You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Stars and Sickles - An Alternative Cold War

- Thread starter Hrvatskiwi

- Start date

-

- Tags

- cold war

Threadmarks

View all 122 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 98: The Conqueror? - Uganda (Until 1980) (Part 2) Chapter 99: Slaying the Beast - Uganda (Until 1980) (Part 3) Chapter 100 [SPECIAL] - Ad Astra - Aerospace Competition Between the Superpowers (Until 1980) (Part 1) Chapter 101 [SPECIAL] - Magnificent Desolation - Aerospace Competition Between the Superpowers (Until 1980) (Part 2) Chapter 102: Jadi Pandu Ibuku - Nusantara (Until 1980) Chapter 103: Furtive Seas - South Maluku and West Papua (Until 1980) Chapter 104: Kings and Kingmakers - Post-Independence North Kalimantan (Until 1980) Chapter 105: Maka-Diyos, Maka-Tao, Makakalikasan, at Makabansa - The Philippines (Until 1980)I can believe you're finally back!! Maybe now we can have a sucessful communist revolution in Brazil lol

Chapter 80: No Fist is Big Enough to Hide the Sky - Portugal's Colonial Wars and their Consequences (Part 1)

Since 1932, southern Europe's Atlantic outpost of Portugal had been governed by the Novo Estado regime of António de Oliviera Salazar. By 1960, this was the oldest right-wing authoritarian government in Europe. The Salazar government had never seriously considered aligning with the Axis powers, both due to economic dependency on Britain and major ideological differences between the traditionalist Catholic and assimilationist views of the Salazar regime and the race-obsessed Nazi government in Germany. After the Second World War, the Estado Novo was embraced with open arms by NATO despite some misgivings about its anti-democratic governance due to its staunch anti-communism. From the beginning of the 1950s, Salazar began to promote the national character of Portugal as pluricontinentalism, that is, the idea that Portugal as a nation was a product of overseas expansion during the Age of Exploration, and as such that the overseas possessions of Portugal were just as much a legitimate part of the nation as the metropole. The legacy of the once-lucrative spice trade that took the caravels of Portugal around the Cape of Good Hope and all the way to the Far East and back remained in the form of a handful of colonial possessions: Goa had been annexed by India, but Macao, Mozambique, Angola, East Timor, Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde remained under Lisbon's authority. By the 1960s, however, this grip was tenuous. All of these territories began to see political organisation amongst their small educated indigenous class and Salazar had come under intensifying diplomatic pressure from Washington to follow the same decolonisation process in their sub-Saharan African colonies as the British and French had done. A failed coup attempt, the Botelho Moniz coup, was mounted in 1961 with the tacit support of Washington. Consolidating power after this failed putsch, Salazar ramped up the commitment to retaining Portuguese control in the far-flung colonies.

The struggle for independence in Portugal's West African holdings of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde was headed by the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde, PAIGC), established in 1956. Initially seeking self-determination through peaceful dialogue with the Salazar regime, it rapidly became apparent that Lisbon would not part ways with the territory without violence. The Pidjiguiti Massacre of 1959 was a major turning point for the Bissau-Guinean nationalists; fifty protesting dockworkers were killed by Portuguese troops. This event outraged the indigenous population of the colony and provided a great deal of propaganda value for the PAIGC. Preparing for armed resistance, PAIGC started to establish camps across the border in Guinea-Conakry. In March 1962, PAIGC operatives mounted an abortive attack on the Cape Verdean capital of Praia. Portuguese control of the seaways meant that there would be no further attacks on Cape Verde by PAIGC-aligned militants, but they would have a significant clandestine presence on the island. Many of PAIGC's leaders, including Amílcar and Luís Cabral, were Cape Verdean creoles and maintained strong links with the community. As such, there was a fairly extensive network of informants and saboteurs operating on the archipelago on their behalf.

In early 1963, hostilities on the Guinea-Bissau mainland commenced. PAIGC militants began to ambush Portuguese patrols. Whilst being poorly-equipped, the raids gradually allowed them to begin accumulating arms and ammunition. The Portuguese troops were taken somewhat by surprise. They had prepared for cross-border raids originating from the camps in Guinea-Conakry, but the initial attacks instead came from within the territory. Amílcar Cabral, the leader of PAIGC, had ensured that the national liberation forces had ingratiated themselves with the rural peasantry. A trained agronomist who had encountered anti-colonial ideology whilst at university in Lisbon, Cabral ensured that his troops were trained in modern agricultural techniques so that they could give advice to rural farmers, garnering goodwill. They were also ordered that when not engaging in combat operations, to assist with labour on the local plantations, thus earning their food, rather than requisitioning produce by force, an action which would almost certainly turn the population against them. As the war went on, Cabral would also orchestrate a programme of roving markets and hospitals, ensuring that the rural peasantry would have access to goods and medical services that would have been prohibitively expensive if purchased from the colonial-run general stores. PAIGC initially avoided engagement with any Portuguese force beyond platoon level, but nevertheless had consolidated its position in the southern littoral and gained a modest foothold in the north. Initially the independence PAIGC cells were organised around tribal relationships, and as such engaged in occasional abuse when interacting with peasants of neighbouring groups. This horrifies the PAIGC leadership, which recognised how this jeopardised their entire campaign. In 1964, PAIGC held the Cassaca Congress, which restructured the PAIGC cells, bringing them under a central command. The armed rebels were organised into the Revolutionary Armed Forces of the People (Forças Armadas Revolucionárias do Povo, FARP). This change immediately improved discipline amongst the insurgents. All FARP units would be under joint command from both a military commander and a political commissar in order to combat what the PAIGC referred to as "commandism". This made FARP relatively unique amongst national liberation movements in the Third World, where it was typical that the brutalising nature of asymmetrical warfare would precipitate a descent into brigandage.

In 1964 FARP opened a new front in the north of the country as they consolidated further control of the south. After occupying the estuary island of Como in the south, FARP came under attack from a combined armed offensive from the Portuguese, Operação Tridente, involving all three branches of the Portuguese military. Poor coordination between the branches resulted in slow progress for the Portuguese counteroffensive. A particularly embarassing incident during this battle was the bombing of Portuguese troops by their own planes, which had misidentified them. Some reports suggest that barracks brawls occurred between soldiers and airmen in the aftermath, although these reports cannot be verified. After the recapture of Como, Portuguese forces redeployed to support the besieged garrisons on the peninsulas of Cantanhez and Quitafine. In 1965 the war had spread to the country's east; FARP would have less control over this area than the rest of the country due to the close relationship between the colonial government and the local Fulbe chiefs. Fulbe were also overrepresented in the Portuguese army. In the same year, FARP took action against the only other armed group of any note on the territory, the Struggle Front for the National Independence of Guinea (Frente de Luta pela Independência Nacional da Guiné, FLING). Unlike PAIGC, FLING solely sought independence for Guinea-Bissau, disregarding the Cape Verdean self-determination movement. It maintained close links with the national trade union federation and was largely comprised of Manjak people. Their funding largely originated from the Manjak diaspora in Senegal, Gambia and France. Having rebuffed attempts by the Organisation of African Unity to join a united front with PAIGC, FLING came under attack from PAIGC and was largely crushed, their leaders fleeing to other West African nations such as Cote d'Ivoire. Amílcar Cabral, who had a past as an asset of the Czechoslovak State Security Bureau (StB) also managed to acquire shipments of relatively modern weaponry form the Soviet Union, China, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia.

By 1968, when António de Spínola arrived in Portuguese Guinea from Angola, he immediately began to implement a more modern approach to counter-insurgency. At the time of his arrival, PAIGC had by then taken control of two-thirds of the territory. Spínola commenced a construction and infrastrucure-building campaign in order to improve economic development in the hopes that this would begin to improve the Portuguese reputation in the eyes of native peoples. Spínola did, however, also oversee the introduction of new weapons to the conflict; Portuguese bombers started to drop napalm on suspected FARP positions; and the dense forests were attacked with chemical defoliants to limit ambush opportunities for the rebels. Spínola also began the process of "Africanisation" of the Portuguese fighting force in Guinea. Two elite forces comprised of indigenous Africans was established: the Special African Marines and the African Commandoes. The Special African Marines were tasked with riverine operations in order to harass and interdict FARP activity. The African Commandoes were used in 'search-and-destroy' missions and deep-insertion missions. The commandoes were notable for their effectiveness, but also their ruthlessness.

Improved battlefield performance bolstered operational confidence; Portuguese troops started engaging in bolder actions, including air cavalry infiltration raids and most notably Operation Green Sea: an amphibious raid on the capital of neighbouring Guinea. Operation Green Sea had a couple of objectives, the foremost of which was to free Portuguese POWs who were being held in Conakry. The secondary objectives were, if given the opportunity, to capture Amílcar Cabral and/or Sékou Touré. On the night of 22 November 1970, the Portuguese soldiers landed from several unmarked ships and quickly fanned out to seize several points throughout the capital, facing only ineffectual resistance from local militia. The attackers were unable to locate Sékou Touré, who was hiding in the Presidential Palace, or Amílcar Cabral, who was in Eastern Europe at the time. Half of the raiders then withdrew, a small force of around 200 staying around for some hours afterwards, apparently expecting an uprising by locals against the Sekou-Toure government. When it became clear that such an uprising wasn't coming, this force also withdrew. Almost immediately after Operation Green Sea, Sékou Touré's government started to purge suspected defectors or sympathisers with the opposition, becoming increasingly concerned about the possibility of a coup with Portuguese backing. The Portuguese raid was condemned by the United Nations and the Soviets responded by increasingly the provision of advanced armaments to the FARP forces and to the Guinean military, including four Ilyushin Il-4 bombers which were provided to the Bissau-Guinean separatists. Additionally, a permanent Soviet naval force, the West Africa Squadron, was stationed in Conakry to ensure that Portuguese operations in Guinea-Bissau didn't spill over to neighbouring states.

Between August and November 1972, PAIGC held elections in the "liberated zones" to establish regional councils, whose representatives would then elect a National Assembly. Despite only PAIGC candidates being eligible for election, this process was still the most democratic to occur in Guinea-Bissau's history. Previous elections held by the Portuguese had limited suffrage to a mere few thousand who met tax and literacy requirements. By contrast, the 1972 elections saw 78,000 participants. On 20th January 1973, Amílcar Cabral survived an assassination attempt by FARP naval commander Inocêncio Kani (with the assistance of the PIDE, the Portuguese secret police) who intended to start a coup [182]. Kano would be executed along with ten other conspirators. On 24th September 1973, PAIGC unilaterally declared the independence of Guinea-Bissau, which was recognised by an overwhelming majority of the UN General Assembly. Amílcar Cabral would be the first President of the infant nation.

---

[182] IOTL, Amílcar Cabral was killed and his brother Luís would become President of the new republic.

The struggle for independence in Portugal's West African holdings of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde was headed by the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde, PAIGC), established in 1956. Initially seeking self-determination through peaceful dialogue with the Salazar regime, it rapidly became apparent that Lisbon would not part ways with the territory without violence. The Pidjiguiti Massacre of 1959 was a major turning point for the Bissau-Guinean nationalists; fifty protesting dockworkers were killed by Portuguese troops. This event outraged the indigenous population of the colony and provided a great deal of propaganda value for the PAIGC. Preparing for armed resistance, PAIGC started to establish camps across the border in Guinea-Conakry. In March 1962, PAIGC operatives mounted an abortive attack on the Cape Verdean capital of Praia. Portuguese control of the seaways meant that there would be no further attacks on Cape Verde by PAIGC-aligned militants, but they would have a significant clandestine presence on the island. Many of PAIGC's leaders, including Amílcar and Luís Cabral, were Cape Verdean creoles and maintained strong links with the community. As such, there was a fairly extensive network of informants and saboteurs operating on the archipelago on their behalf.

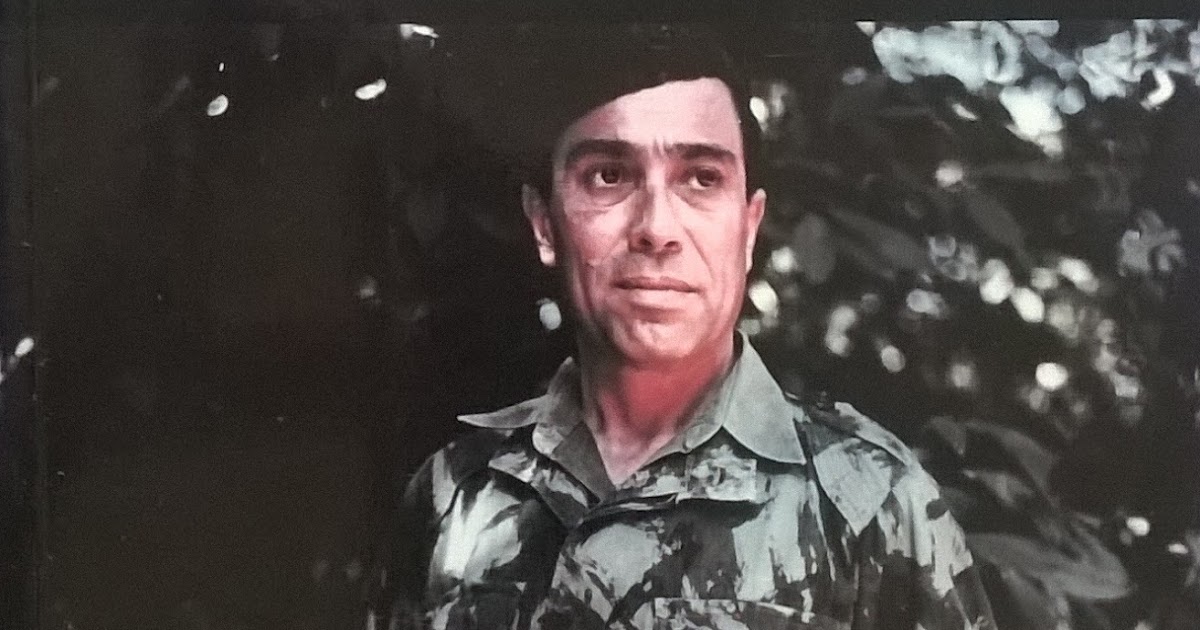

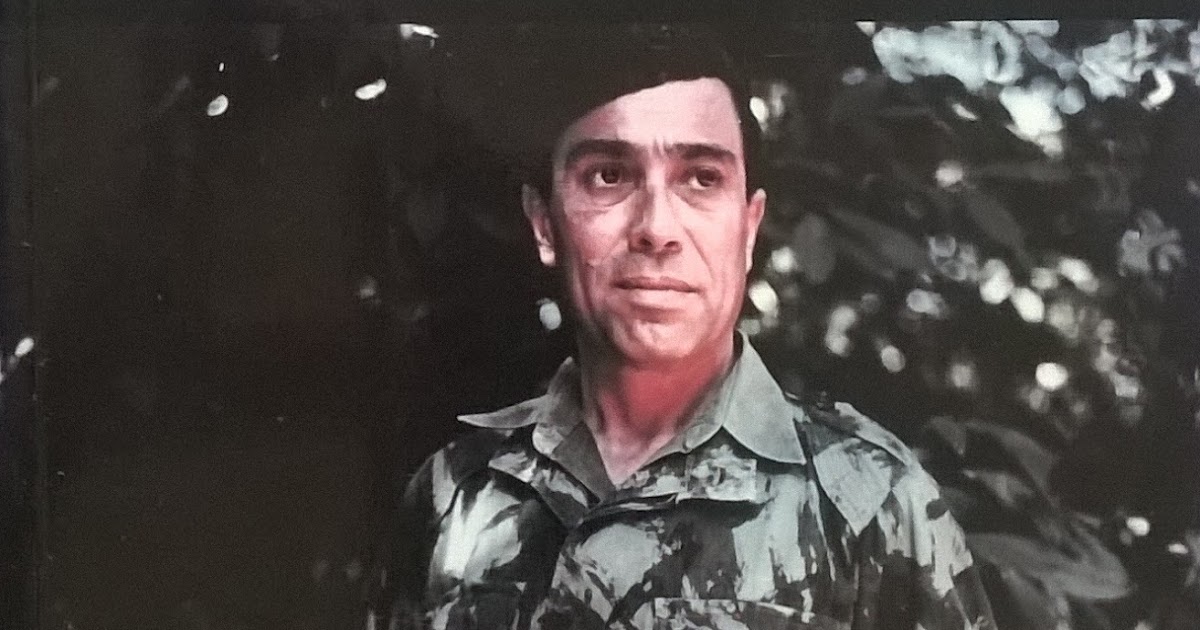

Amílcar Cabral, leader of the PAIGC

In early 1963, hostilities on the Guinea-Bissau mainland commenced. PAIGC militants began to ambush Portuguese patrols. Whilst being poorly-equipped, the raids gradually allowed them to begin accumulating arms and ammunition. The Portuguese troops were taken somewhat by surprise. They had prepared for cross-border raids originating from the camps in Guinea-Conakry, but the initial attacks instead came from within the territory. Amílcar Cabral, the leader of PAIGC, had ensured that the national liberation forces had ingratiated themselves with the rural peasantry. A trained agronomist who had encountered anti-colonial ideology whilst at university in Lisbon, Cabral ensured that his troops were trained in modern agricultural techniques so that they could give advice to rural farmers, garnering goodwill. They were also ordered that when not engaging in combat operations, to assist with labour on the local plantations, thus earning their food, rather than requisitioning produce by force, an action which would almost certainly turn the population against them. As the war went on, Cabral would also orchestrate a programme of roving markets and hospitals, ensuring that the rural peasantry would have access to goods and medical services that would have been prohibitively expensive if purchased from the colonial-run general stores. PAIGC initially avoided engagement with any Portuguese force beyond platoon level, but nevertheless had consolidated its position in the southern littoral and gained a modest foothold in the north. Initially the independence PAIGC cells were organised around tribal relationships, and as such engaged in occasional abuse when interacting with peasants of neighbouring groups. This horrifies the PAIGC leadership, which recognised how this jeopardised their entire campaign. In 1964, PAIGC held the Cassaca Congress, which restructured the PAIGC cells, bringing them under a central command. The armed rebels were organised into the Revolutionary Armed Forces of the People (Forças Armadas Revolucionárias do Povo, FARP). This change immediately improved discipline amongst the insurgents. All FARP units would be under joint command from both a military commander and a political commissar in order to combat what the PAIGC referred to as "commandism". This made FARP relatively unique amongst national liberation movements in the Third World, where it was typical that the brutalising nature of asymmetrical warfare would precipitate a descent into brigandage.

In 1964 FARP opened a new front in the north of the country as they consolidated further control of the south. After occupying the estuary island of Como in the south, FARP came under attack from a combined armed offensive from the Portuguese, Operação Tridente, involving all three branches of the Portuguese military. Poor coordination between the branches resulted in slow progress for the Portuguese counteroffensive. A particularly embarassing incident during this battle was the bombing of Portuguese troops by their own planes, which had misidentified them. Some reports suggest that barracks brawls occurred between soldiers and airmen in the aftermath, although these reports cannot be verified. After the recapture of Como, Portuguese forces redeployed to support the besieged garrisons on the peninsulas of Cantanhez and Quitafine. In 1965 the war had spread to the country's east; FARP would have less control over this area than the rest of the country due to the close relationship between the colonial government and the local Fulbe chiefs. Fulbe were also overrepresented in the Portuguese army. In the same year, FARP took action against the only other armed group of any note on the territory, the Struggle Front for the National Independence of Guinea (Frente de Luta pela Independência Nacional da Guiné, FLING). Unlike PAIGC, FLING solely sought independence for Guinea-Bissau, disregarding the Cape Verdean self-determination movement. It maintained close links with the national trade union federation and was largely comprised of Manjak people. Their funding largely originated from the Manjak diaspora in Senegal, Gambia and France. Having rebuffed attempts by the Organisation of African Unity to join a united front with PAIGC, FLING came under attack from PAIGC and was largely crushed, their leaders fleeing to other West African nations such as Cote d'Ivoire. Amílcar Cabral, who had a past as an asset of the Czechoslovak State Security Bureau (StB) also managed to acquire shipments of relatively modern weaponry form the Soviet Union, China, Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia.

FARP guerrillas pose for a photo, Guinea-Bissau (note the Soviet weapons)

By 1968, when António de Spínola arrived in Portuguese Guinea from Angola, he immediately began to implement a more modern approach to counter-insurgency. At the time of his arrival, PAIGC had by then taken control of two-thirds of the territory. Spínola commenced a construction and infrastrucure-building campaign in order to improve economic development in the hopes that this would begin to improve the Portuguese reputation in the eyes of native peoples. Spínola did, however, also oversee the introduction of new weapons to the conflict; Portuguese bombers started to drop napalm on suspected FARP positions; and the dense forests were attacked with chemical defoliants to limit ambush opportunities for the rebels. Spínola also began the process of "Africanisation" of the Portuguese fighting force in Guinea. Two elite forces comprised of indigenous Africans was established: the Special African Marines and the African Commandoes. The Special African Marines were tasked with riverine operations in order to harass and interdict FARP activity. The African Commandoes were used in 'search-and-destroy' missions and deep-insertion missions. The commandoes were notable for their effectiveness, but also their ruthlessness.

Improved battlefield performance bolstered operational confidence; Portuguese troops started engaging in bolder actions, including air cavalry infiltration raids and most notably Operation Green Sea: an amphibious raid on the capital of neighbouring Guinea. Operation Green Sea had a couple of objectives, the foremost of which was to free Portuguese POWs who were being held in Conakry. The secondary objectives were, if given the opportunity, to capture Amílcar Cabral and/or Sékou Touré. On the night of 22 November 1970, the Portuguese soldiers landed from several unmarked ships and quickly fanned out to seize several points throughout the capital, facing only ineffectual resistance from local militia. The attackers were unable to locate Sékou Touré, who was hiding in the Presidential Palace, or Amílcar Cabral, who was in Eastern Europe at the time. Half of the raiders then withdrew, a small force of around 200 staying around for some hours afterwards, apparently expecting an uprising by locals against the Sekou-Toure government. When it became clear that such an uprising wasn't coming, this force also withdrew. Almost immediately after Operation Green Sea, Sékou Touré's government started to purge suspected defectors or sympathisers with the opposition, becoming increasingly concerned about the possibility of a coup with Portuguese backing. The Portuguese raid was condemned by the United Nations and the Soviets responded by increasingly the provision of advanced armaments to the FARP forces and to the Guinean military, including four Ilyushin Il-4 bombers which were provided to the Bissau-Guinean separatists. Additionally, a permanent Soviet naval force, the West Africa Squadron, was stationed in Conakry to ensure that Portuguese operations in Guinea-Bissau didn't spill over to neighbouring states.

Portuguese troops on parade through a colonist settlement, Guinea-Bissau, 1962

Between August and November 1972, PAIGC held elections in the "liberated zones" to establish regional councils, whose representatives would then elect a National Assembly. Despite only PAIGC candidates being eligible for election, this process was still the most democratic to occur in Guinea-Bissau's history. Previous elections held by the Portuguese had limited suffrage to a mere few thousand who met tax and literacy requirements. By contrast, the 1972 elections saw 78,000 participants. On 20th January 1973, Amílcar Cabral survived an assassination attempt by FARP naval commander Inocêncio Kani (with the assistance of the PIDE, the Portuguese secret police) who intended to start a coup [182]. Kano would be executed along with ten other conspirators. On 24th September 1973, PAIGC unilaterally declared the independence of Guinea-Bissau, which was recognised by an overwhelming majority of the UN General Assembly. Amílcar Cabral would be the first President of the infant nation.

---

[182] IOTL, Amílcar Cabral was killed and his brother Luís would become President of the new republic.

Amazing chapter, hoping the rest of Portuguese Africa can free itself from colonial rule and that will serve as inspiration for the ANC in South Africa to keep resisting. Super glad seeing this amazing TL back as well!

Thanks Kurt! Will definitely be posting more regularly, now that my work situation has changed a bit.Amazing chapter, hoping the rest of Portuguese Africa can free itself from colonial rule and that will serve as inspiration for the ANC in South Africa to keep resisting. Super glad seeing this amazing TL back as well!

Always great to have you along for the ride!

Chapter 81: The One Who Throws the Stone Forgets; The One Who is Hit Remembers Forever - Portugal's Colonial Wars and their Consequences (Part 2)

Unlike the conflict in Guinea-Bissau, Angola's war of independence was characterised by the factionalism of the resistance movements. The three primary parties involved, the FNLA, MPLA and UNITA, were notable not only for their willingness to fight each other rather than just the colonial occupiers, but also their tendency to shift their patronage constantly, limiting their ability to maintain a strong relationship with overseas backers. Furthermore, the discovery of large off-shore oil reserves partway through the war ensured that the meddling of foreign powers was everpresent.

Recognising a higher degree of unrest amongst the native traditional rulers of Angola, in 1951 the Portuguese government changed the status of the territory, from a formal "colony" of Lisbon into a "overseas province". Despite this shift, governance of Angola remained under the control of a white-operated government bureaucracy, with only local input required from traditional native leaders. This was seen as a particular affront in the northwest of Angola, in the territories that had once made up the Kingdom of Kongo. In 1954, the União dos Povos do Norte de Angola (Union of Peoples of Northern Angola, UPA) was established under the leadership of Holden Roberto, a descendant of Bakongo royalty. Despite the name, the UPA was almost entirely comprised of Bakongo people, seeking to resurrect their independence from Portugal, with little consideration for the other Angolan peoples. Two years later, the Angolan Communist Party and the Party of the United Struggle for Africans in Angola merged to form the Movimento Popular de Liberação de Angola (People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola, MPLA). The MPLA drew its ranks primarily from Luanda's urban intelligentsia and the Ambundu people who lived on territories centred around Luanda and the Cuanza river. These Ambundu were the historical heirs to the legacy of the Ndongo Kingdom, but the MPLA promoted a message of unity between the various peoples of Angola, including (at least rhetorically) a willingness to accept Angolans of European descent into their organisation.

On January 3, 1961, the tensions that were building up in Angola came to a head. Agricultural workers employed by Belgian-Portuguese cotton plantation operation Cotonang staged a protest in Baixa de Cassanje demanding an improvement in working conditions. The demonstrators would go as far as beating Portuguese traders that were onsite. Spontaneous shows of support broke out in nearby settlements, and was suppressed by a Portuguese terror-bombing campaign which targeted twenty surrounding villages. The MPLA claimed that the death toll was 10,000, and while this is most likely an exaggeration, historical estimates range between 400 and 7,000 dead native Angolans. A couple of days later, the Portuguese liner Santa Maria was seized by operatives of the Iberian Revolutionary Liberation Directorate (DRIL) operating under the command of Henrique Galvão, a military officer and general secretary of DRIL's Portuguese branch. Intending to establish an opposition Portuguese government in Angola, he was instead forced to redirect to Brazil, liberating the crews and passengers in exchange for political asylum. Between the fourth and tenth of January, a number of armed incidents took place in Luanda. Whilst the exact details are unclear, with several parties having given contradictory accounts, there were a number of attacks on police by black militants armed with machetes, followed by a police response in black-majority neighbourhoods in the city. Some claim that the police response was also accompanied by lynchmobs of white settlers, whereas others claim this to be a fabrication intended to strain relations between the communities. Responsibility for the initial attacks was claimed by the MPLA, although the Portuguese secret police claimed that a local nationalist priest was behind the incident.

On March 15, the UPA staged a major uprising in the Bakongo territories; farmers and coffee plantation workers took up arms and what ensued was a slaughter. A thousand white settlers were killed, along with thousands more native workers, mostly ethnic Ovimbundu people from the central highlands, who were in the north as contract labourers. Arson attacks were carried out on police stations, plantations, ferries and many other targets. Journalists published images of raped and mutilated white settlers in newspapers in the metropole and throughout the rest of the colony, manufacturing consent for a heavy-handed response from the military. Later testimony also claimed that some UPA forces engaged in cannibalism of killed Portuguese soldiers. Whilst there were plenty instances of farms and smaller hamlets being completely overrun, many of the Portuguese settlers in the area retreated into regional hubs and entrenched themselves, forming militias in order to rebuff the disorganised assaults from the untrained insurrectionists. These militias would afterwards be organised into the Organização Provincial de Voluntários de Defesa Civil (OPVDC), a paramilitary force tasked with settlement defense and auxiliary support for the Portuguese regular military. This caught Roberto and the rest of the UPA leadership by surprise, as they expected the white settler population of the region to flee in panic. It is worth noting that this revolt wasn't simply an anti-colonial rebellion; it was an attempt by the UPA leadership to reassert political and economic authority over the northern regions. Attacking Ovimbundu contract workers with the same savagery as white colonists, the UPA insurrectionists sought to create conditions of Bakongo supremacy in the former Kongo territories.

On July 10, after having reoccupied some of the smaller northern towns, the Portuguese military commenced Operação Viriato to conquer the town of Nambuangongo, which had become the UPA headquarters. Converging on the town along three axes, the Portuguese occupied the town a month after the commencement of the operation. The Portuguese also captured the village of Quipedro to interdict the UPA's line of retreat from Nambuangongo. The attack on Quipedro was achieved through an airborne assault which took the revolters by suprise and resulted in the capture of the village without effective resistance. Attempting to provide a carrot to go along with the stick, on August 6 the Novo Estado adopted the Statute of the Portuguese Indigenous of the Provinces of Guinea, Angola & Mozambique, giving all indigenes equal citizenship rights and obligations as ethnic Portuguese. On 16th September, the UPA's last base in northern Angola, Pedra Verde, was captured by Portuguese troops in Operação Esmeralda. The UPA had no choice but to flee over the border to Congo, the Portuguese having killed 20,000 in this suppression campaign. Despite some misgivings about the UPA's refusal to adopt pan-Africanist ideology, Lumumba's government nevertheless allowed the UPA to establish bases on their side of the border in order to harass the Portuguese colonialists. The 9th October also saw a small incident that would have major consequences for the future of Angola: a UPA patrol took 21 MPLA personnel prisoner and executed them, precluding any chance of cooperation between the two resistance groups. After fleeing to Congo, the UPA merged with the Democratic Party of Angola and renamed itself the Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola (FNLA).

February 1962 saw the establishment of the Angolan Revolutionary Government in Exile (GRAE) in Congo, with Holden Roberto as its President and Jonas Savimbi as Foreign Minister. Later that same year, an MPLA congress replaced General-Secretary Viriato da Cruz with Agostinho Neto. Da Cruz and Neto had clashed on several occasions, particularly on the subject of the racial composition of the party. Da Cruz, despite being of mixed ancestry himself, wanted to reserve a number of party seats for black African members. Whilst there was some diversity amongst MPLA ranks, the leadership, being drawn from the Luanda intelligentsia, was predominantly mestiço. In the enclave of Cabinda in the north, 1963 saw the merging of three nationalist groups into the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda (FLEC) which began low-level engagements with Portuguese security forces, mostly police. Their cause was bolstered diplomatically by the declaration of Cabinda as an independent state by the Organisation of African Unity. Nevertheless, they would pose very little threat to the Portuguese military. Dialogue did however, commence between the government of Congo and the FLEC.

In 1964, frustrated by Holden Roberto's unwillingness to spread the guerrilla operations of the FNLA outside of the Bakongo territories, his insistence on refusing support from the Soviet Union and China, and the lack of a political programme, Jonas Savimbi left the FNLA and relocated to China with some supporters. Meanwhile, the MPLA started slowly building up its strength, receiving armaments from the Soviet Union and the German Democratic Republic. Relative to the more unified and effective FARP in Guinea-Bissau, the MPLA received only older surplus weaponry, particularly from the GDR. Whereas the image of the AK-47-toting militant may have been associated with the various national liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s, it was far more common in Angola to see MPLA insurgents armed with old Mauser bolt-action rifles. In May of 1966, Daniel Chipenda of the MPLA established a new area of operations, the Eastern Front, almost doubling the MPLA's reach. Jonas Savimbi, returning from China, establishing the União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola, UNITA) in a conference at Moxico province in the southeast on March 13. UNITA would commence armed operations on Christmas Day, derailing trains passing along the Benguela railway at Teixiera de Sousa, on the border with Rhodesia-Nyasaland. Immediately UNITA had an impact, with their forces being much better-led and trained than either FNLA or MPLA guerrillas. UNITA operations along this railway would especially frustrate the leadership of the neighbouring white-ruled Central African Federation, which relied on the Benguela railway to bring its copper exports to a port where it could reach foreign markets. The following year, UNITA would be successful in two more major derailings along this line, although increasing pressure from the Portuguese military in the region caused Savimbi to himself relocate to Cairo. Savimbi also established some contacts with Portuguese intelligence, where he would pass on information about the location of MPLA bases in order to undermine his pro-Soviet rivals.

May of 1968 saw FNLA fighters cross for the first time into Eastern Angola. By this time, it was clear that Eastern Angola would become an important battlefield, allowing any group which controlled this region to monopolise the control of blood diamonds in this area, as well as to interfere with the ability of their rival rebel groups to get support from their neighbours such as Congo and Rhodesia-Nyasaland. As may be expected by an organisation that was so strongly tied to one particular ethnic group, the FNLA operations in Eastern Angola were typically brutal, aimed at control of diamond production and with little care for the wellbeing of the local populations. In October, the Portuguese mounted Operação Vitória to root out MPLA bases in the east. Portuguese forces also managed to capture important documents that revealed the position of various other MPLA troops positions. For their part, the MPLA did also discreetly pass on the location of FNLA patrols to Portuguese troops. Despite the continued operation of the rebel forces, by this point in the war the momentum was clearly in the favour of the Portuguese. All separatist forces were secretly sending intel on their rivals to the Portuguese, and the colonial forces were also increasingly utilising the most modern counterinsurgency techniques. Whilst elements of the Portuguese command still distrusted African troops, there was an increase in recruitment of them, as other notable figures in the army such as Spínola and Francisco da Costa Gomes promoted their use, claiming that they're cheaper than European troops, more accustomed to the local climate and terrain and better able to develop relationships with local communities. The PIDE even established its own elite paramilitary force, the Flechas (Portuguese for Arrows) comprised predominantly of Khoisan bushmen. Specialising in covert operations, close quarters combat, desert warfare, jungle warfare, and virtually all other skillsets that would later come to be known as "black operations", these forces didn't operate under the command of the army but where entirely an instrument of the Portuguese secret police. They were particularly feared due to their brutality and their ability to sudden strike with no warning. Some of the more superstitous rebels even believed them to have supernatural powers garnered from black magic, a reputation that the PIDE didn't try to dispel. The regular military established Battle Group Sirocco, a highly mobile task force assisted by a dedicated air cavalry arm that would engage in rapid response operations throughout Eastern Angola. Whilst at the onset of the colonial war, the Portuguese forces had somewhat struggled to find their footing due to their initial composition as a component of overall NATO, and later LDO command, by the late 1960s they were well-versed in irregular combat in difficult terrain. In response, the rebel forces were forced to begin former larger squadrons in order to have any combat effectiveness at all. The MPLA began operating squadrons of 100 to 145 militants rather than the old platoon-sized cells. Armed with 60mm and 81mm mortars provided by the USSR, they were limited to attacks on small outposts and patrols, but were unable to make any real notable headway. To make matters worse for the MPLA, in 1972 South African Defense Force (SADF) units began engaging them in Moxico province with Portuguese consent. Operating through Rhodesia-Nyasaland, the SADF forces were there to take revenge for MPLA support for the South-West African People's Organisation (SWAPO) which operated in the territory of South-West Africa, which South Africa administered initially under trusteeship but had de facto annexed despite condemnation from the United Nations. The SADF campaign forced the MPLA out of Moxico province. The combined Portuguese and South African offensives in the east effectively pushed the MPLA out of that territory. This turn of events precipitated infighting amongst the leadership of the MPLA. Neto and 800 of his fighters retreated into Congo, whilst Chipenda began secret negotiations with the Soviets to shift their support away from Neto.

On 17th March, 1,000 FNLA fighters mutiny at camps in Kinkuzu within Congolese territory, but were suppressed by Congolese troops on behalf of FNLA leadership. In 1973, Daniel Chipenda left the MPLA, and forming a rival group, the Revolta do Leste (Eastern Revolt) with 1500 followers and covert Soviet and South African support (motivated by the desire to further undermine the MPLA). Despite Soviet support, he was privately wary of Soviet influence, and strongly opposed to the mestiço leadership of the MPLA. Later that year, Neto was invited to Moscow and told that Chipenda planned to assassinate him. These events have raised some speculation that Soviet support for the Eastern Revolt was part of a KGB operation seeking to maintain MPLA integrity by passing along information about rivals to Neto. China also shifted aid away from MPLA, sponsoring UNITA but also the FNLA, presumably in order to undermine the pro-Soviet MPLA. 1973 saw another split in MPLA, with founder Mário Pinto de Andrade clashing with Neto and establishing their own group, the Revolta Activa. Neto managed to reassert his authority soon thereafter, with Pinto de Andrade fleeing to Guinea-Bissau. The Revolta do Leste merged with FNLA. The internecine fighting amongst the rebel groups would have almost certainly lead to eventual victory for the Portuguese colonial forces, but events in the metropole changed the destiny of Angola and left the nation's future in the hands of these warring factions.

Disparities between the settler population and indigenous Africans was even more severe in Mozambique. Under the Estado Novo regime, indigenous farmer were compelled to produce cash crops such as cotton for export, forcing them in many instances to forage or to buy food at raised prices from ethnic Portuguese farmers, whilst selling their cash crops at reduced rates, despite living on arable land that would otherwise be able to sustain their nutritional needs without issue. Over a quarter of a million native Mozambicans also worked in Rhodesia-Nyasaland and South Africa (in the latter, they comprised over 3/10s of underground miners) and were heavily taxed by the Mozambique colonial administration for their remittances. In 1950, out of a total indigenous Mozambican population of over 5 and a half million, a mere 4,000 or so natives possessed voting rights. Rates of ethnic intermixing were also the lowest in Mozambique of all the Portuguese colonies, by 1960 only numbering around 31,000. This number also underscores the vast degree of segregation between native and settler communities, which resembled the conditions in neighbouring South Africa more so than in Angola or Cabo Verde. The Liberation Front of Mozambique (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique, FRELIMO) was established in 1962 in Zanzibar [183] under the leadership of Eduardo Mondlane, a historian and sociologist who had briefly worked as a professor at New York's Syracuse University. FRELIMO had been created as a union of a number of smaller, disparate independence movements which had sprouted up, inspired by the pan-African liberation movements and the newfound independence of several states which had once been under British, French and Belgian rule. FRELIMO was initially completely reliant on support from friendly regimes, as the Estado Novo's ruthless intelligence apparatus had forced the Mozambique independence movement into exile. FRELIMO guerrillas were allowed to train (with Chinese assistance) and operate from bases in southern Tangyanika. With only around 7,000 fighters, a conventional victory against the Portuguese was a hopeless proposition; but a protracted guerrilla war had potential to force Lisbon to the negotiating table.

1964 saw the first FRELIMO attacks in Mozambique, negotiations with the Portuguese having proven fruitless. FRELIMO guerrillas, with assistance from the local population, attacked the administrative post at Chai in Cabo Delgado province. The monsoon season and the poor infrastructure and rough terrain of Northern Mozambique posed severe difficulties for colonial troops pursuing the guerrillas. After the initial attacks were confined to the north, FRELIMO began to mount attacks in Central Mozambique too, around Tete and Niassa. Guerrilla actions by FRELIMO were typically mounted by units no larger than 15 men, and widely dispersed in order to prevent the Portuguese from concentrating their forces. These widespread actions were largely able to be accomplished utilising the Ruvuma and Lugenda rivers to redeploy and supply units throughout the north. Lake Malawi, however, was largely off-limits due to the hostility of Rhodesia-Nyasaland to the Mozambique self-determination struggle [184]. In 1965, with popular support for FRELIMO growing and a successful recruiting drive, FRELIMO strike teams began to increase in size. The insurgents also began to lay landmines behind them as they withdrew after strikes, pulling pursuing forces into minefields. This had the impact of increasing casualty rates as well as demoralising the colonial forces.

By 1967, FRELIMO had de facto control of vast swathes of the north, comprising one-fifth of the total landmass of Mozambique and containing one-seventh of the population. Mondlane began looking for more foreign support, the success of the guerrilla movement now requiring more guns, ammunition and training for new recruits. He secured support from the Soviets, Chinese and East Germans, who predominantly sent WWII-vintage weapons, along with some tactical rocket batteries. One of the Portuguese responses to the growing insurgency was an increase in rural development, seeking to turn local support in their favour by improving infrastructure. The most notable of these infrastructure projects was the Cahora Bossa Dam, construction of which began in 1969. Aside from its practical functions, the dam was also intended to symbolise the permanence of the Portuguese colonial project. Three thousand troops and a million landmines were sent to defend the construction site. This proved sufficient to defend the project from multiple attacks from FRELIMO forces, although the guerrillas had occasional success at interdicting supply convoys, delaying construction somewhat.

In 1969, Mondlane was killed by a mailbomb sent to his office in Dar Es Salaam. The assassination is believed to have been orchestrated by Aginter Press, the Portuguese branch of the Gladio system of stay-behind networks in Western Europe. Lazaro Kavandame, the FRELIMO commander of Cabo Delgado province who had been openly critical of Mondlane, was suspected to be involved. He handed himself in to the Portuguese in order to prevent execution by his former allies. After a short period of internal discord, Samora Machel would be appointed the new president of the organisation. Under Machel, FRELIMO would continue its leftward political shift at an accelerated pace. A change in the command situation of the Portuguese forces, with General Kaúlza de Arriaga taking over from General António Augusto dos Santos in 1970 marked a profound shift in Portuguese strategy. de Arriaga had little faith in the effectiveness of African soldiers under colonial command, and as such largely replaced them with regular Portuguese troops from the metropole, with small numbers of native auxiliaries. This approach didn't prove any more effective than dos Santos' tactics, and under pressure from his subordinates, most notably his second-in-command General Francisco da Costa Gomes, authorised the use of native flecha units. Costa Gomes believed that the indigenisation of the Portuguese colonial army was necessary in order to win the "hearts and minds" of the indigenous population, and would help limit the issues of adaption to local conditions which many draftees from the metropole experienced. During the early 1970s, FRELIMO's combat actions also spread to urban centres, further broadening the scope of the anticolonial insurgency. June 1970 saw the most major offensive of the war, Operation Gordian Knot. Involving some 35,000 Portuguese troops, the seven-month operation targeted cross-border infiltration routes and insurgent bases in the north. To this day, the effectiveness of Operation Gordian Knot is a matter of debate. At the time it was seen as a failure, with the monsoon season and a lack of effective cooperation between ground and air forces seeing the Operation fall short of its expected results. Nevertheless, it did severely weaken the ability of FRELIMO to hold many territories long-term and significantly weakened the offensive potency of FRELIMO guerrillas. On December 16, 1972, the massacre of the entire civilian population of the village of Wiriyamu by Portuguese forces started to shift public opinion in the metropole about the war in Mozambique. By this point, the various wars in the Portuguese colonies were taking up 40% of Portuguese GDP and as such was applying major stress to the already (by Western European standards) weak Portuguese economy. Whilst FRELIMO forces also sometimes engaged in brutality against native villages, none of their atrocities compared to the slaughter at Wiriyamu.

By 1973 the Portuguese were attempting to sever FRELIMO from their local support networks by establishing resettlement villages. FRELIMO had adopted a completely opposite policy towards Portuguese settlers. Whilst Mondlane had promoted a policy of mercy for European settlers, Machel had a far harsher views towards the white population. Despite the fact that the Portuguese were still in control of the majority of Mozambican territory, the difficult situation for the Portuguese was summed up by comments from a Portuguese journalist: "In Mozambique we say there are three wars: the war against FRELIMO, the war between the army and the secret police, and between the central government [and the settlers]". The spiralling situation in the colonial possessions contributed to the unrest in the Portuguese home territories which would eventually result in the collapse of the Portuguese colonial empire on mainland Africa.

===

[183] Historically, this organisation was founded in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. ITTL, where Tangyanika and Zanzibar are separate nations, this organisation was founded instead in Zanzibar.

[184] IOTL, FRELIMO was able to utilise Lake Malawi for movement and resupply due to Malawi's support of the movement. ITTL, Malawi (Nyasaland) is still a part of the Central African Federation.

Recognising a higher degree of unrest amongst the native traditional rulers of Angola, in 1951 the Portuguese government changed the status of the territory, from a formal "colony" of Lisbon into a "overseas province". Despite this shift, governance of Angola remained under the control of a white-operated government bureaucracy, with only local input required from traditional native leaders. This was seen as a particular affront in the northwest of Angola, in the territories that had once made up the Kingdom of Kongo. In 1954, the União dos Povos do Norte de Angola (Union of Peoples of Northern Angola, UPA) was established under the leadership of Holden Roberto, a descendant of Bakongo royalty. Despite the name, the UPA was almost entirely comprised of Bakongo people, seeking to resurrect their independence from Portugal, with little consideration for the other Angolan peoples. Two years later, the Angolan Communist Party and the Party of the United Struggle for Africans in Angola merged to form the Movimento Popular de Liberação de Angola (People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola, MPLA). The MPLA drew its ranks primarily from Luanda's urban intelligentsia and the Ambundu people who lived on territories centred around Luanda and the Cuanza river. These Ambundu were the historical heirs to the legacy of the Ndongo Kingdom, but the MPLA promoted a message of unity between the various peoples of Angola, including (at least rhetorically) a willingness to accept Angolans of European descent into their organisation.

On January 3, 1961, the tensions that were building up in Angola came to a head. Agricultural workers employed by Belgian-Portuguese cotton plantation operation Cotonang staged a protest in Baixa de Cassanje demanding an improvement in working conditions. The demonstrators would go as far as beating Portuguese traders that were onsite. Spontaneous shows of support broke out in nearby settlements, and was suppressed by a Portuguese terror-bombing campaign which targeted twenty surrounding villages. The MPLA claimed that the death toll was 10,000, and while this is most likely an exaggeration, historical estimates range between 400 and 7,000 dead native Angolans. A couple of days later, the Portuguese liner Santa Maria was seized by operatives of the Iberian Revolutionary Liberation Directorate (DRIL) operating under the command of Henrique Galvão, a military officer and general secretary of DRIL's Portuguese branch. Intending to establish an opposition Portuguese government in Angola, he was instead forced to redirect to Brazil, liberating the crews and passengers in exchange for political asylum. Between the fourth and tenth of January, a number of armed incidents took place in Luanda. Whilst the exact details are unclear, with several parties having given contradictory accounts, there were a number of attacks on police by black militants armed with machetes, followed by a police response in black-majority neighbourhoods in the city. Some claim that the police response was also accompanied by lynchmobs of white settlers, whereas others claim this to be a fabrication intended to strain relations between the communities. Responsibility for the initial attacks was claimed by the MPLA, although the Portuguese secret police claimed that a local nationalist priest was behind the incident.

On March 15, the UPA staged a major uprising in the Bakongo territories; farmers and coffee plantation workers took up arms and what ensued was a slaughter. A thousand white settlers were killed, along with thousands more native workers, mostly ethnic Ovimbundu people from the central highlands, who were in the north as contract labourers. Arson attacks were carried out on police stations, plantations, ferries and many other targets. Journalists published images of raped and mutilated white settlers in newspapers in the metropole and throughout the rest of the colony, manufacturing consent for a heavy-handed response from the military. Later testimony also claimed that some UPA forces engaged in cannibalism of killed Portuguese soldiers. Whilst there were plenty instances of farms and smaller hamlets being completely overrun, many of the Portuguese settlers in the area retreated into regional hubs and entrenched themselves, forming militias in order to rebuff the disorganised assaults from the untrained insurrectionists. These militias would afterwards be organised into the Organização Provincial de Voluntários de Defesa Civil (OPVDC), a paramilitary force tasked with settlement defense and auxiliary support for the Portuguese regular military. This caught Roberto and the rest of the UPA leadership by surprise, as they expected the white settler population of the region to flee in panic. It is worth noting that this revolt wasn't simply an anti-colonial rebellion; it was an attempt by the UPA leadership to reassert political and economic authority over the northern regions. Attacking Ovimbundu contract workers with the same savagery as white colonists, the UPA insurrectionists sought to create conditions of Bakongo supremacy in the former Kongo territories.

On July 10, after having reoccupied some of the smaller northern towns, the Portuguese military commenced Operação Viriato to conquer the town of Nambuangongo, which had become the UPA headquarters. Converging on the town along three axes, the Portuguese occupied the town a month after the commencement of the operation. The Portuguese also captured the village of Quipedro to interdict the UPA's line of retreat from Nambuangongo. The attack on Quipedro was achieved through an airborne assault which took the revolters by suprise and resulted in the capture of the village without effective resistance. Attempting to provide a carrot to go along with the stick, on August 6 the Novo Estado adopted the Statute of the Portuguese Indigenous of the Provinces of Guinea, Angola & Mozambique, giving all indigenes equal citizenship rights and obligations as ethnic Portuguese. On 16th September, the UPA's last base in northern Angola, Pedra Verde, was captured by Portuguese troops in Operação Esmeralda. The UPA had no choice but to flee over the border to Congo, the Portuguese having killed 20,000 in this suppression campaign. Despite some misgivings about the UPA's refusal to adopt pan-Africanist ideology, Lumumba's government nevertheless allowed the UPA to establish bases on their side of the border in order to harass the Portuguese colonialists. The 9th October also saw a small incident that would have major consequences for the future of Angola: a UPA patrol took 21 MPLA personnel prisoner and executed them, precluding any chance of cooperation between the two resistance groups. After fleeing to Congo, the UPA merged with the Democratic Party of Angola and renamed itself the Frente Nacional de Libertação de Angola (FNLA).

February 1962 saw the establishment of the Angolan Revolutionary Government in Exile (GRAE) in Congo, with Holden Roberto as its President and Jonas Savimbi as Foreign Minister. Later that same year, an MPLA congress replaced General-Secretary Viriato da Cruz with Agostinho Neto. Da Cruz and Neto had clashed on several occasions, particularly on the subject of the racial composition of the party. Da Cruz, despite being of mixed ancestry himself, wanted to reserve a number of party seats for black African members. Whilst there was some diversity amongst MPLA ranks, the leadership, being drawn from the Luanda intelligentsia, was predominantly mestiço. In the enclave of Cabinda in the north, 1963 saw the merging of three nationalist groups into the Front for the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda (FLEC) which began low-level engagements with Portuguese security forces, mostly police. Their cause was bolstered diplomatically by the declaration of Cabinda as an independent state by the Organisation of African Unity. Nevertheless, they would pose very little threat to the Portuguese military. Dialogue did however, commence between the government of Congo and the FLEC.

In 1964, frustrated by Holden Roberto's unwillingness to spread the guerrilla operations of the FNLA outside of the Bakongo territories, his insistence on refusing support from the Soviet Union and China, and the lack of a political programme, Jonas Savimbi left the FNLA and relocated to China with some supporters. Meanwhile, the MPLA started slowly building up its strength, receiving armaments from the Soviet Union and the German Democratic Republic. Relative to the more unified and effective FARP in Guinea-Bissau, the MPLA received only older surplus weaponry, particularly from the GDR. Whereas the image of the AK-47-toting militant may have been associated with the various national liberation movements of the 1960s and 1970s, it was far more common in Angola to see MPLA insurgents armed with old Mauser bolt-action rifles. In May of 1966, Daniel Chipenda of the MPLA established a new area of operations, the Eastern Front, almost doubling the MPLA's reach. Jonas Savimbi, returning from China, establishing the União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola, UNITA) in a conference at Moxico province in the southeast on March 13. UNITA would commence armed operations on Christmas Day, derailing trains passing along the Benguela railway at Teixiera de Sousa, on the border with Rhodesia-Nyasaland. Immediately UNITA had an impact, with their forces being much better-led and trained than either FNLA or MPLA guerrillas. UNITA operations along this railway would especially frustrate the leadership of the neighbouring white-ruled Central African Federation, which relied on the Benguela railway to bring its copper exports to a port where it could reach foreign markets. The following year, UNITA would be successful in two more major derailings along this line, although increasing pressure from the Portuguese military in the region caused Savimbi to himself relocate to Cairo. Savimbi also established some contacts with Portuguese intelligence, where he would pass on information about the location of MPLA bases in order to undermine his pro-Soviet rivals.

May of 1968 saw FNLA fighters cross for the first time into Eastern Angola. By this time, it was clear that Eastern Angola would become an important battlefield, allowing any group which controlled this region to monopolise the control of blood diamonds in this area, as well as to interfere with the ability of their rival rebel groups to get support from their neighbours such as Congo and Rhodesia-Nyasaland. As may be expected by an organisation that was so strongly tied to one particular ethnic group, the FNLA operations in Eastern Angola were typically brutal, aimed at control of diamond production and with little care for the wellbeing of the local populations. In October, the Portuguese mounted Operação Vitória to root out MPLA bases in the east. Portuguese forces also managed to capture important documents that revealed the position of various other MPLA troops positions. For their part, the MPLA did also discreetly pass on the location of FNLA patrols to Portuguese troops. Despite the continued operation of the rebel forces, by this point in the war the momentum was clearly in the favour of the Portuguese. All separatist forces were secretly sending intel on their rivals to the Portuguese, and the colonial forces were also increasingly utilising the most modern counterinsurgency techniques. Whilst elements of the Portuguese command still distrusted African troops, there was an increase in recruitment of them, as other notable figures in the army such as Spínola and Francisco da Costa Gomes promoted their use, claiming that they're cheaper than European troops, more accustomed to the local climate and terrain and better able to develop relationships with local communities. The PIDE even established its own elite paramilitary force, the Flechas (Portuguese for Arrows) comprised predominantly of Khoisan bushmen. Specialising in covert operations, close quarters combat, desert warfare, jungle warfare, and virtually all other skillsets that would later come to be known as "black operations", these forces didn't operate under the command of the army but where entirely an instrument of the Portuguese secret police. They were particularly feared due to their brutality and their ability to sudden strike with no warning. Some of the more superstitous rebels even believed them to have supernatural powers garnered from black magic, a reputation that the PIDE didn't try to dispel. The regular military established Battle Group Sirocco, a highly mobile task force assisted by a dedicated air cavalry arm that would engage in rapid response operations throughout Eastern Angola. Whilst at the onset of the colonial war, the Portuguese forces had somewhat struggled to find their footing due to their initial composition as a component of overall NATO, and later LDO command, by the late 1960s they were well-versed in irregular combat in difficult terrain. In response, the rebel forces were forced to begin former larger squadrons in order to have any combat effectiveness at all. The MPLA began operating squadrons of 100 to 145 militants rather than the old platoon-sized cells. Armed with 60mm and 81mm mortars provided by the USSR, they were limited to attacks on small outposts and patrols, but were unable to make any real notable headway. To make matters worse for the MPLA, in 1972 South African Defense Force (SADF) units began engaging them in Moxico province with Portuguese consent. Operating through Rhodesia-Nyasaland, the SADF forces were there to take revenge for MPLA support for the South-West African People's Organisation (SWAPO) which operated in the territory of South-West Africa, which South Africa administered initially under trusteeship but had de facto annexed despite condemnation from the United Nations. The SADF campaign forced the MPLA out of Moxico province. The combined Portuguese and South African offensives in the east effectively pushed the MPLA out of that territory. This turn of events precipitated infighting amongst the leadership of the MPLA. Neto and 800 of his fighters retreated into Congo, whilst Chipenda began secret negotiations with the Soviets to shift their support away from Neto.

On 17th March, 1,000 FNLA fighters mutiny at camps in Kinkuzu within Congolese territory, but were suppressed by Congolese troops on behalf of FNLA leadership. In 1973, Daniel Chipenda left the MPLA, and forming a rival group, the Revolta do Leste (Eastern Revolt) with 1500 followers and covert Soviet and South African support (motivated by the desire to further undermine the MPLA). Despite Soviet support, he was privately wary of Soviet influence, and strongly opposed to the mestiço leadership of the MPLA. Later that year, Neto was invited to Moscow and told that Chipenda planned to assassinate him. These events have raised some speculation that Soviet support for the Eastern Revolt was part of a KGB operation seeking to maintain MPLA integrity by passing along information about rivals to Neto. China also shifted aid away from MPLA, sponsoring UNITA but also the FNLA, presumably in order to undermine the pro-Soviet MPLA. 1973 saw another split in MPLA, with founder Mário Pinto de Andrade clashing with Neto and establishing their own group, the Revolta Activa. Neto managed to reassert his authority soon thereafter, with Pinto de Andrade fleeing to Guinea-Bissau. The Revolta do Leste merged with FNLA. The internecine fighting amongst the rebel groups would have almost certainly lead to eventual victory for the Portuguese colonial forces, but events in the metropole changed the destiny of Angola and left the nation's future in the hands of these warring factions.

Disparities between the settler population and indigenous Africans was even more severe in Mozambique. Under the Estado Novo regime, indigenous farmer were compelled to produce cash crops such as cotton for export, forcing them in many instances to forage or to buy food at raised prices from ethnic Portuguese farmers, whilst selling their cash crops at reduced rates, despite living on arable land that would otherwise be able to sustain their nutritional needs without issue. Over a quarter of a million native Mozambicans also worked in Rhodesia-Nyasaland and South Africa (in the latter, they comprised over 3/10s of underground miners) and were heavily taxed by the Mozambique colonial administration for their remittances. In 1950, out of a total indigenous Mozambican population of over 5 and a half million, a mere 4,000 or so natives possessed voting rights. Rates of ethnic intermixing were also the lowest in Mozambique of all the Portuguese colonies, by 1960 only numbering around 31,000. This number also underscores the vast degree of segregation between native and settler communities, which resembled the conditions in neighbouring South Africa more so than in Angola or Cabo Verde. The Liberation Front of Mozambique (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique, FRELIMO) was established in 1962 in Zanzibar [183] under the leadership of Eduardo Mondlane, a historian and sociologist who had briefly worked as a professor at New York's Syracuse University. FRELIMO had been created as a union of a number of smaller, disparate independence movements which had sprouted up, inspired by the pan-African liberation movements and the newfound independence of several states which had once been under British, French and Belgian rule. FRELIMO was initially completely reliant on support from friendly regimes, as the Estado Novo's ruthless intelligence apparatus had forced the Mozambique independence movement into exile. FRELIMO guerrillas were allowed to train (with Chinese assistance) and operate from bases in southern Tangyanika. With only around 7,000 fighters, a conventional victory against the Portuguese was a hopeless proposition; but a protracted guerrilla war had potential to force Lisbon to the negotiating table.

1964 saw the first FRELIMO attacks in Mozambique, negotiations with the Portuguese having proven fruitless. FRELIMO guerrillas, with assistance from the local population, attacked the administrative post at Chai in Cabo Delgado province. The monsoon season and the poor infrastructure and rough terrain of Northern Mozambique posed severe difficulties for colonial troops pursuing the guerrillas. After the initial attacks were confined to the north, FRELIMO began to mount attacks in Central Mozambique too, around Tete and Niassa. Guerrilla actions by FRELIMO were typically mounted by units no larger than 15 men, and widely dispersed in order to prevent the Portuguese from concentrating their forces. These widespread actions were largely able to be accomplished utilising the Ruvuma and Lugenda rivers to redeploy and supply units throughout the north. Lake Malawi, however, was largely off-limits due to the hostility of Rhodesia-Nyasaland to the Mozambique self-determination struggle [184]. In 1965, with popular support for FRELIMO growing and a successful recruiting drive, FRELIMO strike teams began to increase in size. The insurgents also began to lay landmines behind them as they withdrew after strikes, pulling pursuing forces into minefields. This had the impact of increasing casualty rates as well as demoralising the colonial forces.

By 1967, FRELIMO had de facto control of vast swathes of the north, comprising one-fifth of the total landmass of Mozambique and containing one-seventh of the population. Mondlane began looking for more foreign support, the success of the guerrilla movement now requiring more guns, ammunition and training for new recruits. He secured support from the Soviets, Chinese and East Germans, who predominantly sent WWII-vintage weapons, along with some tactical rocket batteries. One of the Portuguese responses to the growing insurgency was an increase in rural development, seeking to turn local support in their favour by improving infrastructure. The most notable of these infrastructure projects was the Cahora Bossa Dam, construction of which began in 1969. Aside from its practical functions, the dam was also intended to symbolise the permanence of the Portuguese colonial project. Three thousand troops and a million landmines were sent to defend the construction site. This proved sufficient to defend the project from multiple attacks from FRELIMO forces, although the guerrillas had occasional success at interdicting supply convoys, delaying construction somewhat.

In 1969, Mondlane was killed by a mailbomb sent to his office in Dar Es Salaam. The assassination is believed to have been orchestrated by Aginter Press, the Portuguese branch of the Gladio system of stay-behind networks in Western Europe. Lazaro Kavandame, the FRELIMO commander of Cabo Delgado province who had been openly critical of Mondlane, was suspected to be involved. He handed himself in to the Portuguese in order to prevent execution by his former allies. After a short period of internal discord, Samora Machel would be appointed the new president of the organisation. Under Machel, FRELIMO would continue its leftward political shift at an accelerated pace. A change in the command situation of the Portuguese forces, with General Kaúlza de Arriaga taking over from General António Augusto dos Santos in 1970 marked a profound shift in Portuguese strategy. de Arriaga had little faith in the effectiveness of African soldiers under colonial command, and as such largely replaced them with regular Portuguese troops from the metropole, with small numbers of native auxiliaries. This approach didn't prove any more effective than dos Santos' tactics, and under pressure from his subordinates, most notably his second-in-command General Francisco da Costa Gomes, authorised the use of native flecha units. Costa Gomes believed that the indigenisation of the Portuguese colonial army was necessary in order to win the "hearts and minds" of the indigenous population, and would help limit the issues of adaption to local conditions which many draftees from the metropole experienced. During the early 1970s, FRELIMO's combat actions also spread to urban centres, further broadening the scope of the anticolonial insurgency. June 1970 saw the most major offensive of the war, Operation Gordian Knot. Involving some 35,000 Portuguese troops, the seven-month operation targeted cross-border infiltration routes and insurgent bases in the north. To this day, the effectiveness of Operation Gordian Knot is a matter of debate. At the time it was seen as a failure, with the monsoon season and a lack of effective cooperation between ground and air forces seeing the Operation fall short of its expected results. Nevertheless, it did severely weaken the ability of FRELIMO to hold many territories long-term and significantly weakened the offensive potency of FRELIMO guerrillas. On December 16, 1972, the massacre of the entire civilian population of the village of Wiriyamu by Portuguese forces started to shift public opinion in the metropole about the war in Mozambique. By this point, the various wars in the Portuguese colonies were taking up 40% of Portuguese GDP and as such was applying major stress to the already (by Western European standards) weak Portuguese economy. Whilst FRELIMO forces also sometimes engaged in brutality against native villages, none of their atrocities compared to the slaughter at Wiriyamu.

By 1973 the Portuguese were attempting to sever FRELIMO from their local support networks by establishing resettlement villages. FRELIMO had adopted a completely opposite policy towards Portuguese settlers. Whilst Mondlane had promoted a policy of mercy for European settlers, Machel had a far harsher views towards the white population. Despite the fact that the Portuguese were still in control of the majority of Mozambican territory, the difficult situation for the Portuguese was summed up by comments from a Portuguese journalist: "In Mozambique we say there are three wars: the war against FRELIMO, the war between the army and the secret police, and between the central government [and the settlers]". The spiralling situation in the colonial possessions contributed to the unrest in the Portuguese home territories which would eventually result in the collapse of the Portuguese colonial empire on mainland Africa.

===

[183] Historically, this organisation was founded in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. ITTL, where Tangyanika and Zanzibar are separate nations, this organisation was founded instead in Zanzibar.

[184] IOTL, FRELIMO was able to utilise Lake Malawi for movement and resupply due to Malawi's support of the movement. ITTL, Malawi (Nyasaland) is still a part of the Central African Federation.

As always, I'm glad seeing you uploading again, hopefully Angola and Mozambique manage to win their independence and further surround South Africa with anti Apartheid regimes.

Chapter 82: Quem Brinca com Fogo, Quiema-se - Portugal's Colonial Wars and their Consequences (Part 3)

With a lack of economic growth at home; expensive commitments to conflicts in the far-flung colonial empire; and growing discontent at the conscription of young men from the middle and lower classes of the population to fight in tropical backwaters, the Estado Novo regime was buckling under the stresses of multiple concurrent crises. Since 1968, when Salazar had suffered a stroke that left him incapable of governing, Marcelo Caetano had taken the post of Prime Minister at an unenviable time. Western Europe was in a time of transition; democracy had been snuffed out in France, uncertainty loomed about the future of the government of aging Francisco Franco in neighbouring Spain, and plans of an abortive coup by the Italian elite in the piano solo scandal had deepened the ever present divides in that country. Caetano was a loyalist of Salazar, sure, but he hoped that he would be able to steer Portugal towards sustained economic growth. The key to this, in his mind, was the effective exploitation of the underdeveloped resources in the African colonies, most notably Angola. Offshore oil reserves could, in theory, be exploited to achieve energy independence, or something approaching it, and prevent future oil shocks (like the ones that briefly shook Western economies during the fall of the Saudi kingdom and the nationalisation of ARAMCO) from retarding Portuguese economic growth. With this rational, it was never optional that Portugal retain control of Angola and Mozambique, no matter the cost. There were political reasons for maintaining control of the colonies also; under Salazar a corporatist economic policy had been pursued. This left many major industries in the hands of a few well-connected and very wealthy families. Much of this industry was fuelled by the sale or use of raw materials from the colonies. Cash crops such as bananas, cashews, coconuts and specialist timber were produced in the African colonies, as well as industrially-useful metals, diamonds and even cement. The loss of these resources would disproportionately impact the large conglomerates, and anger the well-off and politically-connected elites. They could prove a dangerous enemy indeed, and had in the past been amongst the most ardent supporters of the Estado Novo. The military were another pillar of the Estado Novo which couldn't tolerate failure in Africa. As is typical of militaries, the esteem of their upper echelons was largely dependent on military success. The nationalistic tendencies of the old guard at the top, as well as their anti-communist paranoia, made them a steadfast supporter of the Estado Novo in the past, but any admission of defeat in Africa would quickly turn them against whoever held power. It is for these reasons that despite some softening of his predecessor's policies, such as the introduction of a monthly pension to rural labourers, loosening of restrictions on the press and the authorisation of the first democratic labour union since the 1920s, Caetano committed, by 1974, a full 40% of the national budget to the colonial conflagrations. As the country had become politically polarised, particularly after the Wiriyamu Massacre, thousands of left-wing and anti-war Portuguese fled abroad, primarily to the United States, establishing a notable diaspora centred around Connecticut [185].

Whilst the brain drain caused by the exodus of anti-government middle class Portuguese wasn't ideal, a much more serious threat to the regime emerged: the Movimento das Forças Armadas (Armed Forces Movement; MFA). The MFA was an organisation of junior officers who had been alienated by the Caetano government. There were a couple of major points of contention with government policy; whilst many were disillusioned with the overall policies of the regime, the major catalyst for the establishment of the MFA was a change to military recruitment policy, where local militia officers in the colonies were given the same status as military academy graduates when it came to promotions. This policy had been adopted by the Novo Estado regime on the advice of the leaders of Rhodesia-Nyasaland, as a method to reduce costs for the military. Resented by the academy graduates for obvious careerist reasons, it was also risky in that it could result in an officer corps without the theoretical and technical knowledge required should a wider war break out in Europe against the Warsaw Pact. The principal aims of the MFA was a retreat from the losing wars in Africa, the introduction of free elections and the disestablishment of the secret police, the PIDE.