khomeini was exiled from Iraq to France after the Shah put significant pressure on the Iraqi government.

[176] IOTL, Egypt.

Last edited:

First of all, good to see you back!

Second of all, left-Islamist Iran is something that you rarely see in alt-history, since the general assumption is that Tudeh and the pro-Soviet field is the default winner in any scenario that doesn't end with the regime of the Ayatollahs rising to absolute power. Bold move, I really hope to see more from this political anomaly.

Second of all, left-Islamist Iran is something that you rarely see in alt-history, since the general assumption is that Tudeh and the pro-Soviet field is the default winner in any scenario that doesn't end with the regime of the Ayatollahs rising to absolute power. Bold move, I really hope to see more from this political anomaly.

Massoud Rajavi, leader of the Mujahedin-e-Khalq

In the next few days, anarchy reigned in Tehran. Various factions vied over control of city blocks. Whilst the National Front had tried to assert some degree of leadership, they were forced off the streets by the more violent factions. These largely consisted of the followers of various conservative mullahs, who Mohammad Beheshti, Khomeini's close friend and right-hand man, had unsuccessfully tried to reunite under his leadership; against a loose coalition of leftist guerrillas, dominated by the primus inter pares MEK. The Tudeh Party had been largely marginalised by the MEK, seen as it was as a puppet of Soviet interests. Given that the Soviet Union had retained a 30% share of Iranian oil since the crisis in the 1950s, the USSR was seen as just another foreign power seeking to exploit Iran's natural wealth. The MEK, under the leadership of the adept Massoud Rajavi, would systematically seize territory from the fractured Islamists. The left-Islamist coalition was now the most powerful force in Iran. Mahmoud Taleghani provided a spiritual voice and religious legitimacy, whilst Rajavi had managed to bring about a coalition of organisations until his general leadership (including the People's Fedai Guerrillas, National Democratic Front, and the League of Iranian Socialists). Rajavi's right-hand man and commander of the MEK's armed wing, Mousa Khiabani, proved capable of destroying the poorly-organised and equipped fedaiyeen who followed the mullahs. The MEK linked up with other uprisings in Khuzestan, Gilan and elsewhere. By the late quarter of 1980, the Revolutionary Council, headed by Taleghani and Rajavi, had full control over the territories of Iran. In the resultant political wrangling, the MEK purged fully-secular Marxist parties, including Tudeh and Peykar, accusing them of being 'Social-Imperialist Russian spies'. The 30% oil exports to the USSR were halted, causing a diplomatic crisis from which the Soviets eventually backed down, seeking to court the new regime in Tehran. Mahmoud Taleghani was increasingly supported in debates against more conservative clergy, who were ignored and mocked by the MEK regime. In a political masterstroke, Rajavi at once appeased Taleghani and removed him as a potential threat to his leadership by granting political sovereignty to Qom (similar to the Vatican's arrangement with Italy) and establishing Taleghani as the Marja' and Prime Ayatollah of Qom.

===

[174] IOTL, Athens.

[175] IOTL, Khomeini was exiled from Iraq to France after the Shah put significant pressure on the Iraqi government.

[176] IOTL, Egypt.

I hope they will not reach the reactionary laws of the Shiite Fascists of Khomeini.First of all, good to see you back!

Second of all, left-Islamist Iran is something that you rarely see in alt-history, since the general assumption is that Tudeh and the pro-Soviet field is the default winner in any scenario that doesn't end with the regime of the Ayatollahs rising to absolute power. Bold move, I really hope to see more from this political anomaly.

Damn, if only @GoulashComrade was here. Red Shia Iran is something that he is planning for his Somalia timeline.

Chapter 73: Under the Shadow of Shwedagon (Burma until 1980)

For more information about Burma (1950s), see: https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...rnative-cold-war.280530/page-22#post-11194220

===

Burma's future looked relatively promising at the beginning of the 1960s. Whilst domestic instability had resulted in a myriad of armed rebellions amongst the various minority groups of the country, the "Father of the Nation" Aung San had managed to maintain a grand coalition under the leadership of the AFPFL, including the White Flag Communists and the Buddhist Arakanese followers of U Seinda. The Tatmadaw, the armed forces of the republic, gradually suppressed groups such as the Rohingya mujahideen and convinced a number of Shan groups to lay down their arms. With the majority of the major ethnic groups involved in the political process, opposition to central government control was largely confined to the Northern highlands. The Tatmadaw retained a strong garrison in these frontier regions, but the local commanders were essentially independent, and became involved in the profitable smuggling and opium trades which dominated the border regions with China and Thailand.

Aung San himself had become the sole major political figure in the country with the suicide of U Saw. A number of army commanders and civilian politicians were concerned by the degree of communist influence in the government, but were content with Aung San's ability to maintain a status quo that balanced the interests of the various factions. In mid-1962, Aung San was briefly hospitalised as a result of a sudden illness, with the leadership of the civilian government passing to U Nu in the interim. U Nu bungled an economic crisis arising from a fall in rice prices, which undercut social welfare programmes, failed to slow runaway inflation and put significant pressure on working urban Burmese. Twin demonstrations in Mandalay and Rangoon, organised by the Burma Workers Party on behalf of unpaid workers, quickly degenerated into crisis. Ne Win, the Chief of Staff of the Tatmadaw, blamed the demonstrations on a communist conspiracy, which he claimed was backed by influential commander Bo Zeya and other members of the Thirty Comrades, Kyaw Zaw, Bo Yan Aung and leader of the CPB Thakin Than Tun. U Nu invited Ne Win to head a military government until the crisis had been handled. Instituting martial law in all the urban areas of the country and implementing strict curfews, the Tatmadaw dispersed the more intractable elements of the demonstrators by force. By February 1963, Aung San had miraculously made a full recovery from the severe fevers which had afflicted him the previous year. It was announced by U Nu that full civilian control of the functions of government would be taken up in June, with parliamentary elections taking place in July to determine the composition of government. It was widely expected that Aung San would return to the leadership of the nation. The night before civilian governance was to be restored, the Tatmadaw seized key government and media buildings in towns throughout Burma. An address written by Ne Win was announced over all radio stations in the country.

General Ne Win, putschist and leader of Burma after the coup of 1963

"Burmese, this is a message from your faithful chief of staff. It has been the Tatmadaw's duty in the past months to ensure the integrity of the Burmese nation and the protection of its citizens from elements which seek to harm our glorious nation. The government of the politicians is ridden with corruption, incompetence and cowardice. They do nothing to punish the communists whose mission it is to overturn our independence and bring us into the servitude of the Chinese and Vietnamese. These elements are courted by the soft leaders who huddle in their palaces. We could not allow this. We promise that the Tatmadaw will protect Burmese peace, independence and dignity. It is we who will cleanse this nation of corrosive elements and who will guide the destiny of the nation with decisive action and wise foresight. The reintroduction of civilian government is henceforth suspended. The military will continue to govern on behalf of the peoples of Burma until such time as we are satisfied that our help is no longer needed. From now on, the Union Revolutionary Council will be the sole fount of all political authority in this beautiful land."

Aung San disappeared, his whereabouts unknown. U Nu was imprisoned. Army units associated with Bo Zeya resisted the attempted disarmament by the main body of the Tatmadaw, retreating north to join elements of the CPB who had taken refuge amongst the Wa and Kokang in the north. The CPB immediately entered into open revolt against army rule. The numerous rebel groups of the Shan separatists largely reactivated in defiance of Ne Win's seizure of power, and of the various ethnic groups, only the Bamar and Arakanese stayed docile. A number of political figures, including Aung San's older brother Aung Than (who headed the National United Front party) and ordinary supporters of the CPB and Worker's Party were sent in Great Coco Island in the Andaman chain. Ne Win introduced a new range of economic and political reforms, dubbed the "Burmese Way to Socialism". The programme was intended to allow for self-reliance for Burma and to promote national unity. All political parties were banned, with the exception of the new state-sponsored party, the Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP). Some of the instituted policies legitimately aided the Burmese poor. Medical care was made entirely free and a new public education system was introduced, with a particular focus on the extermination of illiteracy. He also introduced important laws to limit usury and to regulate landlordship. However, the overall programme was an abysmal failure. The black market began to take an ever-bigger share of economic activity in the country, with smuggling rampant. Meanwhile government coffers continued to empty. In an attempt to combat inflation, the Union Revolutionary Council declared 100 and 50 kyat notes to no longer be legal tender, to be replaced by 45 and 90 kyat notes (Ne Win considered the number 9 to be particularly auspicious). Only a small amount of compensation was provided to those with their savings in banks, with official skimming most of that money into their own pockets. The vast majority of Burmese, whose savings were largely kept 'under the mattress' had their life savings wiped out overnight. Furious, the Kayan revolted in response to this development.

Despite having Chinese ancestry himself, Ne Win introduced policies which disproportionately affected ethnic Chinese negatively. The Enterprise Nationalisation Law brought a number of industries under state control, and no new factories would be built under Ne Win's rule. Many of the entrepreneurs who were dispossessed were Chinese, and laws were introduced limiting the citizenship status of Burmese Chinese, making them ineligible for many forms of government support. Chinese language education was banned, and the Chinese were often scapegoated for economic problems. As a result, Chinese-owned businesses and homes were regularly targeted in riots. The Ne Win regime expanded this xenophobia in general. Fearful of corrupting foreign influence, they introduced heavy censorship, and visas for foreigners were limited to 24 hours. They allowed some travel abroad for Burmese, but only students and technicians, who were sent to the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe for training. Yugoslavia in particular became a close ally, providing arms and technical training for the regime.

Whilst Ne Win had visited Beijing, and the Chinese leadership assured him that they were not supporting the Communist Party of Burma's insurgency in the border regions with China, relations became increasingly strained during the Cultural Revolution. For some time during the revolution, the CPB had actually become less active, as Thakin Than Tun, leader of the CPB, had himself launched his own 'cultural revolution' in the party, which quickly spiralled under control. Whilst Than Tun, along with the other leadership of the CPB (including the so-called 'Peking returnees' who returned from exile in 1966 for failed peace talks with Ne Win) managed to bring the party back under control, the PRC began to initiate clandestine support for the CPB. In 1968, Thakin Than Tun was assassinated by a young cadre, who soon defected to the central government.

Ne Win's apparent detente with China and the announcement of the Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma was viewed with increasing concern in Bangkok and Delhi. Those two states, with staunchly anti-communist governments and a fair of 'Red expansionism' began to become involved with the internal politics of Burma. The Thai government began covert support for the Shan State Army, whilst Bharati diplomats began to get into contact with various military figures, particularly those that came from a Buddhist background. According to the "ideology of the Dharma" which was state policy in Bharatiya and increasingly gaining traction in Thailand, Burma was a key strategic area for the creation of a cordon sanitaire limiting the spread of communism and precluding its extension into South and Southeast Asia.

Throughout the 1970s, the economic stagnation of Burma continued, whilst insurgent groups gained traction throughout the country. Arakanese nationalists, supported by Bharatiya, engaged in communal violence against the Rohingya. The government stayed aloof from these disturbances, essentially allowing the Arakanese to wipe out most of the Rohingya population in Burma. The remainders largely fled to Bangladesh. In 1973, the Chinese began an undeclared invasion of northern Burma, after the Ne Win government ousted the CPB from their central Burmese base at Pyinmana. The CPB increased their activity in the north, whilst Wa state become de facto governed by the Chinese. Threatened by the Chinese incursion, the Shan State Army asked for direct intervention and protection from Thailand, which would come to be with the full collapse of the Ne Win government in 1983 at the hands of the Bharati-backed coup in Rangoon.

===

Burma's future looked relatively promising at the beginning of the 1960s. Whilst domestic instability had resulted in a myriad of armed rebellions amongst the various minority groups of the country, the "Father of the Nation" Aung San had managed to maintain a grand coalition under the leadership of the AFPFL, including the White Flag Communists and the Buddhist Arakanese followers of U Seinda. The Tatmadaw, the armed forces of the republic, gradually suppressed groups such as the Rohingya mujahideen and convinced a number of Shan groups to lay down their arms. With the majority of the major ethnic groups involved in the political process, opposition to central government control was largely confined to the Northern highlands. The Tatmadaw retained a strong garrison in these frontier regions, but the local commanders were essentially independent, and became involved in the profitable smuggling and opium trades which dominated the border regions with China and Thailand.

Aung San himself had become the sole major political figure in the country with the suicide of U Saw. A number of army commanders and civilian politicians were concerned by the degree of communist influence in the government, but were content with Aung San's ability to maintain a status quo that balanced the interests of the various factions. In mid-1962, Aung San was briefly hospitalised as a result of a sudden illness, with the leadership of the civilian government passing to U Nu in the interim. U Nu bungled an economic crisis arising from a fall in rice prices, which undercut social welfare programmes, failed to slow runaway inflation and put significant pressure on working urban Burmese. Twin demonstrations in Mandalay and Rangoon, organised by the Burma Workers Party on behalf of unpaid workers, quickly degenerated into crisis. Ne Win, the Chief of Staff of the Tatmadaw, blamed the demonstrations on a communist conspiracy, which he claimed was backed by influential commander Bo Zeya and other members of the Thirty Comrades, Kyaw Zaw, Bo Yan Aung and leader of the CPB Thakin Than Tun. U Nu invited Ne Win to head a military government until the crisis had been handled. Instituting martial law in all the urban areas of the country and implementing strict curfews, the Tatmadaw dispersed the more intractable elements of the demonstrators by force. By February 1963, Aung San had miraculously made a full recovery from the severe fevers which had afflicted him the previous year. It was announced by U Nu that full civilian control of the functions of government would be taken up in June, with parliamentary elections taking place in July to determine the composition of government. It was widely expected that Aung San would return to the leadership of the nation. The night before civilian governance was to be restored, the Tatmadaw seized key government and media buildings in towns throughout Burma. An address written by Ne Win was announced over all radio stations in the country.

General Ne Win, putschist and leader of Burma after the coup of 1963

"Burmese, this is a message from your faithful chief of staff. It has been the Tatmadaw's duty in the past months to ensure the integrity of the Burmese nation and the protection of its citizens from elements which seek to harm our glorious nation. The government of the politicians is ridden with corruption, incompetence and cowardice. They do nothing to punish the communists whose mission it is to overturn our independence and bring us into the servitude of the Chinese and Vietnamese. These elements are courted by the soft leaders who huddle in their palaces. We could not allow this. We promise that the Tatmadaw will protect Burmese peace, independence and dignity. It is we who will cleanse this nation of corrosive elements and who will guide the destiny of the nation with decisive action and wise foresight. The reintroduction of civilian government is henceforth suspended. The military will continue to govern on behalf of the peoples of Burma until such time as we are satisfied that our help is no longer needed. From now on, the Union Revolutionary Council will be the sole fount of all political authority in this beautiful land."

Aung San disappeared, his whereabouts unknown. U Nu was imprisoned. Army units associated with Bo Zeya resisted the attempted disarmament by the main body of the Tatmadaw, retreating north to join elements of the CPB who had taken refuge amongst the Wa and Kokang in the north. The CPB immediately entered into open revolt against army rule. The numerous rebel groups of the Shan separatists largely reactivated in defiance of Ne Win's seizure of power, and of the various ethnic groups, only the Bamar and Arakanese stayed docile. A number of political figures, including Aung San's older brother Aung Than (who headed the National United Front party) and ordinary supporters of the CPB and Worker's Party were sent in Great Coco Island in the Andaman chain. Ne Win introduced a new range of economic and political reforms, dubbed the "Burmese Way to Socialism". The programme was intended to allow for self-reliance for Burma and to promote national unity. All political parties were banned, with the exception of the new state-sponsored party, the Burma Socialist Programme Party (BSPP). Some of the instituted policies legitimately aided the Burmese poor. Medical care was made entirely free and a new public education system was introduced, with a particular focus on the extermination of illiteracy. He also introduced important laws to limit usury and to regulate landlordship. However, the overall programme was an abysmal failure. The black market began to take an ever-bigger share of economic activity in the country, with smuggling rampant. Meanwhile government coffers continued to empty. In an attempt to combat inflation, the Union Revolutionary Council declared 100 and 50 kyat notes to no longer be legal tender, to be replaced by 45 and 90 kyat notes (Ne Win considered the number 9 to be particularly auspicious). Only a small amount of compensation was provided to those with their savings in banks, with official skimming most of that money into their own pockets. The vast majority of Burmese, whose savings were largely kept 'under the mattress' had their life savings wiped out overnight. Furious, the Kayan revolted in response to this development.

Despite having Chinese ancestry himself, Ne Win introduced policies which disproportionately affected ethnic Chinese negatively. The Enterprise Nationalisation Law brought a number of industries under state control, and no new factories would be built under Ne Win's rule. Many of the entrepreneurs who were dispossessed were Chinese, and laws were introduced limiting the citizenship status of Burmese Chinese, making them ineligible for many forms of government support. Chinese language education was banned, and the Chinese were often scapegoated for economic problems. As a result, Chinese-owned businesses and homes were regularly targeted in riots. The Ne Win regime expanded this xenophobia in general. Fearful of corrupting foreign influence, they introduced heavy censorship, and visas for foreigners were limited to 24 hours. They allowed some travel abroad for Burmese, but only students and technicians, who were sent to the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe for training. Yugoslavia in particular became a close ally, providing arms and technical training for the regime.

Whilst Ne Win had visited Beijing, and the Chinese leadership assured him that they were not supporting the Communist Party of Burma's insurgency in the border regions with China, relations became increasingly strained during the Cultural Revolution. For some time during the revolution, the CPB had actually become less active, as Thakin Than Tun, leader of the CPB, had himself launched his own 'cultural revolution' in the party, which quickly spiralled under control. Whilst Than Tun, along with the other leadership of the CPB (including the so-called 'Peking returnees' who returned from exile in 1966 for failed peace talks with Ne Win) managed to bring the party back under control, the PRC began to initiate clandestine support for the CPB. In 1968, Thakin Than Tun was assassinated by a young cadre, who soon defected to the central government.

Ne Win's apparent detente with China and the announcement of the Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma was viewed with increasing concern in Bangkok and Delhi. Those two states, with staunchly anti-communist governments and a fair of 'Red expansionism' began to become involved with the internal politics of Burma. The Thai government began covert support for the Shan State Army, whilst Bharati diplomats began to get into contact with various military figures, particularly those that came from a Buddhist background. According to the "ideology of the Dharma" which was state policy in Bharatiya and increasingly gaining traction in Thailand, Burma was a key strategic area for the creation of a cordon sanitaire limiting the spread of communism and precluding its extension into South and Southeast Asia.

Throughout the 1970s, the economic stagnation of Burma continued, whilst insurgent groups gained traction throughout the country. Arakanese nationalists, supported by Bharatiya, engaged in communal violence against the Rohingya. The government stayed aloof from these disturbances, essentially allowing the Arakanese to wipe out most of the Rohingya population in Burma. The remainders largely fled to Bangladesh. In 1973, the Chinese began an undeclared invasion of northern Burma, after the Ne Win government ousted the CPB from their central Burmese base at Pyinmana. The CPB increased their activity in the north, whilst Wa state become de facto governed by the Chinese. Threatened by the Chinese incursion, the Shan State Army asked for direct intervention and protection from Thailand, which would come to be with the full collapse of the Ne Win government in 1983 at the hands of the Bharati-backed coup in Rangoon.

Last edited:

Chapter 74: A Pack of Hyenas - East Africa and the Great Lakes Region (Until 1980)

For more information about the balkanisation of Kenya, see: https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...ternative-cold-war.280530/page-7#post-9096189

and

https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...ternative-cold-war.280530/page-7#post-9148081

===

Having collapsed into a number of rival statelets at the end of the 1950s, the various successors of the British Kenya territory spent the early 1960s aligning themselves with various regional and international powers.

In a prolonged civil war that commenced immediately following independence, the Kenyan Peoples' Popular Front (KPPF) gradually drove out the traditionalist Kirinyaga National Union (KNU), which sought refuge with the pan-Africanist government of Julius Nyerere in Tanganyika. Isolated and surrounded by relatively hostile powers, the KPPF sought outside support. They attempted to court the Soviet Union, but the Khrushchev government, relatively uninterested by African affairs and preoccupied with events elsewhere, refused to support the KPPF. However, the KPPF found a more sympathetic ear with the Mao regime in China. Chinese support in arms and money entered Kirinyaga-Kenyaland via the dirt roads along the border with Tanganyika, a state which hosted exiled opposition leaders Stanley Mathenge, Waruhiu Itote and Musa Mwariama of the KNU. This precarious strategic situation fueled paranoia in the ruling KPPF junta, which boiled over as a result of the political aftermath of the 1965 famine, where thousands starved to death as a result of poorly-handled land reform. In a number of areas, local farmers and pastoralists violently resisted the requisition of their yield, resulting in the burning down of a number of villages by government militia. As his government became increasingly shaky, President Bildad Kaggia became increasingly reliant on Interior Minister Dedan Kimathi to maintain rule by force. Claiming that the opposition were "imperialist stooges" and referring to the hopelessly outnumbered armed peasants as "askaris", Kaggia introduced martial law. In March 1966, seeking to take advantage of turmoil in Kirinyaga-Kenyaland, and seeking to prove the effectiveness of their new army, which had expelled British officers, Nyerere ordered an incursion into Kirinyaga-Kenyaland in order to topple the KPPF and put the KNU troika into power.

Marching over the border, supported by a small number of armoured cars, the KNU militia with support from the Tanganyikan People's Defence Force were engaged by Kirinyagan troops which held the line in the Namanga Hills. Kimathi immediately travelled to the region to take total command. Rather than attempting to destroy the enemy forces, Kimathi successfully drew the attackers into the forested hills, where they were unable to take advantage of the Tanganyikans' firepower superiority due to the broken terrain and poor lines of sight. Armoured cars were incapable of moving within the elevated cloud forest, constricted to the poor roads between the two nations, where they were susceptible to ambush by Maasai warriors armed with RPGs. Reinforcements by Gĩkũyũ troops from central Kirinyaga put huge pressure on the poorly-trained invading forces, which collapsed and fled across the border back into Tanganyika. Kirinyaga troops engaged in a number of cross-border raids, which were notorious for the scale of sexual violence. These attacks halted when Chinese diplomats informed the KPPF junta that any attempt to invade Tanganyika would result in the cession of support from the PRC. A ceasefire ensued, with the Zanzibari revolutionary government brokering peace between the warring states. One major result of the war was that Kirinyaga was forced to turn to the Swahili Coast for trade with the outside world. Despite distaste for Kirinyaga and its government (intensified by Mau Mau attacks on Mijikenda villages during the independence struggle), Kirinyaga was allowed to trade out of Swahili ports in exchange for major dues. This arrangement would continue, with Kirinyaga becoming increasingly dependent on petroleum products imported from the Arab world via Swahili ports. In 1969, after political maneuvering, Dedan Kimathi took advantage of his status as victor of the war against Tanganyika to overthrow Kaggia in a coup, having forged documents falsely claiming that he was taking money from the British. Throughout the 1970s, Kirinyaga continued to stagnate, with Kimathi ruling increasingly despotically, taking a number of concubines and embezzling money through Swiss bank accounts. Opposition was dealt with viciously, and aside from state-dominated trade with commercial cartels in the Swahili Coast, the state pursued autarky. Unlike other socialist states, which at least pushed education and full-employment, the Kirinyagan state kept people in agrarian occupations. As a result, they had one of the worst literacy rates in Africa. Only government bureaucrats and military families were given a state-sponsored education. Starvation was common, as the increasingly militarised state was funded by the requisitioning of grain.

Dedan Kimathi, victor of the Kirinyaga-Tanganyika War and later President of Kirinyaga

In the north, the Rift Valley Republic grew increasingly close to the Ethiopian Empire. This was as a result of the creation of the Greater Rift Valley Community, whose first major project was the construction of a major American-funded and American-constructed highway system centred on Addis Ababa beginning in 1969. One circuit of the system ran through Lodwar on the way to Kisumu in Kavirondo. Later expansions would further integrate the Rift Valley Republic with the East African pro-Western bloc by establishing connections to Marsabit and Malakal. Commercial activity intensified as a result, with low-interest loans underwritten by the Imperial Solomonic Bank (ISB) of Ethiopia, which rapidly became the largest financial entity in East Africa. The bank's emblem, the Conquering Lion of Judah, became ubiquitous from the Great Lakes to Juba in Equatoria. Through the 1970s, Rift Valley integration with Ethiopia also began in the security sphere, the Rift Valley Defence Force being trained by Ethiopian officers and armed with American weaponry. A mutual defense treaty was signed in 1974 as a counter against the potential threat of Somali irredentism along the frontier. Whilst most Somali-inhabited areas of Kenya were absorbed by Mogadishu, a few disputed villages remained governed from Lodwar.

The Kingdom of Kavirondo, the elective monarchy on the eastern shore of Lake Victoria, was lead by ker Oginga Odinga throughout this period. Unsurprisingly, given that Odinga was a businessman, head of the Luo Thrift and Trading Corporation, the government was dominated by his family members. His sons Raila and Oburu Odinga were being educated in West Germany to prepare for eventual rule. The economic life of Kavirondo was shaped from the mid-1960s onwards by Barack Obama, who had returned from study at University of Hawaii and Harvard with his American wife Ruth Beatrice Baker. Obama promoted economic cooperation with the United States and Ethiopia, convincing Oginga Odinga to sign off on joining the Greater Rift Valley Community, which paid off virtually immediately with the construction of the Jackson highway which connected Kisumu with the Ethiopian port of Massawa and the outside world. Kavirondo become one of the wealthiest nations in central Africa, relatively peaceful and stable, with a burgeoning middle class, although nepotism and corruption remained a major issue. Politically, Kavirondo focused on relations with the other countries surrounding Lake Victoria. In reaction to Idi Amin's alignment with the Soviet Union, Kavirondo built up its armed forces with relatively modern Western weaponry. They sheltered Tutsis which escaped persecution in Rwanda and Burundi, building strong ties with the Tutsi monarchists. This support for the Tutsis was borne out of realpolitik, rather than humanitarian considerations. The Congolese government of Patrice Lumumba supported Hutu revolutionaries in Rwanda and Burundi in order to spread socialist control in Central Africa, with the Kavirondo elite viewing the expulsion of the Tutsis as a class struggle, not an ethnic struggle. This dynamic would turn Burundi and Rwanda into a battlefield for Kavirondo's proxy conflicts with Uganda and Congo.

Ker Oginga Odinga, monarch of Kavirondo

The Swahili Coast was an oddity in East Africa. Relatively wealthy, the Swahili commercial elites of the state opportunistically exploited shifts in the regional economic and political situation. Attempting to utilise their traditional position as an entrepot to the East African interior, they charged severe transit dues for the transport of goods into Kirinyaga. However, the inability of goods to be transported via Kirinyaga to other markets cut the Swahili Coast off from the lucrative Great Lakes region, imports to which were dominated by Massawa. As a result, the Swahili Coast began to rely on blockade running and money laundering/tax evasion, particularly with regards to becoming an intermediary with South Africa for countries unwilling or unable to openly trade with the apartheid regime. The Mijikenda of the interior littoral remained relatively undeveloped, with some migration to Mombasa and Malindi, where they typically performed menial jobs such as sanitation and housekeeping for the urban Swahilis.

and

https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...ternative-cold-war.280530/page-7#post-9148081

===

Having collapsed into a number of rival statelets at the end of the 1950s, the various successors of the British Kenya territory spent the early 1960s aligning themselves with various regional and international powers.

In a prolonged civil war that commenced immediately following independence, the Kenyan Peoples' Popular Front (KPPF) gradually drove out the traditionalist Kirinyaga National Union (KNU), which sought refuge with the pan-Africanist government of Julius Nyerere in Tanganyika. Isolated and surrounded by relatively hostile powers, the KPPF sought outside support. They attempted to court the Soviet Union, but the Khrushchev government, relatively uninterested by African affairs and preoccupied with events elsewhere, refused to support the KPPF. However, the KPPF found a more sympathetic ear with the Mao regime in China. Chinese support in arms and money entered Kirinyaga-Kenyaland via the dirt roads along the border with Tanganyika, a state which hosted exiled opposition leaders Stanley Mathenge, Waruhiu Itote and Musa Mwariama of the KNU. This precarious strategic situation fueled paranoia in the ruling KPPF junta, which boiled over as a result of the political aftermath of the 1965 famine, where thousands starved to death as a result of poorly-handled land reform. In a number of areas, local farmers and pastoralists violently resisted the requisition of their yield, resulting in the burning down of a number of villages by government militia. As his government became increasingly shaky, President Bildad Kaggia became increasingly reliant on Interior Minister Dedan Kimathi to maintain rule by force. Claiming that the opposition were "imperialist stooges" and referring to the hopelessly outnumbered armed peasants as "askaris", Kaggia introduced martial law. In March 1966, seeking to take advantage of turmoil in Kirinyaga-Kenyaland, and seeking to prove the effectiveness of their new army, which had expelled British officers, Nyerere ordered an incursion into Kirinyaga-Kenyaland in order to topple the KPPF and put the KNU troika into power.

Marching over the border, supported by a small number of armoured cars, the KNU militia with support from the Tanganyikan People's Defence Force were engaged by Kirinyagan troops which held the line in the Namanga Hills. Kimathi immediately travelled to the region to take total command. Rather than attempting to destroy the enemy forces, Kimathi successfully drew the attackers into the forested hills, where they were unable to take advantage of the Tanganyikans' firepower superiority due to the broken terrain and poor lines of sight. Armoured cars were incapable of moving within the elevated cloud forest, constricted to the poor roads between the two nations, where they were susceptible to ambush by Maasai warriors armed with RPGs. Reinforcements by Gĩkũyũ troops from central Kirinyaga put huge pressure on the poorly-trained invading forces, which collapsed and fled across the border back into Tanganyika. Kirinyaga troops engaged in a number of cross-border raids, which were notorious for the scale of sexual violence. These attacks halted when Chinese diplomats informed the KPPF junta that any attempt to invade Tanganyika would result in the cession of support from the PRC. A ceasefire ensued, with the Zanzibari revolutionary government brokering peace between the warring states. One major result of the war was that Kirinyaga was forced to turn to the Swahili Coast for trade with the outside world. Despite distaste for Kirinyaga and its government (intensified by Mau Mau attacks on Mijikenda villages during the independence struggle), Kirinyaga was allowed to trade out of Swahili ports in exchange for major dues. This arrangement would continue, with Kirinyaga becoming increasingly dependent on petroleum products imported from the Arab world via Swahili ports. In 1969, after political maneuvering, Dedan Kimathi took advantage of his status as victor of the war against Tanganyika to overthrow Kaggia in a coup, having forged documents falsely claiming that he was taking money from the British. Throughout the 1970s, Kirinyaga continued to stagnate, with Kimathi ruling increasingly despotically, taking a number of concubines and embezzling money through Swiss bank accounts. Opposition was dealt with viciously, and aside from state-dominated trade with commercial cartels in the Swahili Coast, the state pursued autarky. Unlike other socialist states, which at least pushed education and full-employment, the Kirinyagan state kept people in agrarian occupations. As a result, they had one of the worst literacy rates in Africa. Only government bureaucrats and military families were given a state-sponsored education. Starvation was common, as the increasingly militarised state was funded by the requisitioning of grain.

Dedan Kimathi, victor of the Kirinyaga-Tanganyika War and later President of Kirinyaga